What Chinese company Zhenhua Data will do with data of 35,000 Aussies

The Chinese government is actively spying on thousands of Australians. Here’s how your private information could be used for terrifying means.

You – the internet user – have become the front line in a battle for hearts, minds and political advantage. And your personal details are the weapons in an international struggle for power.

News that the Chinese company Zhenhua Data had profiled more than 35,000 Australians among a database of some 2.5 million comes as no surprise to digital privacy and social media analysts.

Information is power.

And that information is easy to steal.

Western corporations have been data-scraping the internet for decades to give them a marketing edge over their competitors. There’s little wonder that political entities have begun doing the same, argues Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) analyst Michael Shoebridge.

“The consequences of Google or Facebook having masses of data about you are serious and rightly a topic of public debate and potential further regulation,” Shoebridge says.

“But they are quite different to the consequences of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its technology companies having huge amounts of personal information about you and your family.”

RELATED: 35,000 Aussies are being spied on by China

Zhenhua is just one of several Chinese state-run businesses determined to learn everything it can about you. Even if they don’t have a use for that information – yet.

It means Beijing can sift through thousands of candidates for ‘back doors’ into political, academic and corporate arenas. It’s about finding the weakest links to leverage to their advantage, he argues.

“Coercive economics and pressure on governments and companies to say and do what Beijing wants is one clear use,” Shoebridge said. “Another is being able to influence political debates and even national decision-making.”

HOME FRONT ASSAULT

Tech giants such as Facebook and Google boast to advertising agencies and lobby groups that they harvest thousands of ‘data points’ from each of their billions of users.

It’s surveillance for profit. It’s sold for targeted advertising and market research.

International laws – including Australian privacy provisions – make it illegal to store identifiable data portraits of individuals. But researchers warn there’s growing evidence such datasets are being aggregated for psychological profiling and attitude “nudging”.

Your habits, weaknesses, preferences, biases – even health – can be leveraged through the masses of data collected on you.

“The CCP’s methods are not that different from what we see in the global advertising industry,” ASPI researcher Samantha Hoffman recently told the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“But instead of trying to sell a product, the CCP is trying to exert authoritarian control. It’s using capitalism as a vehicle to access data that can help it disrupt democratic processes and create a more favourable global environment for its power.”

RELATED: Big Brother is watching Australian influencers

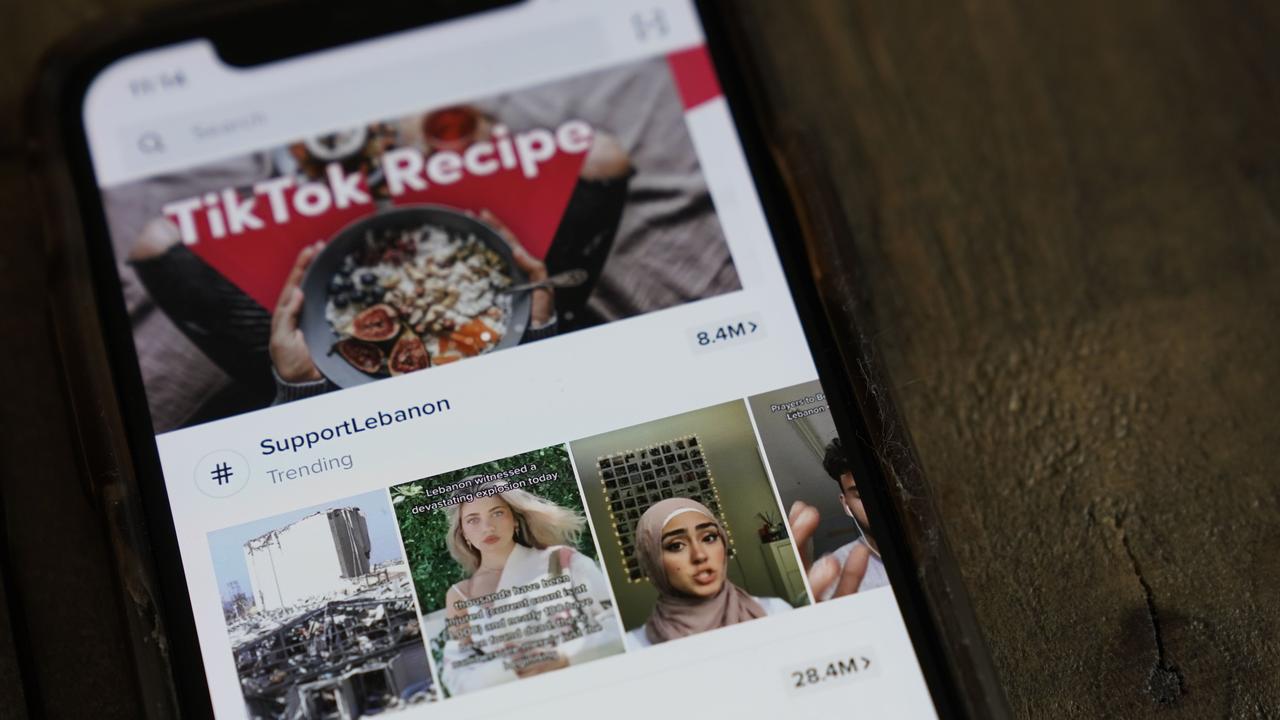

It’s one of the reasons why social media platform TikTok has attracted so much scrutiny in recent months.

“TikTok is a good example of a seemingly benign app that can give the CCP a lot of useful data,” she said.

“You wouldn’t think of a social media app that is used by a lot of children around the world as being inherently problematic for political reasons. But the sentiment data from an app like TikTok can be used to understand how people are influenced and how they think.”

SURVEILLANCE SCORE

Attached to every name in the controversial Zhenhua Database is a number. It’s meaning is unknown.

But it’s not unique.

The Chinese Communist Party under its autocratic chairman Xi Jinping has begun imposing an intensive surveillance system on its 1.4 billion citizens. Its effects are already being seen.

Credit card details. Facial-recognition surveillance cameras. Social media posts. Web activity. Reports from local political commissars. All are fed into a national artificial intelligence system that algorithmically determines whether you’ve been naughty or nice.

RELATED: Sick reason TikTok video went viral

Chinese citizens don’t get told their resulting ‘Social Score’. Their only clue comes when they go to book a train ride to the coast for a holiday. Or apply for a promotion. The Communist Party’s computer system will simply say yes – or no.

So how do such AI assessments apply internationally?

“It’s not clear how individuals are being targeted,” says assistant professor Bruce Baer Arnold of the University of Canberra School of Law.

“The profiling might be systematic. It might instead be conducted on the basis of a specific industry, academic discipline, public prominence or perceived political influence.”

What value would the Communist Party gain from gathering and scoring personal profiles on international government, corporate, media, entertainers and social media influencers?

Shoebridge argues they can help identify who might be willing or susceptible to co-operation.

“Large datasets like this can boost conventional espionage operations significantly,” Shoebridge writes.

“They give levers to obtain co-operation willingly or unwillingly. When those levers include not just personal foibles and vulnerabilities, but information about a target’s children, relatives or friends, it starts to look uglier, even malign.”

INFORMATION WARS

Personal dirt equals power. And that can be applied to politicians, media and personalities to significant effect.

“Think about telling a key participant in a high-level government decision that if they don’t do what you want, you’ll reveal a distressing and compromising thing about one of their children to the world,” Shoebridge writes.

“Think about enticing influential people to do what you want by paying off the large legal or medical bills you know they have because of the data you hold about them.”

Unlike open democracies, China’s rigidly controlled social and news media systems are solely designed to support the Communist Party.

There’s little chance any Chinese citizen will get to read about Xi Jinping’s billion-dollar family fortune, for example. Or a ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomat’s embarrassing foot-fetish “like” on Twitter (a service any of his citizens could be jailed for accessing anyway).

The Australian federal government recently announced plans to establish a group designed to tackle disinformation campaigns being directed at social and traditional media, and key public figures.

Foreign Minister Marise Payne went so far as to accuse China and Russia of attempting to “undermine liberal democracy” by spreading disinformation to manipulate social media debate.

“Where we see disinformation, whether it’s here, whether it’s in the Pacific, whether it’s in Southeast Asia, where it affects our region’s interests and our values, then we will be shining a light on it,” Payne said in June.

She highlighted how such false narratives were given credibility when repeated by trusted sources – such as friends, family, and community leaders.

POLITICAL TARGETS

What we’ve seen of Zhenhua’s intercepted dataset seems a relatively basic assembly of names, birthdays, addresses, photographs, political ties and relatives.

But ASPI’s recent Engineering Global Consent report highlights far more extensive digital data gathering activities of another Chinese technology firm, GTCOM.

It’s controlled by China’s Central Propaganda Department and claims to harvest 10 terabytes of data from across the world every day from the likes of Twitter, Facebook, WeChat, public chat forums, blogs and services pages.

“The company describes its work as contributing directly to China’s national security, including military intelligence and propaganda,” Hoffman says.

“The Party talks about its intent to shape global public opinion in order to protect and expand its own political power. At the same time, Chinese tech companies collect data in support of such efforts.”

Military analysts often refer to China’s concept of “Three Warfares”. It argues warfare is not just about militaries fighting. It’s also about controlling the political, economic and psychological processes of opponents.

“The Chinese government and its corporate assistants will be using the insights from this giant data pool to obtain political, commercial, strategic and military advantage for the Chinese government and Chinese companies right now, including in ways that break other countries’ laws and rules,” Shoebridge says.

“The insights from these datasets are valuable for powering foreign interference by Chinese actors in other states and societies. They are the fuel for Chinese state entities’ covert and corrupting activities.”

LAST CHANCE?

Subliminal advertising flickers of the 1970s. The Australia Card privacy uproar of the 1980s. The explosion of closed-circuit surveillance systems in the 1990s.

All were met with public outcry and subsequent strict government regulation.

Not so the all-pervasive prying of international social media and internet search giants. Nor the obsessive data collection of corporations and governments.

“Citizens of liberal democracies are rightly concerned with how tech companies abuse their data, but at least in liberal democracies there are growing restraints on how data is used,” says Hoffman.

“In China, where the party-state literally says that the purpose of the law is to “strengthen and improve the Party’s leadership,” technology is deployed to extend the political power of the party-state.”

China was implicated in the recent theft of Australian National University records. The university concedes this could have been going on for some 19 years.

Earlier this year, the NSW Government admitted personal details on 200,000 citizens were stolen from its archives.

But democratic governments are addicted to data.

“Pervasive surveillance is now a standard feature of all major governments, which often rely on surveillance-for-profit companies,” Arnold writes. “Governments in the West buy services from big data analytic companies such as Palantir.”

What is needed, he says, is a renewed focus on data resilience.

“One way is to require government agencies and businesses to safeguard their databases. That hasn’t been the case with the NSW government, Commonwealth governments, Facebook, dating services and major hospitals.”

Shoebridge warns a battle is also underway to secure the future of the internet architecture.

“Australia and other open democracies need to pile in on the new internet standards and governance if we aren’t to get a redesigned internet that’s even easier to use covertly and corruptly for authoritarian purposes than the one we have now,” he says.

Hoffman adds it’s also a matter of asserting the rule of law, and democratic principles.

“Liberal democratic governments must bolster data privacy laws and rethink how to manage propaganda from both foreign and domestic sources in the digital age — but without compromising democratic values along the way. To do that, they must be clear about what their values are and why they differ from those of authoritarian regimes.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel