A boom in hidden camera tech makes it difficult to spot devices — and the law is complex

Three women on holiday were horrified to discover a carefully hidden camera in the bathroom. It’s a growing trend that’s getting harder to detect.

Three women on holiday in Portugal discovered a carefully hidden video camera in the bathroom that was set to capture them while they showered.

Rubee Woo took to Facebook to recount their horror find in an apartment rental in the Portuguese tourist hotspot of Porto, explaining that her friend noticed something off about a power outlet.

“We quickly packed our bags, handed the apartment keys to the police and left. By the time we reached the hotel, it was 5am,” Ms Woo wrote.

It’s part of a growing trend that experts say is made possible by a boom in the sale of household objects that appear perfectly normal but conceal recording devices.

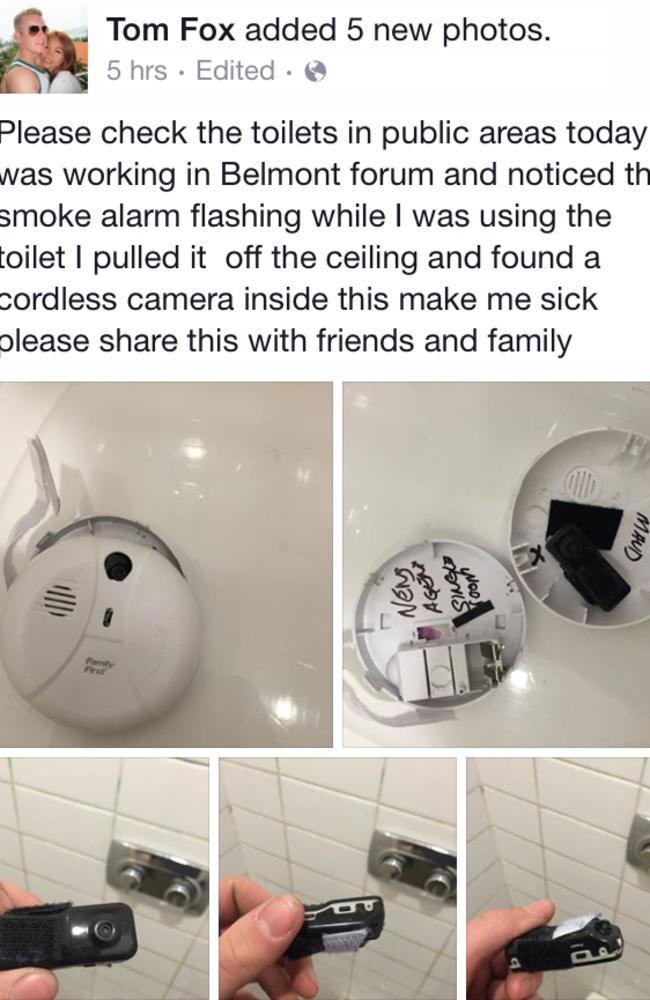

With a few clicks of a mouse, virtually anyone can purchase hi-tech devices that would’ve once been the stuff of spy films — an alarm clock, pen, car key fob or smoke detector that also conceal recording devices.

A number of Australian-based websites market and sell hidden camera items, which have plummeted in price as demand has grown in recent years, and experts warn the laws protecting innocent people from misuse and abuse are inconsistent and inadequate.

“Fifteen years ago, the technology that was available was expensive and a bit quirky and was mostly bought by law enforcement, private investigators and uber geeks,” Bruce Baer Arnold, an associate professor of law and justice at Canberra University, explains.

“But we’re seeing the Kmart effect where availability has boomed and prices have fallen, so now anybody can get their hands on them.”

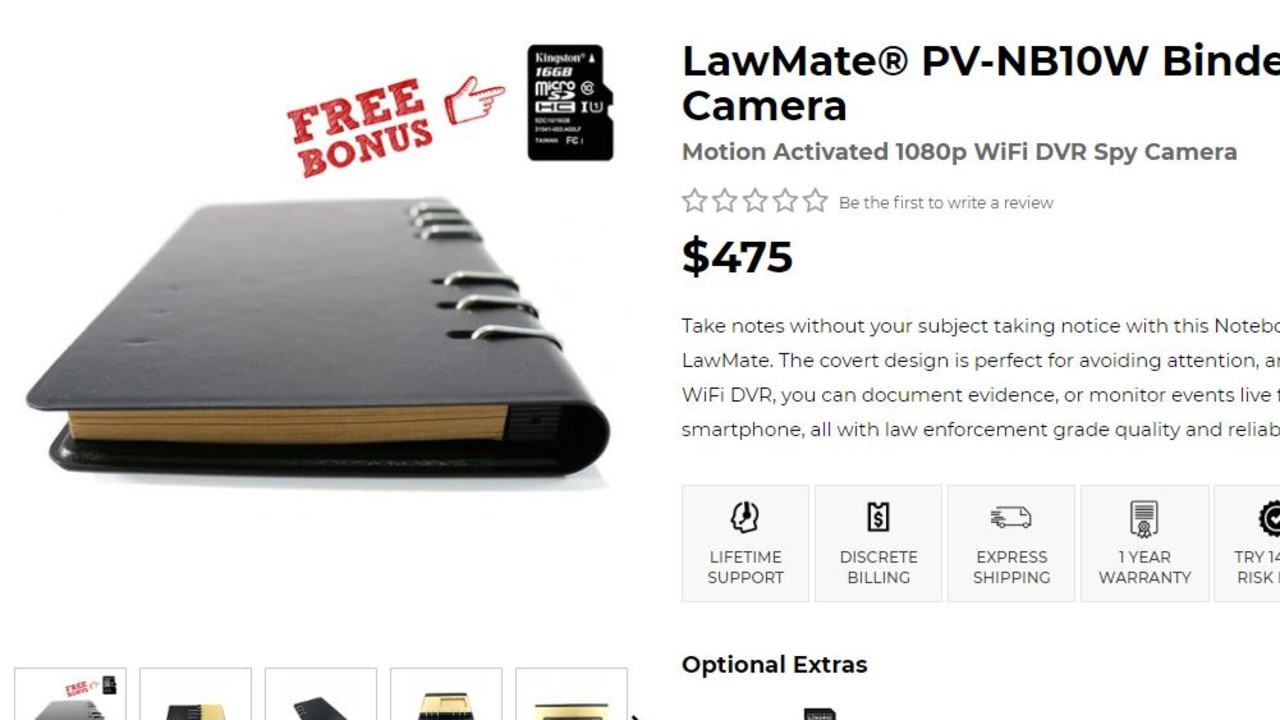

On one local site, a child’s night light, a pair of headphones, a computer mouse and a car cigarette lighter phone charger are some of the objects that conceal cameras.

Watches, picture frames, wall clocks, TV remotes, notebooks and music speakers with hidden video recorders installed are also available.

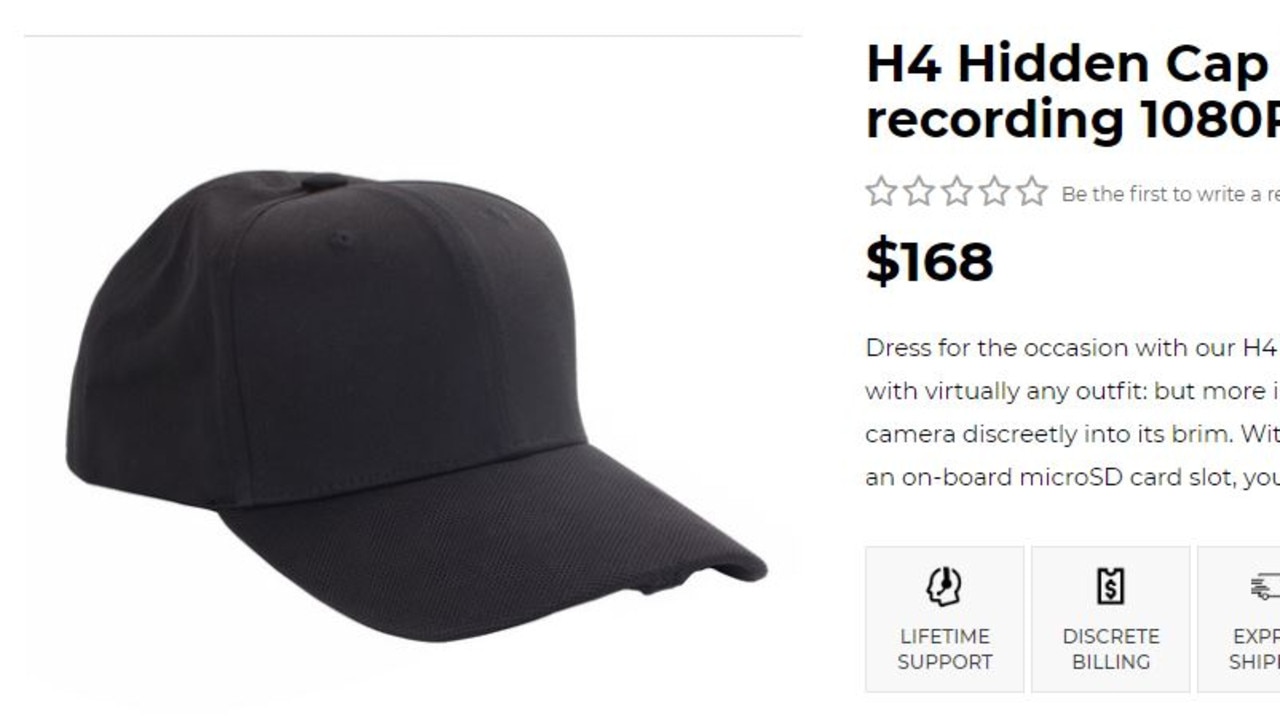

A bedside table alarm clock with invisible camera lens will set you back about $200, while a baseball cap with video recording capability is $168.

“We don’t have any real standards or control mechanisms for the development and sale of these devices,” University of Technology Sydney law professor Kristopher Wilson said.

“That’s an issue for cyber security as well as privacy. There’s a plethora of flow-on effects from this.”

RELATED: Woman finds hidden camera in Bondi hostel bathroom

Recent cases in the United States and Europe of Airbnb guests discovering hidden cameras have raised concerns about the availability of technology.

A number of websites have popped up providing tips for travellers on how to spot devices that might be concealed in ordinary objects, but they’re far from guaranteed.

In 2013, a New South Wales policeman was convicted of secretly filming himself having sex with three women via an alarm clock with a camera hidden inside. He edited together “highlights” videos and shared them with countless colleagues.

He received 200 hours of community service.

A number of Australian cases have dealt with the use of hidden camera devices, from a policeman who recorded himself having sex with women without their knowledge to a man who installed a pinhole camera in his workplace toilet.

In April, a Sydney building manager was jailed for secretly recording his tenants showering, sleeping, using the toilet and having sex. The cameras were discovered when a resident became suspicious of a clock inside an apartment.

But a number of other sinister uses for the technology are emerging.

“An emerging problem is ‘cyber gaslighting’ where these kind of devices are being used in domestic violence situations,” Mr Wilson said.

“It might be a husband who installs them to monitor his wife’s movements to harass and intimidate. It’s a relatively new phenomenon.”

Should a case occur here where an Airbnb guest was secretly filmed, successful prosecution of the perpetrator could depend on the state or territory.

In NSW, such a scenario “falls smack bang in the middle of a major gap in the law”, Mr Wilson said.

Alison Barrett, principal lawyer at the firm Maurice Blackburn, said Airbnb had a policy requiring hosts to disclose the presence of any surveillance devices.

“If they’re disclosed in the advertisement, it’s OK to use them, subject to them not being in a private place like a toilet or bathroom,” Ms Barrett said.

“Generally, laws in each of the states say you can’t have a hidden camera or make a recording in a place where someone has a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

Dr Baer Arnold said context was key when it comes to determining the legality of the use of these devices, which raises a whole host of issues.

“Context obviously matters, so if we’re talking about people in an intimate situation, in a bathroom or toilet, certainly in the bedroom, law will often cope with that reasonably well,” he said.

“The big issue we’ve got is that the law is so profoundly inconsistent between the states and territories. And then there are cases where a potential offence would be dealt with by Commonwealth laws.

“It’s all a bit rocky, and some of the laws have been shown to be outdated. We’ve had instances in the past where an invasion of privacy with a video recording was deemed fine because the sound was off. That’s a bizarre situation.”

Another issue is that victims of misuse mightn’t want to come forward for fear of having their private lives further exposes, he said.

RELATED: Company denies backpacker’s hidden camera claim

An Australian Law Reform Commission report released in 2014 warned of the glaring gaps in legislation, which could leave victims of misuse without adequate recourse.

But Mr Wilson said the warnings appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

“Other priorities have popped up, I think,” he said. “There’s a tendency to create a specific offence in response to a widely reported issue rather than look at more broadly what’s going on.”

Dr Baer Arnold said there’s an urgent need for consistency at the state and territory level and uniform legislation adopted across the board.

“And we need national privacy tort, legal courses of action, when privacy is invaded,” he said.

There’s also a conversation about scenarios when it could be argued that using this type of technology is imperative.

Hidden cameras that expose the abuse or mistreatment of children, the elderly or other vulnerable populations could be deemed beneficial.

“Law in Australia overall is still playing catch up,” he said.

Ms Barrett said it’s a tricky balance between protecting privacy and potentially uncovering instances of abuse.

“Consistent, uniform laws would be a good place to start,” she said.

Restricting the sale of the technology is unlikely to be an effective response, Dr Baer Arnold says, and so the more effective response is to have robust legal protections in place.

“Like all technology, it can be used for good and it can be used for bad,” he said.

“Take drone technology. Drones can protect the environment and help in emergencies. They can also be used to spy and to kill. It’s about context. Just restricting something doesn’t work.”