Nissan’s ex-NASA man says self- driving vehicles still need humans

Future autonomous vehicles promise a lot, says Nissan’s ex-NASA man Maarten Serhuis, but still will need a driver.

The man plotting Nissan’s autonomous vehicle strategies got most of his inspiration in places with few cars and no roads.

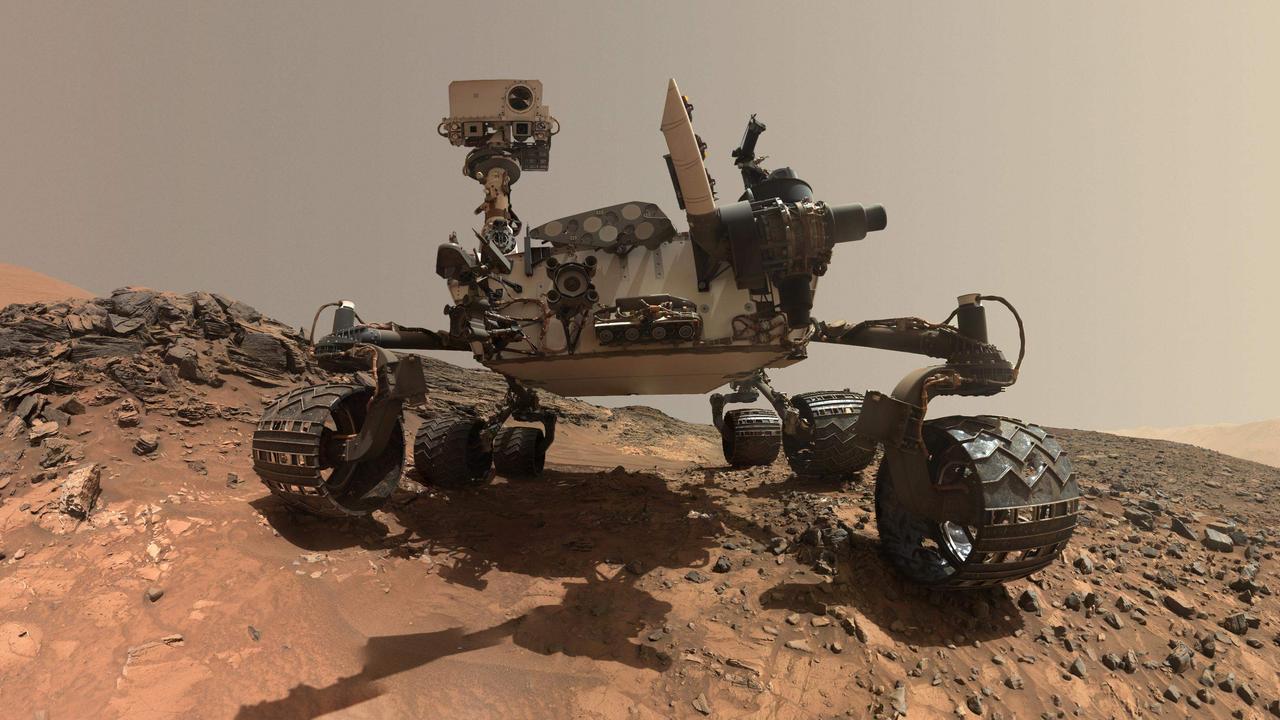

Chief technology director Maarten Serhuis works in Silicon Valley but relies on the ideas he gained from trials in the deserts of Australia and Utah, and the North Pole, when he was a lead researcher for NASA Mars missions.

For all the future possibilities of autonomous vehicles in eliminating road tolls and boosting productivity, Serhuis says, there still will need to be a driver for a long time yet.

Connecting the two careers, Serhuis says, “You need to develop technology for people. To develop a real autonomous system in society where it will be interacting with people all the time will be challenging and interesting, I thought would be really cool.

“We’re not going to Mars any time soon so I thought, why don’t I help develop something on Earth that really helps people?

“I worked on intelligent autonomous agent systems in mission control running on the space suits of the astronauts — if people on Mars don’t have communications with Earth, say a 30 minute delay, how do they need to be supported to work as teams.

“How would we make these systems work on the road? It wasn’t very long before I thought, this needs humans in the loop.

“We have aeroplanes with two pilots yet we still have air traffic controllers. Why do we think we can have millions of vehicles driving around and not needing any human interaction?”

Initially, Nissan colleagues queried whether humans fitted into autonomous scenarios. Serhuis came up with numerous examples.

“I asked, what is the system going to do when it has to break rules? How are you going to define when and how?” he says. “People have this impression that autonomy doesn’t need interaction. We as humans don’t even do that.

“Some start-ups are doing remote driving. I think that is the wrong way. I think it’s safer to have the car be autonomous and make safety-critical decisions itself other than people at a distance doing that.”

However, he says, the “robo services” to be deployed in the next 10 years will show how such operations use the tech and gain public trust.

“There are situations where ‘human in the loop’ isn’t fast enough,” he says. “Where you can have a go-or-no-go decision, negotiate a lot of traffic, someone jumping in front of you, the car needs to take safety into account, act and react, avoid obstacles. The autonomous car can see 360 degrees … humans cannot.”

For humans, there are still the paths of choice and aspiration.

“Nobody can control, if you buy a vehicle, where you drive,” Serhuis says. “It’s the owner of the vehicle that will control where you drive. What is the value of a vehicle that doesn’t go where you want?

“Every society needs to decide what task is good for humans to do and for machines to do. We’ll be answering these questions for the next 20 years, in manufacturing, food service, every part of human activity.

“The value of this technology for people that are now not mobile. Mobility is going to be, in the next century, the biggest differentiator. If we can provide people with easy, cheap and personal mobility, there’s the value.”