Google reckons with an increasingly activist workforce amid accusations of union busting and facilitating human rights abuses

Former Google employees who claim they were forced out for speaking up while they worked at the company are now doing it publicly.

Google and massive technology companies like it are coming under increased scrutiny as regulators begin questioning their size and whether current laws provide adequate checks on their power, but the search and advertising giant in particular has an emerging new threat: its own employees.

At the start of the millennium a job at Google was one of the most highly sought after positions in the technology industry, a mood that has persisted for the better part of two decades.

The company is known for the perks it offers to workers (several of which are already guaranteed to Australians regardless of the company they work for thanks to the National Employment Standards).

It’s also a large company that gives aspiring workers (known as “Googlers”) the chance to collaborate with some of the best minds in tech.

But in recent months, stories have begun leaking out of the company as an increasing flow of employees depart.

Stories of bullying, harassment and discrimination in the workplace as well as concerns over the kind of work the company does and who for have led to a number of scandals.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where or when things began to shift, but October 2014 is a good place to start.

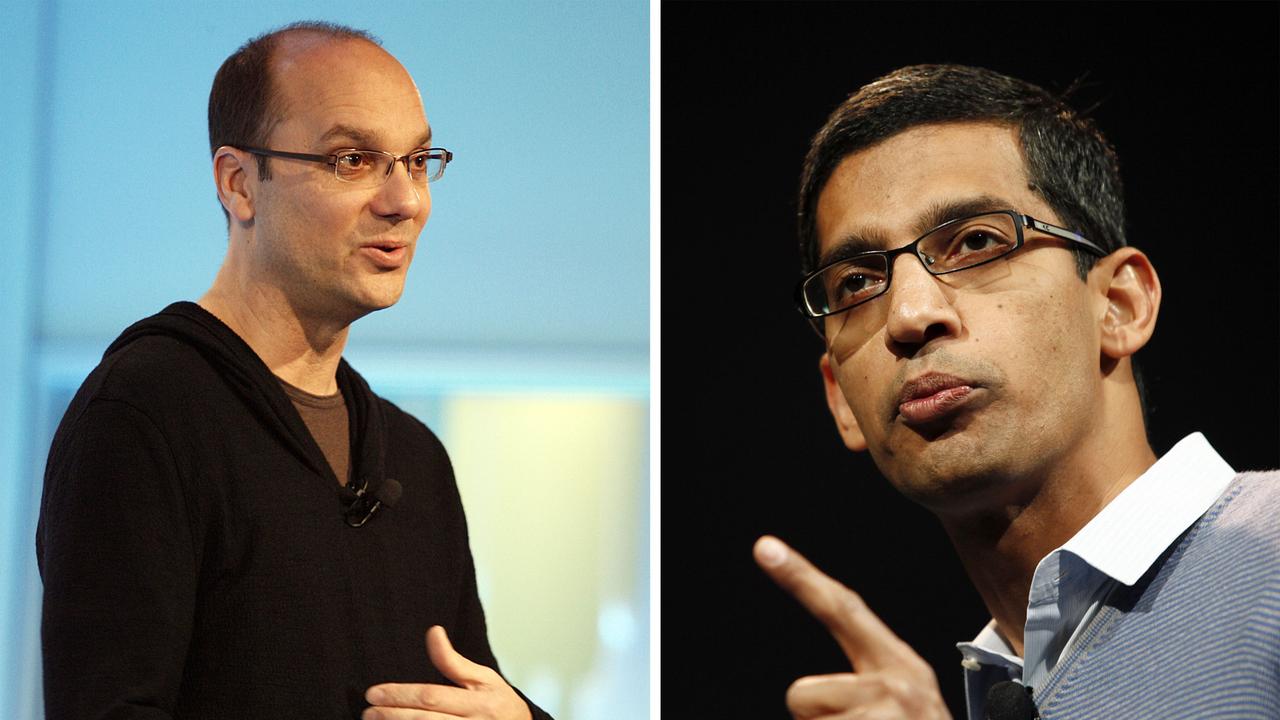

That’s the month the company said goodbye to Andy Rubin, one of the creators of the Android mobile operating system Google acquired in 2005 that is now the most used in the world.

At the time he was given a glowing farewell, praised for creating something “truly remarkable” by then Google CEO Larry Page, who recently stepped down from the company himself alongside his co-founder Sergey Brin.

Four years later, the New York Times revealed that Mr Page had actually asked Rubin to leave after an internal investigation decided accusations of sexual misconduct against Rubin from a former employee were credible. A spokesman for Rubin told the NYT after that article was published that the allegations were false.

Rather than simply firing Rubin, the company reportedly accepted his resignation, agreed to pay him $2 million a month for four years, and even invested in his next venture Essential Phone.

Following the news of the allegations against Rubin, tens of thousands of Googlers around the world staged a walkout in protest in November 2018.

“Hi. I’m not at my desk because I’m walking out in solidarity with other Googlers and contractors to protest sexual harassment, misconduct, lack of transparency, and a workplace culture that’s not working for everyone. I’ll be back at my desk later. I walked out for real change,” a flyer left at the desk of some who walked out said.

One of the organisers of that walkout, Claire Stapleton, recently wrote in Elle magazine that the walkout showed there were more issues in the company than a few instances of sexual misconduct by executives.

“It was clear this wasn’t just about Andy Rubin anymore,” wrote Ms Stapleton, who helped craft Google’s narrative as part of its communications and marketing teams over her 12 year tenure at the company.

Ms Stapleton was escorted out of the building by security on her last day at the company in May, leaving after a “reorganisation” that saw her essentially demoted.

Andy Rubin had been given millions to quietly quit his job. By her account, Ms Stapleton had her job incrementally taken away from her for speaking up, until she finally let it go.

She’s not alone.

Last month, Kathryn Spiers recounted how she had been terminated, which Google said was for violating the company’s security policies.

“Part of my job was to write browser notifications so that my co-workers can be automatically notified of employee guidelines and company policies while they surf the web. I was very good at my job and Google has acknowledged this,” she said, citing three recent performance reviews in a post on Medium.

Ms Spiers said she wasn’t told how she violated the company’s security policies, but it appears to have something to do with a small browser notification that popped up in Chrome browsers when Googlers visited the company’s community guidelines, or for the website of IRI Consultants, a firm known for its anti-union work that had recently been hired by Google.

“Googlers have the right to participate in protected concerted activities,” Ms Spiers’ browser pop-up read.

Google later said it had “dismissed an employee who abused privileged access to modify an internal security tool,” which by Ms Spiers account, is part of her job.

Her termination came a few weeks after Google fired four employees who had been active in unionisation efforts.

They later became known as the “thanksgiving Four”; their firings coming a few days before one of the United States’ biggest national holidays.

Google claimed the workers were fired for looking at documents that didn’t pertain to their work.

In anotherMedium post, an account appearing to represent the Google Walkout movement going back as far as November 2018 accused the company of union busting, saying the company had only recently changed its policies, after hiring IRI Consultants, to make that a fireable offence.

“Let’s be clear, looking at such documents is a big part of Google culture; the company describes it as a benefit in recruiting, and even encourages new hires to read docs from projects all across the company,” the post reads, adding that the policy was unclear on what documents would be off limits, but explicitly said they wouldn’t have to be labelled as such.

“No meaningful guidance has ever been offered on how employees could consistently comply with this policy. The policy change amounted to: access at your own risk and let executives figure out whether you should be punished after the fact.”

The accusations of misconduct at Google haven’t stayed in the last decade either.

Earlier this week, Google’s former head of international relations levelled several more serious accusations against the company.

Ross LaJeunesse joined Google in 2008, and is now running for the US Senate on a platform of tighter regulations for big tech.

Two years after he joined, Google pulled out of the Chinese market over pressure being placed on it to censor search results.

“I argued strenuously against these plans, knowing that a complete turnaround in our approach would make us complicit in human rights violations, and cause outrage among civil society and the many western governments which had applauded our 2010 decision,” Mr LaJeunesse wrote on Medium.

After being promoted to head of international relations, Mr LaJeunesse said he was continually pushed to re-enter China.

“I was alarmed when I learned in 2017 that the company had begun moving forward with the development of a new version of a censored search product for China, codenamed ‘Dragonfly,’” Mr LaJeunesse said, adding that was one of many concerning developments.

“That completely surprised me, and made it clear to me that I no longer had the ability to influence the numerous product developments and deals being pursued by the company,” he wrote.

Thousands of Googlers have also protested in the past over programs, support and services the company has supplied to the US Department of Defence, as well as its immigration and border protection agencies.

Mr LaJeunesse said he began advocating for programs to publicly commit Google to adhere to human rights principles, which senior executives repeatedly came up with excuses not to do so.

Mr LaJeunesse also claimed to witness discrimination, harassment and bullying in the workplace during his time there.

The accusations include senior colleagues bullying and screaming at young women and making them cry at their desk, as well as “diversity exercises” where employees were placed in groups labelled “homos”, “Asians”, and “Brown people” while participants shouted out stereotypes.

Mr LaJeunesse claims there were 90 policy positions vacant when he was told there were no positions available for him after a “reorganisation”, “despite 11 years of glowing performance reviews and near-perfect scores on Google’s 360-performance evaluations, and despite being a member of the elite Foundation Program reserved for Google’s ‘most critical talent’ who are ‘key to Google’s current and future success’.”

He claims he was offered a significantly reduced role at the company after hiring counsel, which would involve him staying silent about the issue.

Google disputes that last bit.

“We have an unwavering commitment to supporting human rights organisations and efforts. That commitment is unrelated to and unaffected by the reorganisation of our policy team, which was widely reported and which impacted many members of the team. As part of this reorganisation, Ross was offered a new position at the exact same level and compensation, which he declined to accept. We wish Ross all the best with his political ambitions,” a Google spokesperson wrote in an email to news.com.au.

Google was also asked about its stance on unionisation at the company and in general, whether it had ever taken action to stop workers organising, and whether it could confirm or indeed deny any of the instances of bullying and harassment Mr LaJeunesse claimed to witness, but those questions went unanswered.

Mr LaJeunesse said “things have changed” in the company and that it has abandoned its unofficial motto of “don’t be evil”.

To be clear, it hasn’t been completely discarded. While it’s no longer the company’s official motto, it remains buried at the bottom of its code of conduct.

“And remember … don’t be evil, and if you see something that you think isn’t right – speak up!”

Missing from the code of conduct is a warning to those mouthy Googlers they should be prepared to look for a new job if they do.

Do you think big tech companies need tighter regulations? Let us know what you think in the comments below.