Newington Armory, the suburban navy base that was vital to Australia’s defence

Today they’re hidden away close to Sydney Harbour but in the 1940s this warren of pitch black passages helped save Australia.

On the upper reaches of Sydney Harbour a rivercat rumbles past.

Nearby the tips of Sydney’s Olympic stadium can be seen, frequently echoing to the roars of footy fans.

But between the two all is quiet around a scattered jumble of quaint, turn of the century buildings.

Look closer and there are signs this is not a normal place. Most buildings sit beside massive, foreboding concrete walls. Other structures are barely visible, hidden below high earth banks.

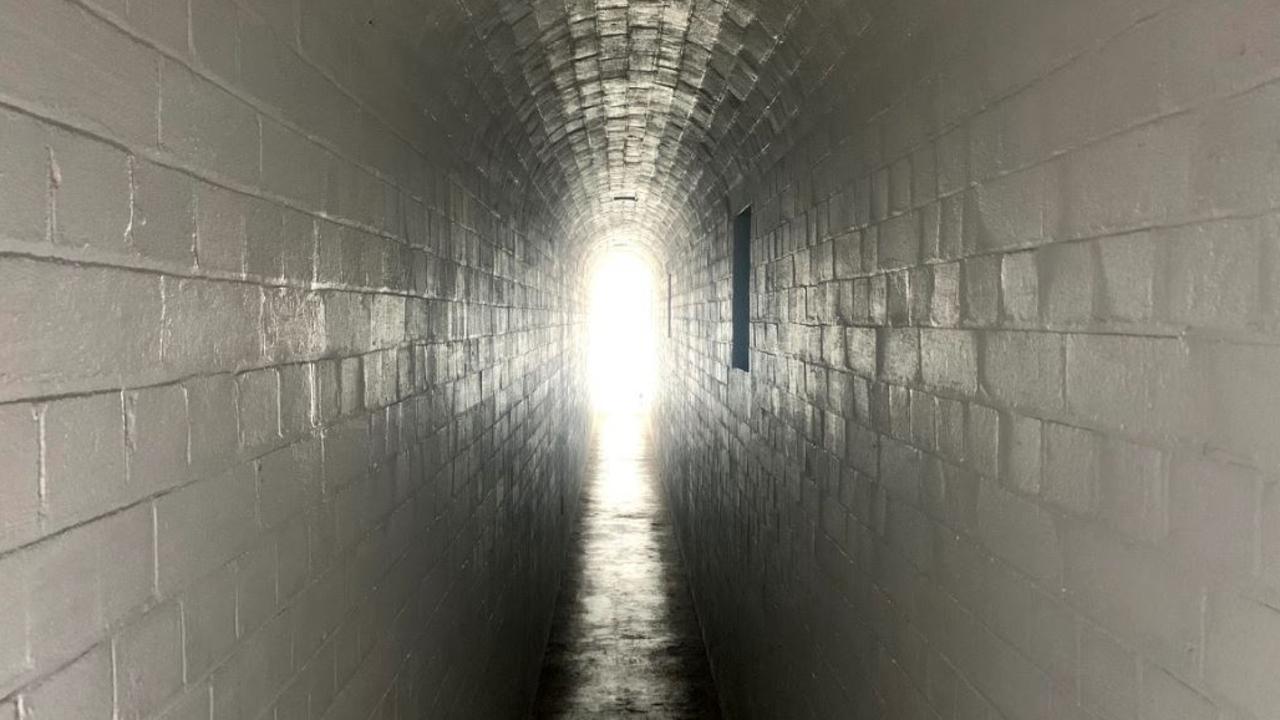

Out of sight, pitch black semisubterranean corridors crisscross a place that was once of the most sensitive, and secret, in Australia.

It’s a site that used to house an enormous arsenal of defence — and of death. Three people died within its grounds, one a child.

It played a critical role in protecting not just Sydney, but the whole of Australia and the Pacific.

Without Newington Armory, Australia would have been fair game for any would be invaders. And if invasion did happen, there were plans to raze the armory to the ground so the enemy couldn’t access its valuable material.

There was some “serious firepower” here, says Fiona Tucker, who works at Newington Armory.

“This place was vital for Australia, particularly in World War II when it was crucial in the supply of armaments to the Allied fleets in the Pacific.”

For 102 years, from 1897 to 1999, Royal Australian Navy Armaments Depot (RANAD) Newington — as it was then called — was one of the country’s most important stores of weaponry. Gunpowder and shells, and, later missiles and torpedoes, were all tucked away just 20kms west of the CBD.

Next Saturday, November 2, there’s the chance to experience the weapons depot after dark as part of Sydney Open, an annual event where usually restricted buildings throw open their doors so everyone can have a sticky beak inside.

RANAD Newington was a well oiled war machine.

“Military ships coming into Sydney Harbour would deammunition. All the things that go bang would come off,” Ms Tucker, who is the manager of visitor programs at Sydney Olympic Park, told news.com.au.

“The munitions would come up the (Parramatta) River packed on special concrete barges with the explosive below the water line so if they were attacked from above the water would protect the impact of the explosion.”

Cranes and manpower would unload the ordnance on a dedicated dock and then its own rail network would transport the precious and volatile cargo into the magazine, the name for the stores.

OLDER THAN AUSTRALIA

The Armory wasn’t built by Australian forces, because it’s so old Australia didn’t exist as a country at that point. Rather, it was opened in 1897 by the New South Wales military forces, loyal to Britain.

The site was chosen precisely because, at the time, it was in the “middle of nowhere,” far from the hubbub of Sydney, said Ms Tucker. Just marshland, meadows and mangroves.

The fledgling nation didn’t need that many weapons to begin with. All that changed in the 1940s when Australia was a key player in the Second World War and found itself under attack.

“During World War II it was a busy, bustling place because this site was crucial in the supply of armaments to the fleet in the Pacific. It played a huge role.”

The UK, US and other countries also used the magazine.

“Britain and Australia threw all their stock in together and ran one operation. The Americans ran their own depot within our depot.”

SCORCHED EARTH DENIAL PLAN

RANAD Newington could not be allowed to fall into enemy hands.

“It was absolutely a target,” said Ms Tucker.

“So a ‘scorched earth denial plan’ was in place. If the Japanese made it to Sydney, this site would be rendered useless.”

The weapons would be removed, power ripped out, buildings demolished, even the sheep that helped cut the grass — cutting out risky spark producing lawnmowers — would be dispatched.

“They were going to trash the place.”

The dark walls and earth that surround the structures were designed to minimise the effects of an accidental explosion or air attack.

Their effectiveness was proved in 1975 when two engineers dismantled a torpedo. But something went terribly wrong.

“The wall contained the blast, the windows blew out, the impact of the explosion killed them both. Yet staff outside were only shaken,” said Ms Tucker.

EERIE PITCH BLACK CORRIDORS

One of the eeriest areas of RANAD Newington is the magazine. Half underground, the walls are thick, lights dim and even on a 30C day it feels unnaturally cool inside.

In consecutive caverns, boxes full of shells and fuses reach to the ceiling.

A series of dark and narrow corridors — almost tunnels in places — thread around the stores. Their role was many fold. The space provided an extra buffer for any explosion. Also, dotted throughout, are small crevices with a thick pane of glass separating it from the stores next door.

Candles would be lit in these crevices with the gloomy light reaching just far enough into the cavern so staff could find the right drum or shell. Having a candle within the store itself was far too risky.

The gloomy labyrinth’s role was small but vital to the success of the complex. And in turn to the Allies success in the war.

But isn’t a comforting place to be.

“If I’m in here by myself I’d be sensible, I’d tell someone where I’m going,” said Ms Tucker.

“But I don’t get spooked by it. There’s no stray spirits running around.”

TRAGEDY

Tragedy has struck this place though. As well as the two engineers another death occurred, that of 8-year-old Gerald Muddyman.

Staff families once lived at the base. The kids would run freely in the grounds. In March 1924, Gerald saw a curious object in a fire.

The day before, staff had been dismantling igniters. It was a process that involved tipping the gunpowder into water, rinsing, drying and then burning the casing.

The next day, Gerald poked one of the smouldering drums. It’s likely some gunpowder was still lodged within it.

“Back then nothing could be done for a burns victim. How they treated them was different.

“It’s said they tore the clothes off him. Can you imagine the pain that kid must felt having his burnt flesh ripped off with his clothes? It’s tragic, horrible.”

In the end, it wasn’t a foreign invasion that overcame RANAD Newington. It was the invasion of suburbia.

It was no longer in the middle of nowhere, it was close to one of one of Australia’s biggest jails, a growing residential community and the Olympic Games were going to be held a few kilometres away.

Athletes, spectators, residents and a weapons dump don’t mix.

A new depot is now located far outside of Sydney, close to the southern NSW town of Eden. Part of the Newington site became the Olympic athletes’ village with the rest saved as the current Newington Armory.

Ms Tucker said it was likely that it would be unfit for purpose now anyway.

“It’s progress. Much of what this place was designed for wouldn’t be used now. Warfare has changed.”

Sydney Open is on Saturday 2 — Sunday 3 November including tickets to Newington Armory After Dark at Sydney Olympic Park.