ISIS death-cult tells Aussie supporters how to sidestep government internet scrutiny

AUSTRALIAN terror supporters have been handed explicit instructions on how to avoid leaving a digital fingerprint.

AUSTRALIAN terror supporters have been handed explicit instructions on how to avoid leaving a digital fingerprint.

Days after the Federal Government passed contentious new laws, allowing security agencies to access two years of an individual’s metadata, News Corp Australia has sighted documents on recommended internet behaviours for “pro-IS sympathisers”.

The 60 text files, uploaded in Arabic by a Twitter user which News Corp has verified but chosen not to name for legal reasons, contain instructions on how to dodge online government security apparatuses monitoring people linked to the death cult.

“It’s almost like a stay safe online guide for jihadists,” said Lee Mansfield, the practising manager for Cyber Security for Thales Group.

“These are standard things that have always been a problem for organisations trying to get information.”

Islamic State supporters and fighters are encouraged in the documents to use virtual private networks, randomise their IP address with browsers like TOR and use secure encryption strategies when sending messages.

They are also shown how to attack and shut down websites.

Counter terrorism experts say the information is a 101-framework for extremists to avoid detection.

“It’s (the documents) just further evidence of both the scale of the challenge in trying to address this stuff and the technical sophistication of the people we are trying to interdict,” said terrorism and national security lecturer Levi West, from Charles Sturt University.

Dr Suelette Dreyfus, a research fellow in computing and information systems at the University of Melbourne, described the guide as ‘what you’d learn in a basic intro training course on computer security’.

“It does give reasonable coverage to the basics however (ie it spells them out fairly clearly and covers ground. It’s like a Wikipedia of attacks, only maybe slightly more detailed),” Dr Dreyfus said.

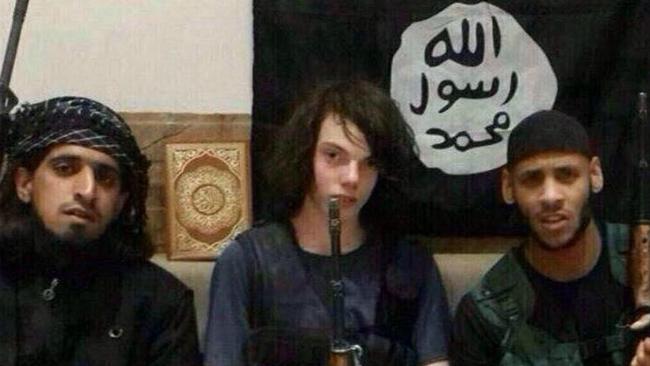

The number of Australians believed to be currently fighting with ISIS is 92. More than 20 Australians have been killed fighting with the terrorists — including Melbourne suicide bomber Jake Bilardi — while 140 Australians have aided their cause.

ISIS, with its fighting force of between 9,000 to 18,000 men and women in Iraq and Syria, has used social media as its prime recruiting tool.

And more than 46,000 Twitter accounts are linked to supporters of the terror group, a Brookings Institution report recently found.

“Given the sense of a wide breadth of people in the groups like that — for example if you take Jihadi John who is the beheader who studied in London for computers — you’ve got that capability within the organisation,” said Mr Mansfield.

The documents — labelled a “Technical Expert Account Archive” and posted online on March 23 — unveil strategies to mitigate against spy threats for potential ISIS recruits, current fighters and those wishing to wage jihad on home soil.

One of the files states: “Malware is software used to harm our fellow supporters and soldiers of the Caliphate State by working in many different ways. These include, but are not limited to: disable computer and collect sensitive information, and impersonate the user figure to send spam Action (spam) or counterfeit messages, or access to computer systems.”

Towards the end, attacking techniques on personal computers and websites — known as Denial of Service (DoS) and Direct Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks — are broached.

The Senate last week passed the Federal Government’s controversial metadata laws — crucial, it claimed, to thwarting terrorism attacks and prevent serious crime.

Under the legislation, telecommunications providers will be forced to keep records of phone and internet use for two years in the event security agencies want to access them.

Metadata includes the identity of a user and the source, destination, date, time, duration and type of communication.

The content of a message, phone call or email and web-browsing history is excluded.