3D printed F-35 simulators part of multi-billion bid to cut costs for JSF

EACH one of the new fighter jets is worth almost $100 million and finding a cheaper way to train pilots could shave billions off the cost of the program.

AUSTRALIAN fighter jet pilots could be learning to fly in 3D printed cockpits by 2020.

The technological innovation has been revealed by Lockheed Martin as part of a broader, multibillion-dollar bid to rein in costs for the trillion-dollar F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program.

It comes as the US corporation announced they would add a cheaper, new computer processor to both cut back on expenses and enhance the jet’s impressive list of capabilities in the future.

RELATED: F-35 Lightning II: The iPhone of fighter jets is world’s most lethal

Australia has a $17 billion order for 72 of the fifth-generation fighter jets, though the global cost of the JSF program across the coming decades is tipped to cost $1.1 trillion.

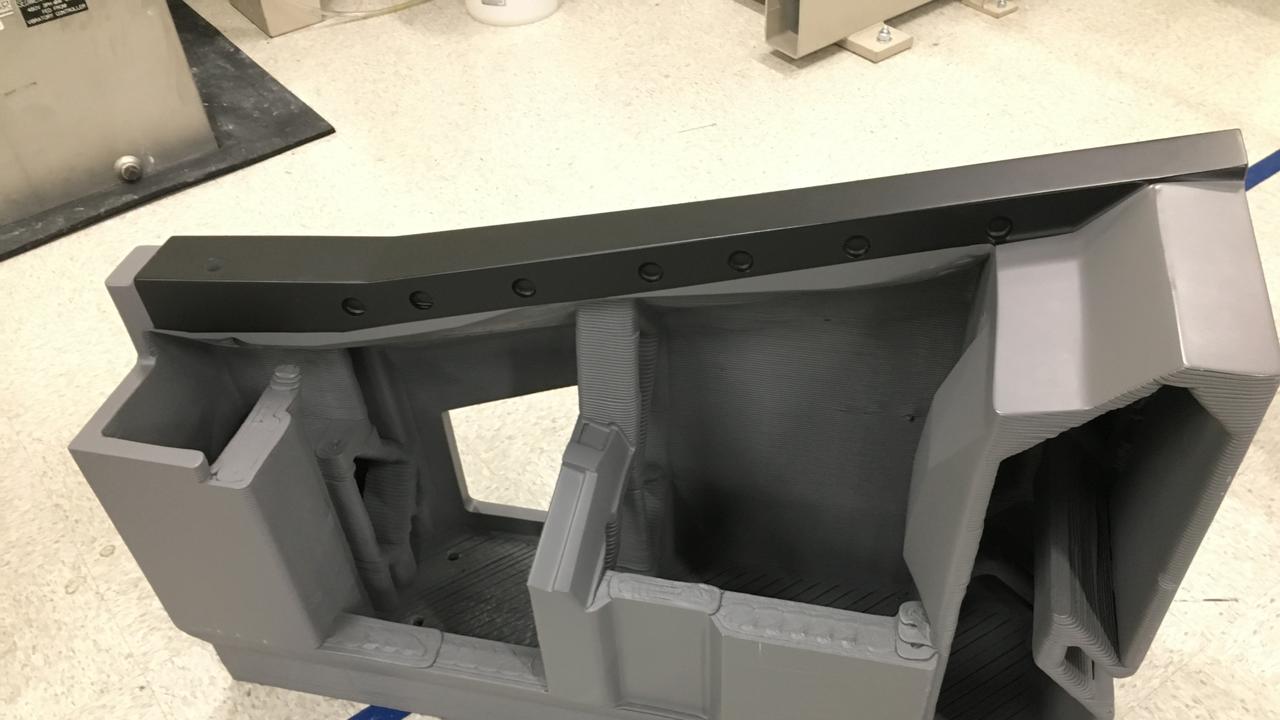

The manufacturer is fine tuning the 3D printing technology at its Orlando, Florida, innovation centre, with expectations it will start to take a chunk out of the cost of their F-35s high-fidelity, and high-priced training simulators, from the end of next year.

The simulators, which recreate the F-35 cockpit and then surround the pilot with screens that digitally reproduce landscapes from around the world, are designed to bring pilots to a high level of proficiency across a six-week immersion before they ever take off in the real thing.

“The trainer means you can get the same proficiency and the same sort of outcomes working in the trainer as flying in the jet — and you are able to do that without putting any burden on the jet,” said Lockheed Martin training and logistics solutions business development vice president Jeanine Matthews.

But, like the super stealthy and lethal jet itself, the simulators don’t come cheap. Lockheed Martin won’t reveal the exact price of their simulators, but Mike Rein, a communications director linked to rotary and mission systems part of the F35 program, said it was in the “ballpark” of $US10 million.

Australia will purchase six to support their 72 JSF aircraft. The final two are likely to be built in the timeline where 3D printing will take over up to half of the simulators cockpit manufacturing — replacing non-technology driven parts of the cockpit with ABS plastic embedded with kevlar and carbon fibre.

The cost-saving is part of a wider goal to reduce the price of the JSF program.

Lockheed Martin vice president and general manager of the F-35 program Greg Ulmer said the new Integrated Core Processor by Harris Corporation would take 75 per cent off the cost per unit and boost computing power by 25 per cent.

“We are aggressively pursuing cost reduction across the F-35 enterprise and, after conducting a thorough review and robust competition, we’re confident the next generation Integrated Core Processor will reduce costs and deliver transformational capabilities for the warfighter,” Mr Ulmer said.

The ICPs have also been designed to accommodate future upgrades.

An updated Distributed Aperture System (DAS) has already taken a $3 billion chunk out of the cost of the JSF program.

To date, Lockheed Martin production efficiencies have already wiped about $20 million from the cost of each aircraft.

The first F-35s produced cost about $125 million (USD) to build. As production has increased, the cost has fallen, with the latest crop down to $94.3 million.

Lockheed Martin is projecting that by 2020, the JSF will be down to $80 million each — with about 150 jets being built a year.

For comparison, a fourth generation Super Hornet costs about $70.5 million to purchase outright according to US Department of Defence figures released earlier this year.

With the sustainment of the F-35 expected to account for about two thirds of the program’s total cost, even small savings from things like 3D printing will substantially reduce costs in the long run.

And with Australia to be part of a global sustainment program where we will be responsible for repairs and maintenance to airframes, engines and components, as well as warehousing in the Asia Pacific region, there’s scope it could benefit the nation’s 3D printing industry.

Australian 3D Manufacturer’s Association acting chief executive Neil Sharwood said this was just one example of how Australia could benefit from embracing the technology here.

“Anything to do with defence industries is definitely a good way to go,” Mr Sharwood said.

“That’s where the government could look at giving support (to 3D printing).”

A broader sustainment program will mine big data for efficiencies and other means of saving money and time, as well as maximising the F-35s time available to fly missions.

It is expected that the Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS) that will be paired with every 14 jets Australia purchases will bear the brunt of this, communicating with JSF squadrons from around the world to learn how different weather conditions and flying conditions will impact wear and tear on different components.

A separate piece of hi-tech computing, the LM-STAR, will allow technicians to check avionics digitally — similar to the servicing process for many modern cars — and also minimising wear and tear through manual testing of parts and components.

“The whole ecosystem is the most sophisticated thing we have ever done in terms of supporting military aircraft,” Ms Matthews said.

The writer toured facilities in the United States as a guest of Lockheed Martin.