Kevin Rudd warns of ‘hot war’ between China and the US

After decades of relative peace, the risk of a armed conflict between two of the world’s biggest superpowers is now “especially high”.

Kevin Rudd has warned that the risk of a “hot war” between China and the United States that includes actual armed conflict is now “especially high” for the first time since the 1950s.

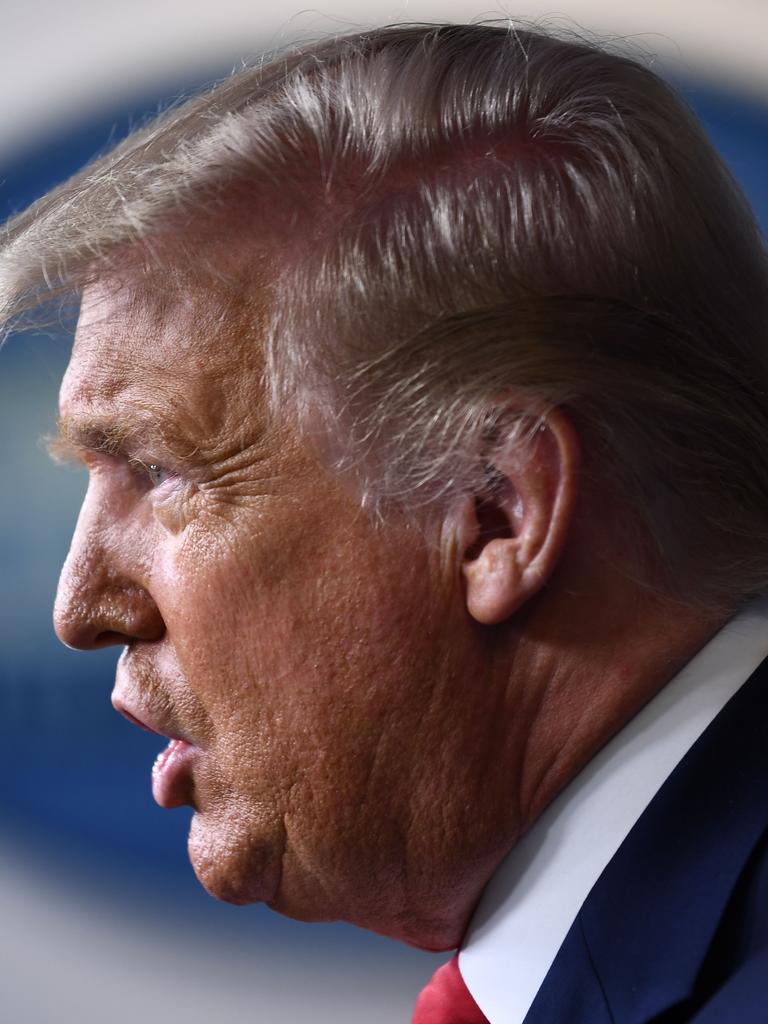

As the chaotic Trump administration counts down to an election, the former prime minister has outlined his fears that the “sabre rattling from both Beijing and Washington has become strident, uncompromising, and seemingly unending.”

In a journal article for Foreign Affairs, Mr Rudd writes there are now real fears about what happens next.

“The question now being asked, quietly but nervously, in capitals around the world is, where will this end?,’’ Mr Rudd writes.

“The once unthinkable outcome — actual armed conflict between the United States and China — now appears possible for the first time since the end of the Korean War. In other words, we are confronting the prospect of not just a new Cold War, but a hot one as well.”

Mr Rudd said that Beijing and Washington should reflect on the admonition “be careful what you wish for”.

“If they fail to do so, the next three months could all too easily torpedo the prospects of international peace and stability for the next 30 years. Wars between great powers, including inadvertent ones, rarely end well — for anyone,’’ he said.

RELATED: China hits back at Australia-US statement on South China Sea, Hong Kong

Mr Rudd, 60, has enrolled as a PhD student at Oxford University and is working on a doctorate focused on Chinese president Xi Jinping.

He writes that the pressures of domestic politics in the United States in the lead up to the election could now heighten tensions with China.

“While Xi’s strategy has been clear, Trump’s has been as chaotic as the rest of his presidency,’’ he writes.

“But the net effect is a relationship stripped of the political, economic, and diplomatic insulation carefully nurtured over the last half century and reduced to its rawest form: an unconstrained struggle for bilateral, regional, and global dominance.

“The risks will be especially high over the next few critical months between now and the November US presidential election, as both US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping confront, and exploit, the messy intersection of domestic politics, national security imperatives, and crisis management ,’’ he said.

“Political opinion in both countries has turned toxic. The list of friction points is long, from cyber-espionage and the weaponization of the dollar to Hong Kong and the South China Sea.

RELATED: South China Sea: Australian warships reportedly ‘confronted’ by Chinese navy

RELATED: South China Sea: US clash with China now ‘inevitable’

“China has become central to the race like never before. It now frames presidential politics across nearly all major campaign issues, including the origins of COVID-19 and the United States’ disastrous response, which, as of mid-2020, has left more than 150,000 Americans dead; an economic crisis marked by 14.7 per cent unemployment, a 43.0 per cent rise in bankruptcies, and eye-watering public debt; not to mention the future of American global leadership.”

Mr Rudd notes that President Trump’s “heated rhetoric has been matched by actions on the ground.”

“US military forces, for example, have begun responding more forcefully to Chinese actions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait,’’ he said.

“Meanwhile, Trump’s opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden, is determined not to be outflanked by Trump on China, making for a uniquely combustible political environment. That leaves little room for foreign policy nuance, let alone military compromise, should any crisis arise.”

The South China Sea looms as a clear danger zone, particularly after Australia’s tougher stance on China’s claims in the region.

“The South China Sea has thus become a tense, volatile, and potentially explosive theatre at a time when accumulated grievances have driven the underlying bilateral political relationship to its lowest point in half a century,” Mr Rudd writes.

“The question for both US and Chinese leaders is, what happens now in the event of a significant collision?

“If an aircraft is downed, or a naval vessel sunk or disabled, what next steps have been agreed in order to avoid immediate military escalation?”