‘You will kill this veteran’: Inside the bureaucratic nightmare that pushes too many over the edge

It can come down to a single word in a report or a number on a scale – but for these Aussies, it can be the difference between life and death.

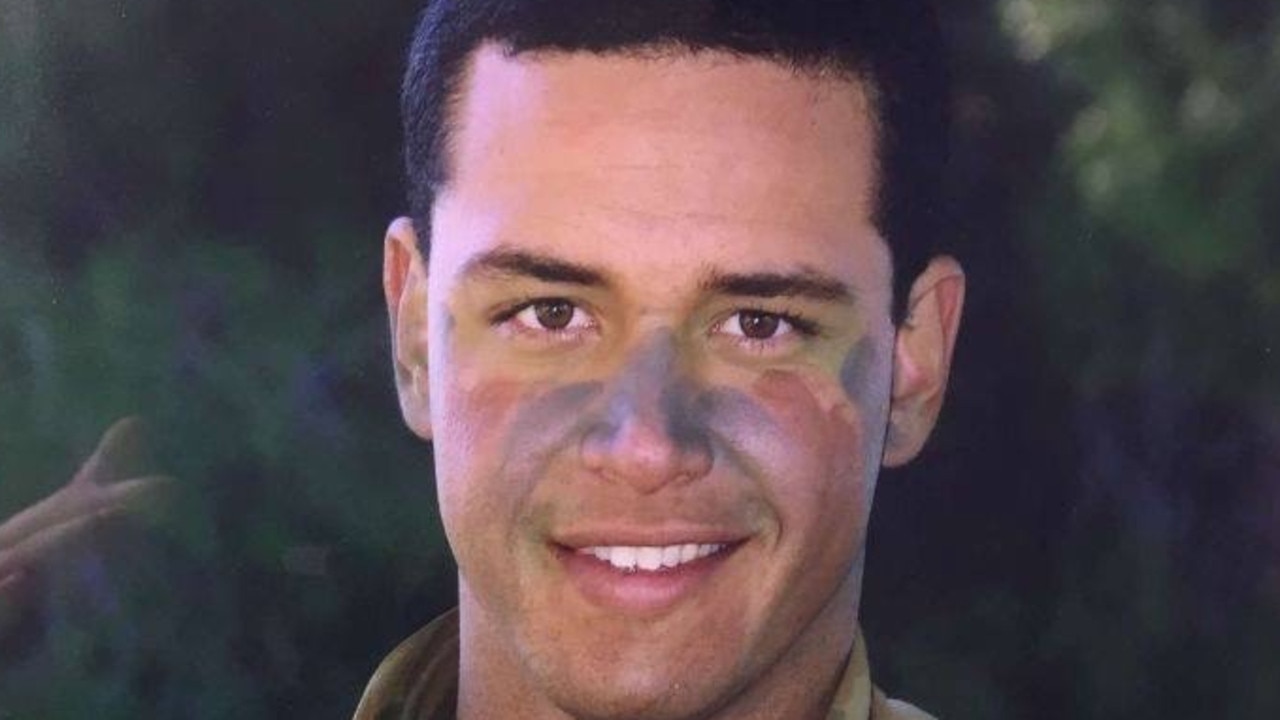

An Afghanistan war veteran who suffers from severe depression and PTSD has opened up about the “bureaucratic, malicious” compensation claims process that, for too many of Australia’s war heroes, is often the final straw.

Sometimes, as he found out, it can come down to a single word in a psychiatrist’s report, or a single point on an assessment scale.

From the point of view of veterans – who are often struggling to adjust to post-service life while nursing battered bodies and mental scars – the process can be agonisingly slow, convoluted, and at times almost Kafkaesque.

“Bureaucratic and malicious are the two words I would use,” said Hunter, who asked not to use his real name.

Australia is in the grip of a veteran suicide crisis.

More than a dozen veterans have died by suicide this year alone – roughly one per week.

Since Australian forces were deployed to Afghanistan in 2001, more than 600 ex-servicemembers have taken their own lives.

Bowing to mounting pressure, Prime Minister Scott Morrison last month announced a royal commission into veteran suicide.

Veterans Affairs staff have begged for more resources to cope with a growing backlog of tens of thousands of claims.

Many injured veterans are left waiting up to a year to even be assigned a case manager.

The mother of Afghanistan veteran Jesse Bird, who died by suicide in 2017, directly blamed DVA’s “poor processes” for her son’s death.

“Jesse started the claims process in 2015, but he died with rejection letters surrounding him in June 2017,” Karen Bird told The Australian last month.

“They dumped money into his account two weeks after he died.”

Hunter, despite being suicidal in the past, says he hadn’t been “big on bashing the drum about the veteran mental health space”, until he experienced the torturous process first-hand.

Despite giving 17 years of his life to the infantry – he celebrated his 19th birthday at Kapooka – he was unceremoniously shown the door last year after being diagnosed with a chronic illness.

“I didn’t want to go medically – I wanted to stay and fight on,” he said.

After his diagnosis, he was told “in no uncertain terms that my career in the Army was basically over”. He was advised to get all of his claims lodged and approved before leaving the service.

Luckily, he says, most of his physical injuries – backs, hips, shoulders, hearing – were fairly cut and dry.

Where he ran into trouble was his mental health claim.

The permanent impairment stream, which determines what level of ongoing support a veteran is entitled to once their injury claims have been accepted, works on a points system going up to 80.

Losing a leg might be worth 70 points, for example, but a bad knee might be 10 points.

Reaching the magic number of 60 entitles the veteran to a Gold Card, guaranteeing them free medical care.

PI assessment for mental health claims such as post-traumatic stress disorder – which, due to increased awareness, are much more common now than among older veterans – can be more complicated.

“I would say there is some level of discretion (given to the assessor) because there is some ambiguity of injury,” he said.

In his case, however, there was no ambiguity at all.

Hunter, who has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder and has been through the “full gamut” of medical assessment and treatments, provided DVA with his psychiatrist’s report concluding that his conditions were both “permanent and stable”.

Two weeks before he was due to leave the service, DVA came back with what’s known as an interim decision.

The assessor, explicitly rejecting the doctor’s report, relied on an older report from the same psychiatrist to say it was their belief that his condition was permanent, but “not yet stable”.

Conveniently, the decision landed him on 59 points – one shy of a Gold Card.

“This is the key to my real grievance,” he said.

“The person at DVA doing this assessment is not medically trained. They rely on the medical evidence from the psychiatrist … but all of a sudden you have a delegate who says, ‘This is our opinion’.”

Hunter, with the help of his representatives, Luke Armstrong and Matthew Dumars, appealed the interim decision to the Veterans Review Board, an independent tribunal that can review DVA rulings.

They requested VRB review the decision, taking into account the psychiatrist’s most recent report.

But what followed was another bizarre series of roadblocks – first DVA, through a clerical error, omitted several covering pages from the psychiatrist’s report when it forwarded Hunter’s full personnel file to the VRB.

The VRB member, himself a veteran, suggested the file had been tampered with, and requested a copy of the original report be sent.

But when the doctor’s office did so – along with an email confirming Hunter’s diagnosis – the member suggested that the signature image used on the email did not match the report.

He asked to be provided further proof from the psychiatrist, who refused – as Mr Armstrong put it, because it was “not his rooms’ fault, and they do not have time to go back and forward” about the VRB’s “calligraphy interrogation”.

That left Hunter at a standstill.

Mr Armstrong, an Air Force veteran, later sent a furious email to the member and the VRB accusing them of “adversarial behaviour”.

“You have been provided all information required, and yet, still want to move the goalposts, unnecessarily,” he wrote.

“You will kill this veteran acting the way you are. This is the veteran suicide issue in a nutshell. It is a sad state when people like you decide you’d prefer to play games than help a veteran.”

He also wrote to Veterans’ Affairs Minister Darren Chester and DVA Secretary Elizabeth Cosson to complain about the handling of Hunter’s case.

In response, VRB head Jane Anderson said in a letter that under the law, “representatives before the VRB are expected to treat staff, members and other parties with respect and courtesy”.

“I would also take this opportunity to assure you that the VRB prioritises putting veterans at the front and centre of their applications, and that VRB processes are aimed at resolving applications fairly, justly, informally, economically and quickly,” she said.

This week, prior to publication of this article, the VRB made a favourable determination in Hunter’s case.

But he said he still wanted to speak about the experience to highlight the “horrible and hopelessly inadequate system faced by veterans”.

Spokespeople for both the DVA and VRB said they did not comment on individual applications.

“It is incorrect to assert that claims delegates deliberately try to minimise claims outcomes for veterans,” a DVA spokesman said.

“Decisions are required to be made under the relevant legislation and delegates work hard to achieve the most favourable outcomes for veterans.”

The spokesman said DVA’s claims delegates assessed each claim “based on all of the medical evidence provided at the time of the claim being submitted” and that “where further information is received after the original submission, it enables the delegate to reassess the claim with this new information”.

He noted that in the last financial year DVA made 95,667 compensation decisions, with 71 per cent receiving a positive determination.

“Where some rejected decisions are overturned at appeal, in many instances this is because new information has been provided as part of the review process that wasn’t available to the delegate at the time of the original decision,” he said.

“The veteran community can be assured that their physical and mental wellbeing is DVAs number one priority. The government provides DVA with $11.5 billion every year to support veterans and their families and DVA take this responsibility extremely seriously.”

In a statement, VRB’s Ms Anderson said the body was “at the forefront of modern administrative review, using Alternative Dispute Resolution to resolve approximately 80 per cent of veterans’ applications”.

“ADR aims to resolve veterans’ applications informally and quickly without the need for the veteran to attend a legal hearing, and delivers outcomes that are lawful, effective and acceptable to the veteran,” she said.

Ms Anderson added that the VRB’s recently introduced online pathway was seeing some applications being resolved in under two weeks.

“(This) demonstrates the VRB’s commitment to deliver justice and meet the needs of a diverse and evolving range of veterans and current serving members,” she said.

Mr Armstrong, for his part, argues that while DVA is often the “straw that breaks the camel’s back”, it’s the culture of abuse – physical, sexual and mental – inside the Defence Force that’s the real culprit.

“This is a very unpopular opinion – DVA aren’t that bad,” he said.

“When people come to the DVA or VRB they’re already broken because of Defence, in particular, due to the abuse. Hence, it doesn’t take much to push them over the edge. Where the departments could significantly improve, is in people like Hunter’s situation.”

Mr Armstrong, who experienced abuse himself during his service, welcomed the announcement of the royal commission but said he hoped it focused on the root causes, rather than solely the DVA.

Members of the public have been invited to make submissions that will inform the terms of reference for the commission. The consultation period closes on May 21.

“People join the ADF, on paper being fit and healthy, then leave suicidal,” Mr Armstrong said. “Something changes.”