Remote Amazon tribe finally connects to internet — only to wind up hooked on porn, social media

A reclusive tribe in the Amazon finally got hooked up to the internet — only to be torn apart by social media and porn addiction.

A reclusive tribe in the Amazon finally got hooked up to the internet, thanks to Elon Musk — only to be torn apart by social media and pornography addiction, elders complain.

Brazil’s 2000-member Marubo tribe has been left bitterly divided by the arrival of the Tesla founder’s Starlink service nine months ago, which connected the remote rainforest community along the Ituí River to the web for the first time.

“When it arrived, everyone was happy,” Tsainama Marubo, 73, told The New York Times. “But now, things have gotten worse. Young people have gotten lazy because of the internet, they’re learning the ways of the white people.”

The Marubo are a chaste tribe, who even frown upon kissing in public — but Alfredo Marubo (all Marubo use the same last name) said he is anxious that the arrival of the service, which delivers super-fast internet to far-flung corners of the planet and has been billed as a game-changer by Mr Musk, could up-end standards of decorum.

Alfredo said many young Marubo men have been sharing porn videos in group chats and he has already observed more “aggressive sexual behaviour” in some of them.

“We’re worried young people are going to want to try it,” he said of the kinky sex acts they’ve suddenly been exposed to on screen. “Everyone is so connected that sometimes they don’t even talk to their own family.”

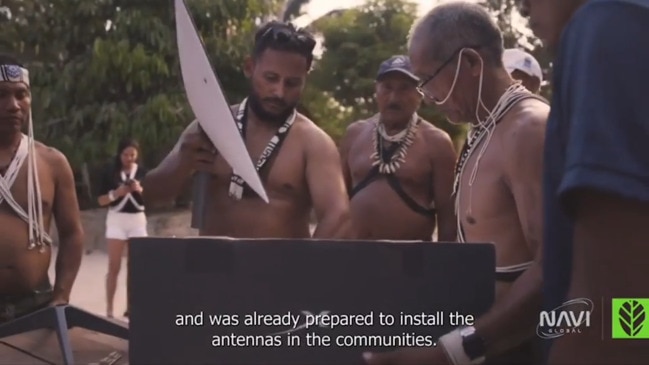

Starlink works by connecting antennas to 6000 low-orbiting satellites. The necessary antennas were donated to the tribe by American entrepreneur Allyson Reneau.

Initially, the internet was heralded as a positive for the remote tribe who were able to quickly contact authorities for help with emergencies, including potentially deadly snake bites.

“It’s already saved lives,” Enoque Marubo, 40, stated.

Members are also able to share educational resources with other Amazonian tribes and connect with friends and family who now live elsewhere.

It has also opened up a world of possibilities for young Marubo, some of whom have been unable to conceptualise what lays beyond their immediate surrounds.

One teen told The Times that she now dreams of travelling of the world, while another says she aspires to become a dentist in São Paulo.

However, Enoque also complained of the significant downsides.

“It changed the routine so much that it was detrimental,” he stated. “In the village, if you don’t hunt, fish and plant, you don’t eat.”

“Some young people maintain our traditions,” TamaSay Marubo, 42, added. “Others just want to spend the whole afternoon on their phones.”

Tribespeople became so addicted that Marubo leaders, fearing that history and culture — which is passed down orally — could be lost forever, they have now limited access to the internet for two hours each morning, five hours each evening, and all day Sunday.

But parents still worry the damage may already be done.

Another father, Kâipa Marubo, said he’s anxious about his children playing violent first-person shooter games.

“I’m worried that they’re suddenly going to want to mimic them,” he stated.

Meanwhile, others say that they’ve fallen victim to internet scams given that they lack digital literacy, while many youngsters are chatting with strangers on social media.

Flora Dutra, a Brazilian activist who works with indigenous tribes, was instrumental in helping connect the Marubo to the internet.

She believes anxieties about the internet are inflated, and asserts that most tribespeople “wanted and deserved” access to the world wide web.

Still, some officials in Brazil have criticised the rollout to the remote communities, saying special cultures and customs could now be lost forever.

“This is called ethnocentrism,” Ms Dutra said of such critiques. “The white man thinking they know what’s best.”

This article originally appeared on NY Post and was reproduced with permission