How China stands to benefit from end of Afghanistan war

As Australia and the US exits, China is moving in on the troubled country to execute an ambitious plan to expand its own interests.

The Afghanistan war is over. We lost. The Taliban is advancing. The troops Australia spent decades training are in full retreat. And China’s ready to pounce.

As the Western world “pivots” its attention to Southeast Asia and the growing aggressiveness of China, the war on terror in Afghanistan has lost its appeal.

Military analysts fear the total rout of demoralised Afghan security forces in the north of their country at the weekend is a sign of things to come.

Just days earlier, the United States cleared its main headquarters facility at Bagram Air Base. Their withdrawal is expected to be completed by September 11.

Australia evacuated the last of its troops – after 20 years and 41 lives – from Afghanistan in June.

The Taliban is not attacking retreating Western forces. Instead, it waits for them to move out. Then it moves in. It has already seized control of much of the northern province of Badakhshan, bordering Tajikistan and China.

And that’s Afghanistan’s curse.

Amid the upheaval and civil convulsions, one thing about the nation won’t change.

It occupies the strategic crossroads between Europe, Asia and India.

And Beijing knows it.

RELATED: 50,000 troops rushed to China border

Unstrapping the belt

There’s a reason why the Chinese Communist Party is so determined to completely subdue the Islamic Uighur people in the western province of Xinjiang. It’s a strategically crucial fork in their “Belt and Road” trade plan with Europe.

So is neighbouring Afghanistan.

Beijing has already proposed a $US62 billion investment in Kabul. It on the arterial China-Pakistan Economic Corridor of roads, railways, pipelines and cables.

China, Afghanistan and Pakistan met via video conference last Thursday to discuss the project – and the “security situation”. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi says the three countries “needed to strengthen communication and co-operation” to advance Afghanistan’s interests.

And China’s.

“There is a discussion on a Peshawar-Kabul motorway between the authorities in Kabul and Beijing,” an anonymous Afghan government source reportedly told The Daily Beast.

“Linking Kabul with Peshawar by road means Afghanistan’s formal joining of CPEC.”

It may also be a lifeline for the beleaguered Afghan government.

RELATED: ‘Startling find’ deep in Chinese desert

Such an enormous investment comes with masses of Chinese supervisors, advisers and labourers. And these will need protection.

“Ghani needs an ally with resources, clout and ability to provide military support to his government,” the official said.

Such an alliance is feasible.

Beijing, however, is hedging its bets. It has also been in talks with the Taliban itself. It has reportedly been offered infrastructure, cash and a “welcome back to the political mainstream” – in exchange for peaceful passage.

But the weight of history suggests it won’t be an easy ride.

“The security and stability of Afghanistan and the region are facing new challenges, with foreign troops’ withdrawal from Afghanistan accelerated, the peace and reconciliation process in Afghanistan impacted, and armed conflicts and terrorist activities becoming more frequent,” Wang said.

The weight of history

“Another great power afflicted with hubris comes to grief in the graveyard of empires,” writes former UN assistant secretary-general and emeritus professor at the Australian National University Ramesh Thakur.

In April, he predicted “the US will complete an inglorious withdrawal, and the exodus of its allies will be all exit and no strategy.”

The exit isn’t quite over yet. But the lack of strategy is apparent. And that’s nothing new.

Afghanistan has a history of bringing great powers low.

Babylon’s Darius I. Alexander the Great of Macedonia. Both seized it. Neither could hold it for long.

The British Empire tried – and failed – to annex it in 1838. They gave up in 1921.

The Soviet Union tried to seize it as a buffer in 1979. Instead, it withdrew its 100,000 troops in 1989.

In 1995, the Taliban – grown rich on the illegal opium trade – took control.

Sharia law was enforced. Executions and amputations were conducted in the streets. Women and girls were banned from work and education.

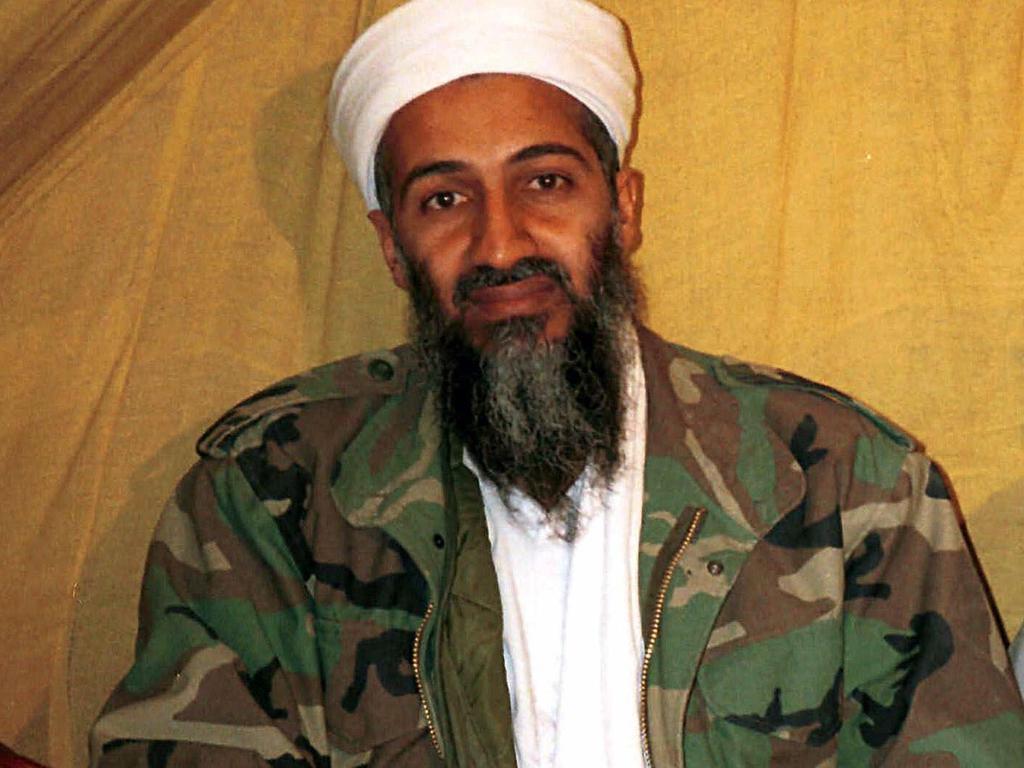

Terror group al-Qaida and its leader Osama bin Laden found a group of friends they could operate safely among. That’s what triggered the occupation of Afghanistan by the US and its allies in 2001, after the September 11 attacks.

Afghanistan’s former president Hamid Karzai, who took on his role after the 2001 invasion, has called the withdrawal a “total disgrace and disaster”.

“The (US/NATO military) campaign was not against extremism or terrorism. The campaign was more against Afghan villages and hopes, putting Afghan people in prisons, creating prisons in our own country … and bombing all villages. That was very wrong,” he said.

Now, it may be Beijing’s turn to get mired by history.

China has always been uneasy at the presence of US and allied military forces on its borders. But it’s also worried about the region being a haven for insurgents. This is why it has already been working with Tajikistan and Pakistan on a crackdown on Turkic ethnic groups.

That was a central tenet of last week’s three-nation talks.

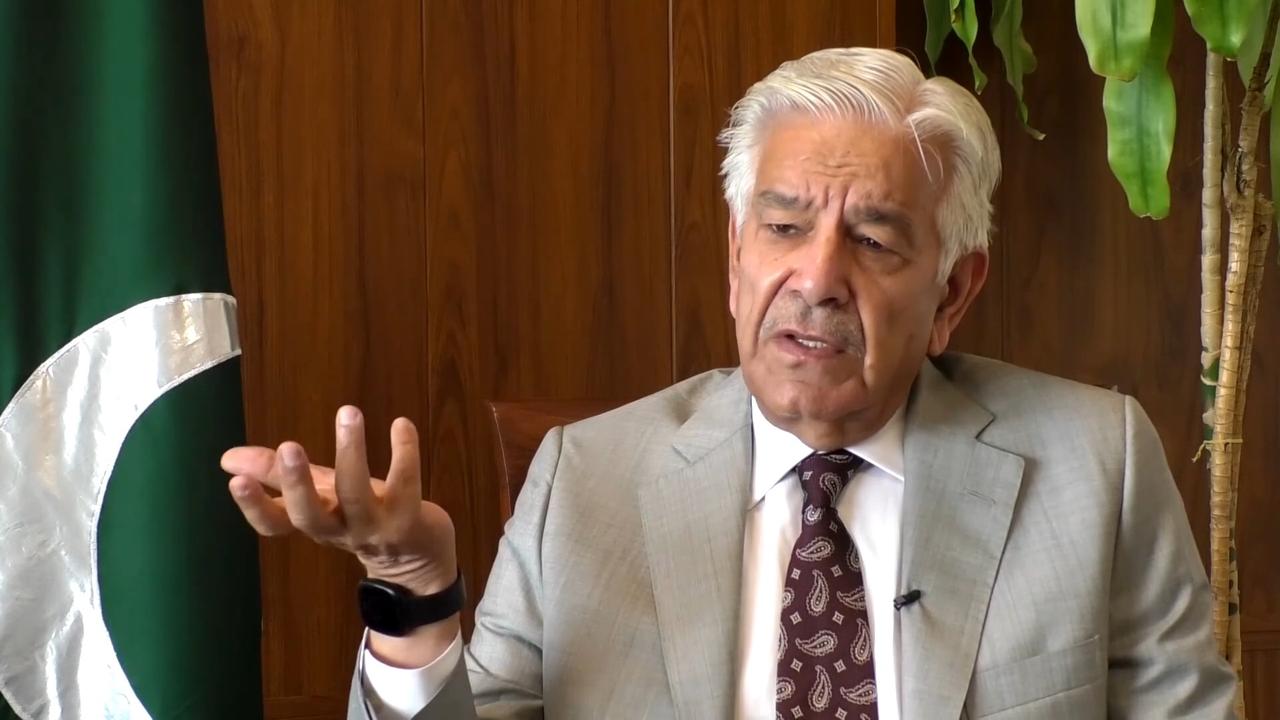

Wang, Afghan Foreign Minister Mohammad Haneef Atmar and Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi “stressed the need to … forbid any terrorist organisations or individuals from using their territories to engage in criminal activities against other countries.”

That means the Uighurs. Not so much the Taliban.

Trillion-dollar tragedy

“Was it worth it? Well, as we face the prospect of a savage retribution by the now ascendant Taliban, and I think a return in some ways to the dark ages for Afghanistan — it’s really hard to say that it was worth it,” retired Lieutenant General Peter Leahy said.

Afghanistan’s former president Hamid Karzai was more direct.

“The international community came here 20 years ago with this clear objective of fighting extremism and bringing stability … but extremism is at the highest point today. So they have failed,” he said.

The United States, backed by NATO and allies including Australia, went into Afghanistan after September 11. Their mission? Undefined.

Washington sank 100,000 US troops into the enterprise at an annual cost of $US100 billion.

The last 3000 troops and 7000 allied NATO forces are already on their way out.

At its peak, the Australian Defence Force had committed 1550 special forces and soldiers. The final group of 80 advisers and trainers were flown out last month.

“After 20 years of Western blood and treasure, no one seriously expects the Afghan government and army to be fit for purpose against the Taliban,” Thakur declared.

Some 25,000 Taliban fighters managed to hold out in their mountain caves for more than two decades. Now they’re free to impose their extreme interpretation of scripture on a terrified populace once again.

Washington says it will continue to support the Afghan government and people.

The promise is to help in counter-terror operations from “over the horizon”.

But the airspace over Afghanistan may soon become crowded with Chinese drones, helicopters and combat jets if their expanding interests are threatened.

And then, almost inevitably, will come the troops. Again.

“The only answer is Afghans getting together … We must recognise that this is our country, and we must stop killing each other,” Karzai concludes.

“We will be better off without their military presence.

“I think we should defend our own country and look after our own lives. … Their presence (has given us) what we have now. … We don’t want to continue with this misery and indignity that we are facing. It is better for Afghanistan that they leave.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel