Inside Beijing’s mixed messages after threatening armageddon against the US and missile strikes on Australia

Last month, a CCP member warned of an “intense showdown between China and the US”. Days later, Xi Jinping delivered a baffling message.

China has gone “thermonuclear” – threatening armageddon against the United States and missile strikes on Australia.

But now, Chairman Xi Jinping is suddenly demanding “trustworthy, loveable and humble” diplomacy.

Beijing’s brand of statecraft isn’t based on subtle signalling. But threatening a nuclear firestorm was previously the personal domain of North Korea’s tyrannical Kim Jong-un.

“It is one thing to deal with a power that has a clear goal; one might be at cross-purposes, but at least one knows where matters stand. A power lashing out like a belligerent drunk, however, is more difficult to address,” warns professor of Chinese foreign relations Sulmaan Wasif Khan.

And Beijing’s messaging is certainly belligerent.

“We must be prepared for an intense showdown between China and the US,” Global Times news service executive editor Hu Xijin wrote.

“The number of China’s nuclear warheads must reach the quantity that makes US elites shiver should they entertain the idea of engaging in a military confrontation with China.”

That’s not the voice of a fringe columnist desperate for attention.

RELATED: Mystery grows as Kim vanishes

They’re the considered words of a ranking Communist Party member broadcast in a political environment which automatically censors even potentially critical terms such as “Pooh Bear” and “emperor”.

That was Thursday, May 27.

Three weeks earlier, on May 7, Hu similarly menaced Canberra: “China has a strong production capability, including producing additional long-range missiles with conventional warheads that target military objectives in Australia when the situation becomes highly tense.”

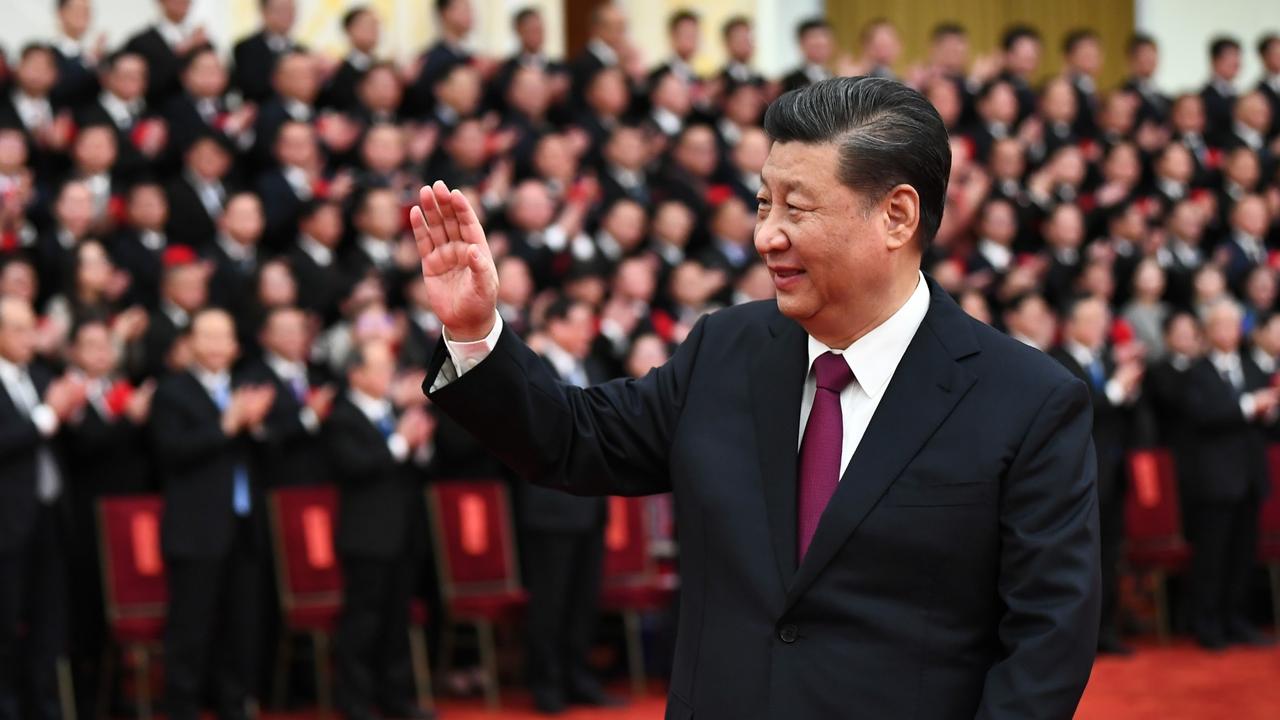

Then, on Tuesday, June 1, Chairman Xi Jinping stood to speak at a gathering of the Chinese Communist Party’s most elite of elites – the Politburo.

The 24 party faithful “listened carefully to his explanation and discussed it”.

Xi proclaimed an urgent need to “create a favourable external public opinion environment”.

“We must pay attention to grasp the tone, be open, confident and humble, and strive to create a credible, loveable, and respectable image of China.”

Fire and fury

“I would like to remind again that we have plenty of urgent tasks, but among the most important ones is to rapidly increase the number of commissioned nuclear warheads,” Hu wrote of China’s growing nuclear capability.

He pointed, in particular, to the new DF-41 strategic missiles that are capable of reaching most of the world and said to be capable of dodging most attempts to intercept them.

“This is the cornerstone of China’s strategic deterrence against the US,” he states.

“A large number of Dongfeng-41, and JL-2 and JL-3 (submarine-launched ballistic missiles), will form the pillar of our strategic will.”

The next day, May 28, one of his staff penned another threat.

This time again aimed at Australia.

“Zhang Junshe, a senior research fellow at the PLA Naval Military Studies Research Institute, (said) Australia is likely to allow the US to deploy more military equipment on its soil, making it the only US friend on its Indo-Pacific strategy,” the story states.

“By doing this, Australia will make itself a target for future military conflicts between the US and other countries.”

At the moment, China’s nuclear stockpile is considerably smaller than that of the United States: some 200-300 warheads against 5800.

But it is considerably more modern. And flexible.

And that puts China at significant risk of escalation.

The DF-26 “Carrier Killer” intermediate-range ballistic missile can carry either conventional or nuclear warheads. So knowing precisely what has been fired your way will be of extreme importance if a conflict eventuates.

“We must use our strength, and consequences that Washington cannot afford to bear if it takes risky moves, to keep them sober,” Hu declared.

Wolf-warriors muzzled?

Chairman Xi’s call for a new international image came at a new low in Beijing’s growing feud with Washington and the West.

President Joe Biden last week ordered his intelligence agencies to “double-down” on their investigations into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic in the face of China’s resistance.

Beijing’s diplomats – renowned for their hypersensitivity to criticism – lashed back, calling the move divisive, racist, and unscientific. Its Wolf Warriors (outspoken diplomats) once again attempted to shift the blame back on the US itself – reviving allegations the virus came from Fort Detrick in the US.

And Hu’s thermonuclear threat was published the day after President Biden’s address.

But was it a howl too far?

Beijing knows its diplomacy is on the nose.

An international survey last year of 14 nations across Europe, North America and Asia found China increasingly unpopular. And this was also the case before allegations began to fly that Beijing had attempted to cover up the opening stages of the pandemic in Wuhan province.

And that’s because of its Wolf Warrior diplomacy.

Its repression of the Uighur ethnic minority. Its aggressive attitude towards Taiwan and Hong Kong. Its incursions into territories claimed by India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Japan.

RELATED: PM’s ‘grave error’ with China: Albanese

Little wonder that, combined with the belligerence of its diplomats, Beijing isn’t all that popular.

So do Xi’s seemingly moderate words indicate a policy shift?

International experts aren’t so sure.

And, on Wednesday, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Wang Wenbin dodged a question asking if his diplomats would be changing their tone.

So what do Xi’s words mean?

Are they an admonition of an overly-enthusiastic but patriotic Communist Party branch?

Or do they translate to “The West must be persuaded to see things China’s way”?

Lost in translation?

After Chairman Xi’s Politburo appearance, state-controlled media immediately jumped to the task. “Xi’s warm moments with children” suddenly featured on the People’s Daily YouTube channel.

Was it a sign of things to come?

In 2016, Chairman Xi ordered a major shift in Chinese diplomatic posture.

He demanded a “dare-to-fight” spirit to advance Chinese interests forcefully.

This undid decades of Communist Party leadership enforcing a focused – but moderate – international front.

Last year, it got worse. Much worse.

“What changed in 2020 was that nationalism for its own sake became the predominant motif of Chinese conduct,” writes Professor Khan.

“From that year on, what stands about China’s diplomacy is spreading wild rumours about Covid-19, getting in a shouting match with Australia, and threatening dire consequences for anyone who opts to boycott the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing”.

He accuses Beijing – and Chairman Xi – of dropping the ball.

“The predominant feature of Chinese conduct today is not grand strategy but a belligerent, defensive nationalism that lashes out without heed of consequences. Just why that breakdown has occurred is uncertain, but it is clear that the change has put both China and the world in jeopardy.”

But the answer, one analyst argues, is staring us in the face.

“What really drives China’s economic statecraft is not grand strategic designs or autocratic impulses but something more practical and immediate: stability and survival,” says Harvard and MIT securities studies researcher Audrye Wong.

“The Chinese Communist Party’s fundamental objective is to preserve the legitimacy of its rule. China’s economic statecraft, then, is often employed to put out immediate fires and protect the CCP’s domestic and international image. China wants to stamp out criticism and reward those who support its policies.”

Between the lines

Even as Chairman Xi made the placatory pronouncements, his generals were busy encouraging the opposite.

Three warships pushed into waters around Japan in the wake of its military exercises with the US, France and Australia. The Global Times contradicted itself by declaring the voyage “routine” and that it “should be considered a warning to Tokyo”.

Which is also odd, as, on April 20, Chairman Xi had warned against “bossing others around”.

“International affairs should be conducted by way of negotiations and discussions, and the future destiny of the world should be decided by all countries,” Xi told the Boao Forum for Asia.

“However strong it may grow, China will never seek hegemony, expansion or a sphere of influence, nor will China ever engage in an arms race.”

But his maritime militia remains in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. And, on Tuesday, a force of 16 modern Chinese military aircraft entered airspace under the control of Malaysia – eliciting a fierce diplomatic protest.

RELATED: Fears over China’s stake in Aussie port

All after Xi called for a change to China’s diplomatic stance.

But exactly what kind of change?

“It is necessary to strengthen top-level design and research layout, build a strategic communication system with distinctive Chinese characteristics,” he said, “and focus on improving international communication influence, Chinese cultural appeal, Chinese image affinity, Chinese discourse persuasiveness, and international public opinion guidance”.

“It is necessary to strengthen the propaganda and interpretation of the Communist Party of China, to help the foreign people realise that the Communist Party of China really strives for the happiness of the Chinese people, understand why the Communist Party of China can, why Marxism is practised, and why socialism with Chinese characteristics is good.”

Words can wound

“There is no obvious point to it,” Professor Khan says of Beijing’s “thermonuclear” diplomacy.

“It was completely pointless for Foreign Ministry spokespeople Zhao Lijian and Hua Chunying to tweet conspiracy theories about Covid-19 or for China to launch a trade war with Australia simply because the Australians had the gall to call for an investigation of China’s handling of the pandemic. These are knee-jerk reactions, bereft of the cool manoeuvring that defines grand strategy.”

This, he says, could be symptomatic of patriotism – weaponised in the face of independence moves from Hong Kong and Taiwan – breaking loose from Chairman Xi’s control.

“There is no attempt to rein these fits of temper in. Worse, it seems likely that even if they were issued, they would be difficult to enforce, with purposeless nationalism now run amok.”

It’s a position doing immense damage to China’s international reputation.

And stepping down won’t be easy for an autocrat to do.

It would require an easing of repressions in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. It would need a new state of mutual understanding with Taiwan. It would involve a full and free investigation into Covid-19.

“A tall order, but it would put China on a more stable footing, cut costs, and win friends,” Khan says.

“Short of all this, even simply backing off the most strident rhetoric, ceasing disinformation campaigns and easing up on activity in the Taiwan Strait would save money and make it harder for the rest of the world to sustain a hostile posture toward China.”

And the rest of the world must take heed of the damage Beijing’s belligerence has inflicted upon itself.

“When competing, it should be done quietly,” Khan says.

“Chest-thumping or forceful statements elicit similar responses in Beijing and rarely do much good.

“A policy like this will not turn China into a peace-loving democracy. But it would deprive the wolf warriors of attention, which is what they seek in the first place.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel