China’s desert nuclear missile silos not a threat to western powers

Satellite photos have revealed a dramatic nuclear plan by China. The move threatens the power balance between East and West.

Beijing is building fear. Satellites have discovered a second field of nuclear missile silos being dug in a Chinese desert. It’s no accident they’ve been seen. That’s the whole point.

China’s People’s Liberation Army has begun boosting its small force of 20 or so intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos to about 250. At least that’s as many new sites the West is aware of so far.

RELATED: China threatens to nuke Japan

It’s a dramatic increase in its nuclear arsenal. It’s a significant shift in posture.

“It would be a nuclear force strong enough to make the US – from the military to the government – fear,” an unattributed editorial in Wednesday’s Global Times asserts. “Equilibrium will be achieved when … the US completely loses the courage to even think about using nuclear weapons against China, and when the entire US society is fully aware that China is untouchable in terms of military power.”

Bates Gill, professor of security studies at Macquarie University and Senior Associate Fellow with the Royal United Services Institute in London, says “untouchable” is the keyword.

“Does this mean China wants to fight a nuclear war? Absolutely, not,” he says. “The last thing it wants is a nuclear exchange. This – in China’s mind – is a way of stopping others from using nuclear weapons against it.”

As Beijing transitions to a more robust arsenal, Professor Gill believes the risk of a nuclear incident is increased. But the likelihood of such a conflict will fade as China’s nuclear deterrent grows.

All the while, though, the twisted logic of mutually assured destruction (MAD) makes the odds of a conventional arms clash all the more likely.

“What this really means for us is not the threat of nuclear war,” Prof Gill says. “What it means is China feels more confident in engaging in a conventional war. Because they’re not going to be deterred by the possibility of nuclear escalation. And, increasingly, they believe they can win.”

Lines in the sand

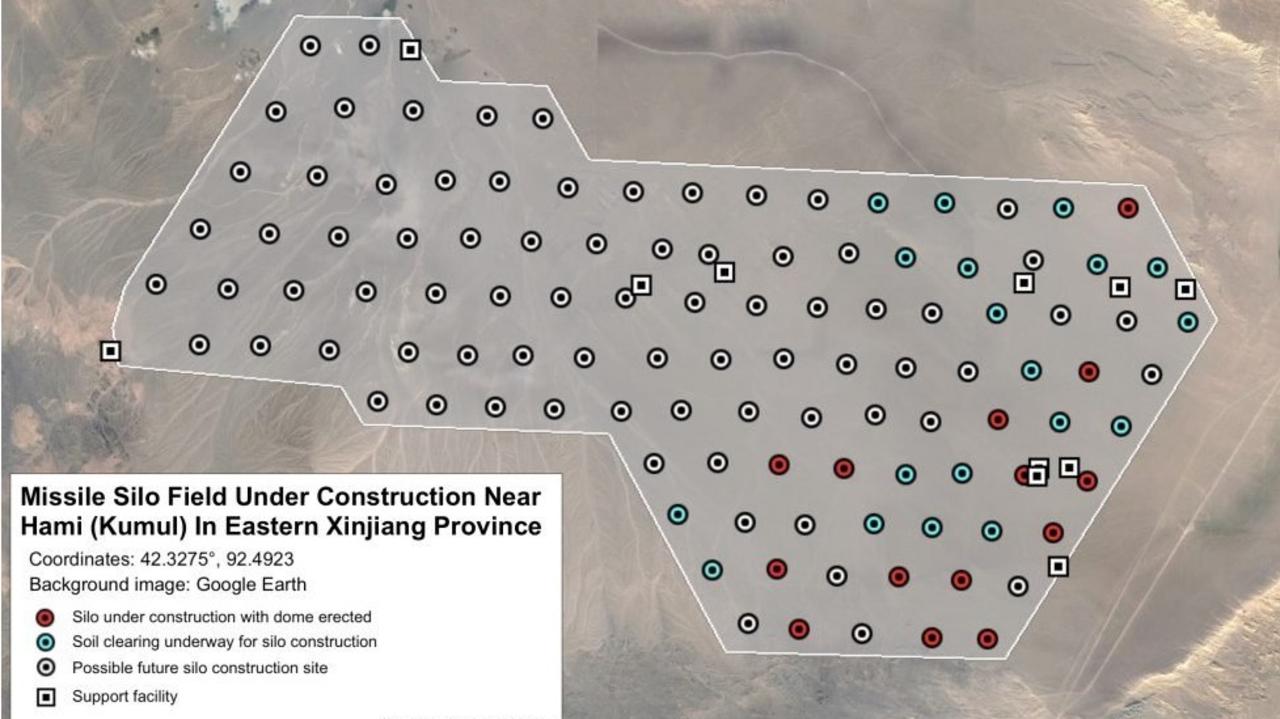

The Federation of American Scientists has discovered a new Chinese nuclear missile silo construction site – the second in the space of a month.

It’s near the remote Xinjiang Province city of Hami. It’s about 400km northwest of Yumen, in Gansu Province, where the first site was found.

RELATED: Satellites expose China’s ICBM explosion

So far, 14 prefabricated domes have been built to conceal new silo sites in a flat, dry salt pan. Preparation works have begun on 19 others. And a series of 11 support facilities are being scattered across an 800 square kilometre area.

Extrapolate a staggered pattern between these facilities, and there’s enough room for a total of 110 new silos. That’s just 10 fewer than the total at Yumen.

“It alters the current calculus, no doubt about it,” Prof Gill says.

But he adds it’s not the threat it immediately appears to be.

“Just one nuclear weapon hitting the soil of the United States – or anywhere for that matter – incurs a price far too high to pay,” he says. “Nobody wins. China understands that. It’s been understood since day one.”

Instead, it’s about Beijing “shifting the battlefield” to an arena where it can win.

“China wants to hold the US at risk so that it won’t launch a nuclear attack. But up until about 10 years ago, Beijing didn’t feel confident it could guarantee retaliation in response to a nuclear strike. Now that retaliatory deterrence is more fully formed, even more so if this recently discovered set of developments proceeds.”

Offensive defence

A handful of small, “tactical” thermonuclear warheads could stop an invasion of Taiwan in its tracks. If it had no nuclear weapons of its own, Beijing could not do anything about this.

But the prospect of nuclear retaliation is a powerful deterrent. As is the threat of escalation.

That’s the fear Beijing seeks to impose.

“What this does is push any likely field of battle – with the US and others like India and Russia – down to the conventional realm,” says Prof Gill.

An expanded force of missile silos, mobile truck-mounted ICBM launchers, missile submarines, and stealth bombers will give Beijing confidence it can strike back.

“It believes it can deter nuclear threats. It can deter nuclear blackmail,” he says. “Beijing is becoming confident they can manage a nuclear war in a way so that it doesn’t happen.”

Where China is increasingly confident they can succeed, however, is in the arena of conventional weaponry, and especially advanced missiles.

Its navy is now the world’s largest. And it’s rapidly expanding the quality and quantity of everything from aircraft and tanks to submarines and aircraft carriers.

“And its new nuclear force makes Beijing confident any conflict won’t escalate to the nuclear level where China would lose big time,” Prof Gill adds. “That, I think, is the ultimate motivation.”

That has implications for what Beijing calls its’ sphere of strategic interests – the South and East China Seas, Taiwan and the Himalayas.

“Beijing thinks ‘we can beat you in that sphere – and one reason we can is that you will not escalate to nuclear’.”

Moments of transition

“In the perverse and cruel logic of nuclear deterrence, we’re actually in some ways headed towards a more stable world,” says Prof Gill. “We will be deterred.”

Nuclear powers such as the United States, India, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, Pakistan and Israel will face mutually assured destruction if they use nuclear weapons against China.

“But I think the transition period is where there’s a greater likelihood for instability. And that’s where we are right now.”

Having so many ICBM silos means more than playing a game of “whack-a-mole” when it comes to trying to destroy the warheads they may – or may not – contain.

It also gives Beijing the scale needed for a “launch on warning” alert status.

That means having enough missiles for some to be always primed, loaded and ready to go at an instant’s notice.

Such a rapid reaction time can guarantee mutually assured destruction.

But it could tempt a surprise first strike.

“Beijing will still argue that they will not fire unless fired upon,” Prof Gill says. “But it gives them options. It also magnifies mistakes.”

He was referring to the 1983 “Able Archer” NATO exercise that almost accidentally triggered a nuclear conflict with the Soviet Union. Every step along the nuclear launch chain underwent simulation. But Moscow initially believed it was a ruse concealing an actual first strike.

Response times now are much faster.

The opportunities to realise such mistakes have contracted.

Prof Gill says this raises the “always never” problem.

“The always never problem is ensuring your nuclear weapons will always go off when you want them to – and they will never go off when you don’t want them to,” he says.

Prof Gills asks, “In a crisis or conflict, how does Beijing delegate authority to nuclear force commanders on land and at sea? What if they can’t contact the supreme command in Beijing in a crisis? What if that supreme command has been eliminated? That’s a really complicated command and control problem that they now have to figure out.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel