China-India border skirmish: 155-year-old map fuelling dispute

Gruesome scenes last week, with troops bludgeoned to death, are just the latest skirmish in a seething dispute going back a century or more.

High in the icy cold and barren Himalayas, not a shot was fired last week – and yet possibly as many as 60 soldiers from China and India died.

Gruesome accounts have emerged of troops attacked with rocks and nail studded clubs and then left to freeze to death.

It was the single deadliest clash between the two nuclear armed neighbours in six decades.

But while the clashes are recent, their root lies in a series of maps, the first of which was drawn up as far ago as 1865.

British surveyor WH Johnson can't have imagined the deadly echoes that would ricochet through the years of his journey into the mountains.

In recent days, both sides have tried to clam tension. Nevertheless, China has warned India “don’t push us” following the brutal battle. While, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said the deaths "will not be in vain". Pictures of Chinese President Xi Jinping have been burned on the streets of Indian cities.

“I’m surprised by the scale and the number of causalities, but I’m not surprised by these kinds of incidents occurring – they happen from time to time,” Associate Professor Jingdiong Yuan from Sydney University’s China Studies Centre told news.com.au.

‘BODIES BRUTALISED’

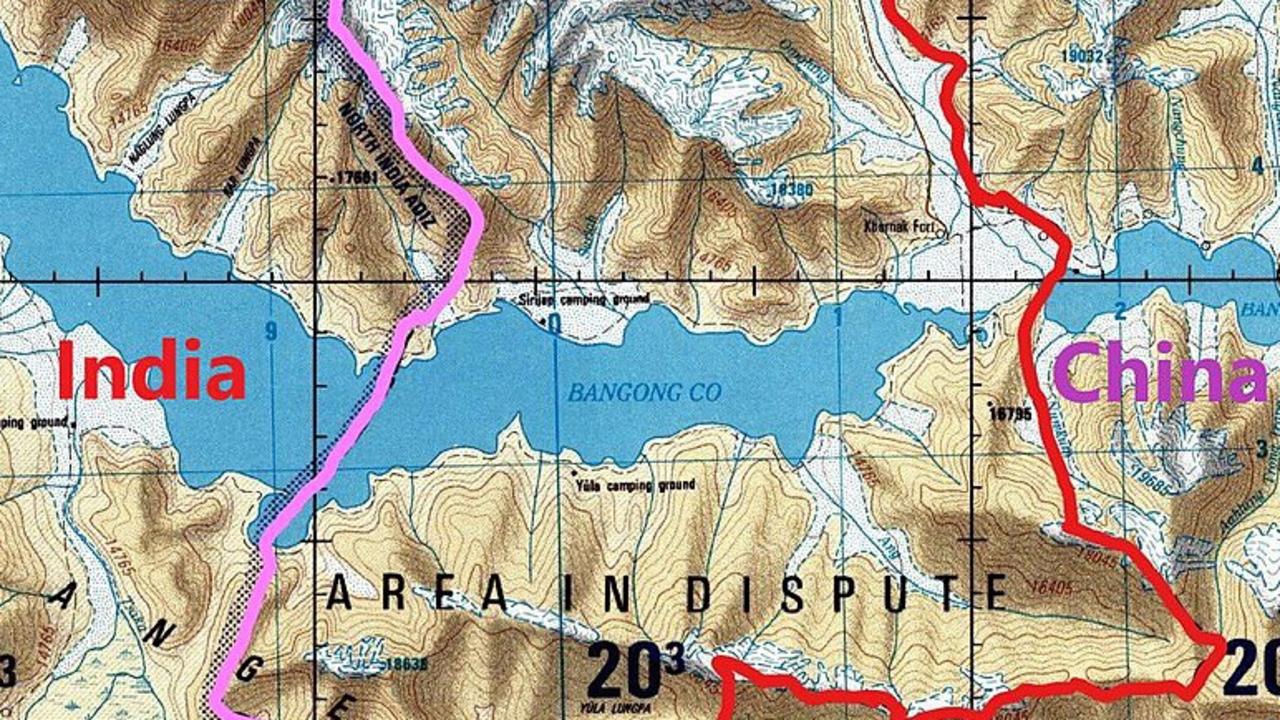

Monday’s fracas occurred in the Galwan Valley close to what is known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), a demarcation line between the two regional heavyweights. It divides India’s Ladakh region from the Chinese governed Aksai Chin region.

“An argument started over the position of Chinese soldiers who had started erecting a new post on the southern bank of Galwan river in this buffer zone,” reported the Indian Express.

“When the commanding officer and his troops insisted that the Chinese remove the post, the situation quickly escalated.

“The Chinese side, officers said, used sticks, clubs, bats, bamboos with nails during the fight and the Indian side too retaliated.”

“Some bodies had signs of being brutalised. A few soldiers died of hypothermia.”

The remote nature of the terrain makes it difficult to verify the accounts. India has been more detailed with its version of events and has said at least 20 of its soldiers died.

China has said little about the substance of the skirmish but India has claimed at least 40 Chinese soldiers were killed, claims that China has not denied. China reportedly released 10 Indian soldiers it captured on Friday.

STICKS, STONES … BUT NO SHOTS

An intriguing detail no one is disputing is the fact no shots appeared to have been fired.

“That there were no causalities by firearms seems due a conscious decision by both sides that when they do send patrol units (to the frontier) they typically don’t carry guns,” said Prof Yuan.

“That’s even though in recent months they have mobilised heavy equipment close to the border.”

A 1996 agreement by China and India regarding border patrols in the area states, “neither side shall open fire within two kilometres from the LAC”. While the agreement’s aim may have been to avoid bloodshed, it didn’t work.

Many agreements, meetings, skirmishes and one all out war have been fought over the frontier, the site of which was first proposed in 1865.

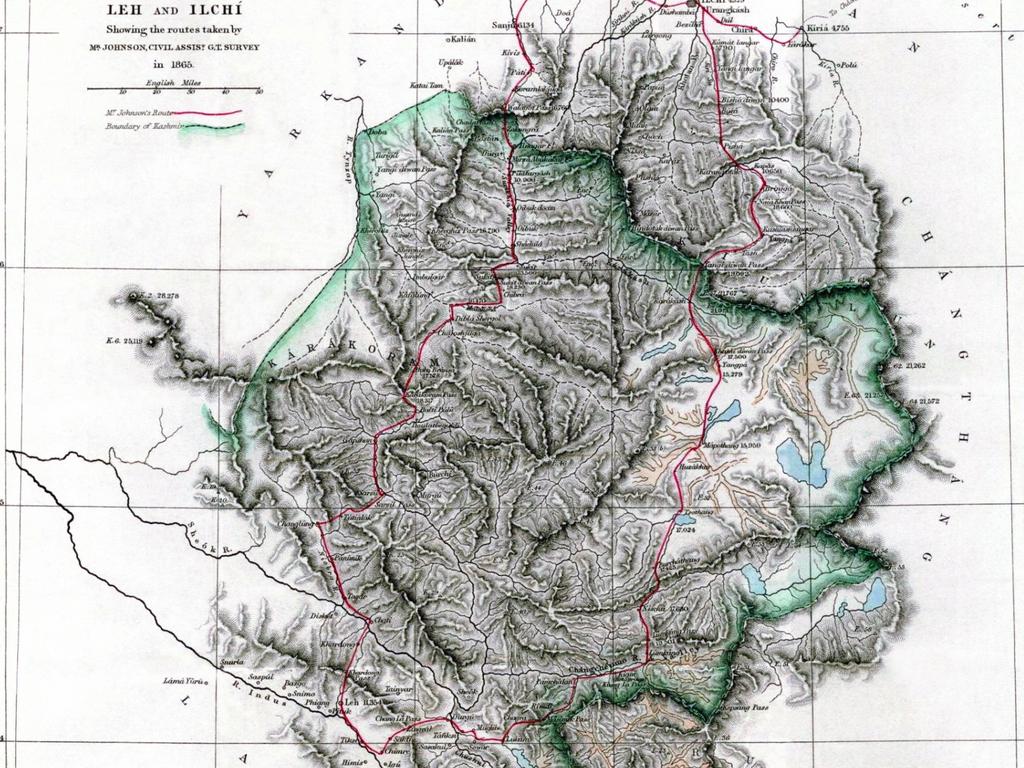

JOHNSON’S 1865 MAP

The Himalayas provides a natural border between nations – but not a very specific border. With no settlements, it’s hard to know where India ends and China begins.

In the 1860s William Johnson – a surveyor from British-colonised India – set out to map the sparsely populated region of Kashmir. This was a princely Indian state and the expedition headed from there towards Tibet and what is now the Chinese province of Xinjiang.

Johnson’s survey proposed a northern boundary for Kashmir and in 1897 this was formalised as the Ardagh-Johnson line. It placed all of Aksai Chin within British India.

To confuse matters, other British planners came up at various times with other boundary lines. Some, like the 1899 Macartney-MacDonald line, were less ambitious and would have seen split Aksai Chin. However, China was said never to have responded to that proposal, so versions of Johnson’s map became Britain, and then independent India’s, fallback position.

Neither Britain nor India put much effort to assert control or place border posts in these remote regions. So much so that it took years for India to realise in the 1950s that China had actually built a 1200 kilometre road right through what was ostensibly its territory.

In 1962, thousands of Indian and Chinese soldiers died when the two nations went to war over the frontier. The LAC, more of a ceasefire line than an border, was established in the aftermath. But it wasn’t a good outcome for India as it put all of Aksai Chin under Chinese control.

THE “GREY ZONE”

Today, India and China still claim large chunks of each others territory, both around Kashmir and in the east with China laying claim to much of India’s Arunachal Pradesh state.

“They have been negotiating for a very long time you but they cannot come to an agreement about where they should start to demarcate the boundary,” said Prof Yuan.

This fuzziness has led some to call it the “grey zone”. Even the LAC itself is hard to pin down with even the two nations having different ideas of its location.

“There’s no markers and weather conditions and snow can make it very difficult to delineate exactly where the line is, so patrols can stray onto the other side,” said Prof Yuan.

“This is a very long border area, 3500 km from west to east, and pockets of it are considered by both sides to be very strategic with pathways and elevations they are keen on getting an advantage over.

“Both sides are now building up more infrastructure, roads and military installations, so there are more personnel in the grey zone and inevitably the frequency of encounters are increasing, as are the chances of conflict.”

In 2013 and 2017, the pair came to blows when China began building roads and established bases close to India. This time around, it was a new Indian road that sparked Beijing’s ire.

INDIA HAS THE “UPPER HAND”

A study by US think tank the Belfer Centre said India was in pole position despite China’s undoubted military muscle. It had more war planes and they are stationed closer to the conflict zone, reported CNN. China has a similar number of soldiers in the region, but its jets are less stealthy and its bases further away. Indian troops also had more combat experience given its skirmishes with Pakistan.

“India has the upper hand in terms of their mountain positions and their soldiers might be better acclimatised to those areas so are better prepared than the Chinese,” said Prof Yuan.

“The Chinese have better logistics and an ability to aggressively move troops. China spends four times more on defence but India has the local balance of power.”

NUCLEAR FEAR

The real fear, given both have stockpiles of nuclear missiles, is if the mountain melees trigger a hotter conflict.

“They both run the risk of massive casualties, in a conventional military conflict and one that could escalate to nuclear,” said Prof Yuan.

But Prof Yuan said the realisation that things could get a lot worse may have actually encouraged sense to prevail.

Since the bloodbath there have been statements from both sides attempting to calm nerves and assurances a similar gruesome meeting will not be repeated.

Although, the statements are somewhat snippy.

"India wants peace but when provoked, India is capable of giving a fitting reply, be it any kind of situation,” Mr Modi said.

China’s Global Times newspaper, Communist Party mouthpiece, struck a similar note.

“The two sides agreed to fairly deal with the serious clashes between Chinese and Indian troops and … to cool the situation down. China is committed to friendship with India.”

Then came the but.

“China resolutely defends its territorial sovereignty. India should never think about pushing China to make concessions, because China won't.”

Prof Yuan said it was remarkable that despite the frontier face-offs, China and India continue to co-operate in other areas such as trade.

“The silver lining is nether side is holding their bilateral relationship hostage to a territorial dispute.”

But he said the two needed to better control their troops.

“Tempers flared in the moment. Something terrible happened here when they should have been disengaging. They have to manage these situations so they don’t spill into other areas.”

As the Global Times stated: “The border is the most sensitive part of China-India relations. Only when it is eased can the two engage in co-operation in a composed manner. ”