Lena Sjööblom posed for Playboy once in 1972 but her photo still appears

It’s almost 50 years since Swedish model Lena Sjööblom posed for Playboy but the revealing picture keeps turning up in an unlikely place.

There are four photos in this story, and your ability to see them can be traced back to one image of a Playboy model taken 47 years ago.

According to a new documentary, that simple fact is a symptom of a much larger issue.

Swedish model Lena Söderberg (nee Sjööblom) posed as the centrefold in the November 1972 issue of Playboy magazine, her first and last nude photo.

“I had never shot a nude photograph before Playboy … or after. [I was] a little bit nervous when we were going to shoot the centrefold but the photographer Dwight [Hooker] was so good, so he made me feel very comfortable,” Ms Söderberg said of the experience.

“People were very proud of me, I think, I know everybody thought the picture was really nice.”

But it wasn’t until a few months later that the photo would meet its eventual fate, going on to become arguably more studied than the Mona Lisa and leading to Lena being dubbed “the first lady of the internet”.

And it happened almost entirely by accident.

DIGITAL DISCOVERY

A group of men at the University of Southern California’s department of computer science were working on a way to turn physical photos into a digital language computers could understand.

The group were on the hunt for a new test image when someone walked in with Ms Söderberg’s issue of Playboy.

Their research would later lead to the creation of the JPEG file, the most commonly used file format for displaying images taken by a digital camera or posted on the internet.

Because of its historical significance, the photo of Ms Söderberg is now frequently studied in classrooms around the world, and is often still used as a test image for new compression algorithms and file formats.

But a new documentary argues the image should be consigned to history, and its continued use symbolises how women have been marginalised and left out of the technology industry.

Losing Lena, produced by production company FINCH in conjunction with the company’s science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) focused youth education initiative Creatable and social enterprise Code Like A Girl, is now streaming on Facebook Watch.

The 25-minute documentary takes viewers on a journey through the use of the Lenna image (which was gifted an extra N by its subject to ensure people wouldn’t mispronounce her name) and the impact it has had on women seeking careers in technology.

Central to the film’s argument is that the use of the image in classrooms, textbooks and computing journals reinforces the perception that STEM fields, already dominated by men, should remain so.

It’s not a new argument.

Noted mathematician and computer scientist Diane P. O’Leary previously argued the use of the image should be stopped for the same reason.

“Suggestive pictures used in lectures on image processing … convey the message that the lecturer caters to the males only. For example, it is amazing that the ‘Lenna’ pin-up image is still used as an example in courses and published as a test image in journals today,” Ms O’Leary said in 1999.

Two decades later and not much progress has been made in that department.

UCLA senior researcher in the democratisation of computer science Jane Margolis said the image was essentially “an in-joke”.

“When it goes up on the screen everyone laughs … well not everyone,” she said. “This is clearly a sign that this is not a space for both men and women.”

“It really made me feel uncomfortable in that moment, and made me feel like women were kind of made to be this joke in the context of this class where I was supposed to be learning as an equal,” Pomona College computer science student Maddie Zug told the filmmakers, recounting how the image was met with laughs in a high-school class of 30 boys, herself, and just one other girl.

The documentary also highlights the roles women played in the early days of computing in the 1940s, coding the software and programming computers for the US military and NASA.

In the 1970s, two male psychologists formulated a “personality test” to identify people who would become talented computer programmers as the industry was desperately searching for participants.

The two men determined good programmers “don’t like people”.

“If you’re looking for people who don’t like people, you’ll hire far more men than women,” Brotopia author and Bloomberg News anchor Emily Chang explained. “So women were pushed and profiled out of an industry that they were already succeeding in.”

Ms Chang also described how she asked a professor if they’d thought about how the use of the Lenna image may have been alienating to women.

“It wasn’t sexist at all,” he said, according to Ms Chang. “In fact, there were no women in the classroom at the time.”

Ms Chang said his statement (and its undetected irony) was indicative of what she called a “half century of passing the buck” on the lack of women working in computing and technology, and how the “stereotype of the anti-social, mostly white male nerd became ingrained”.

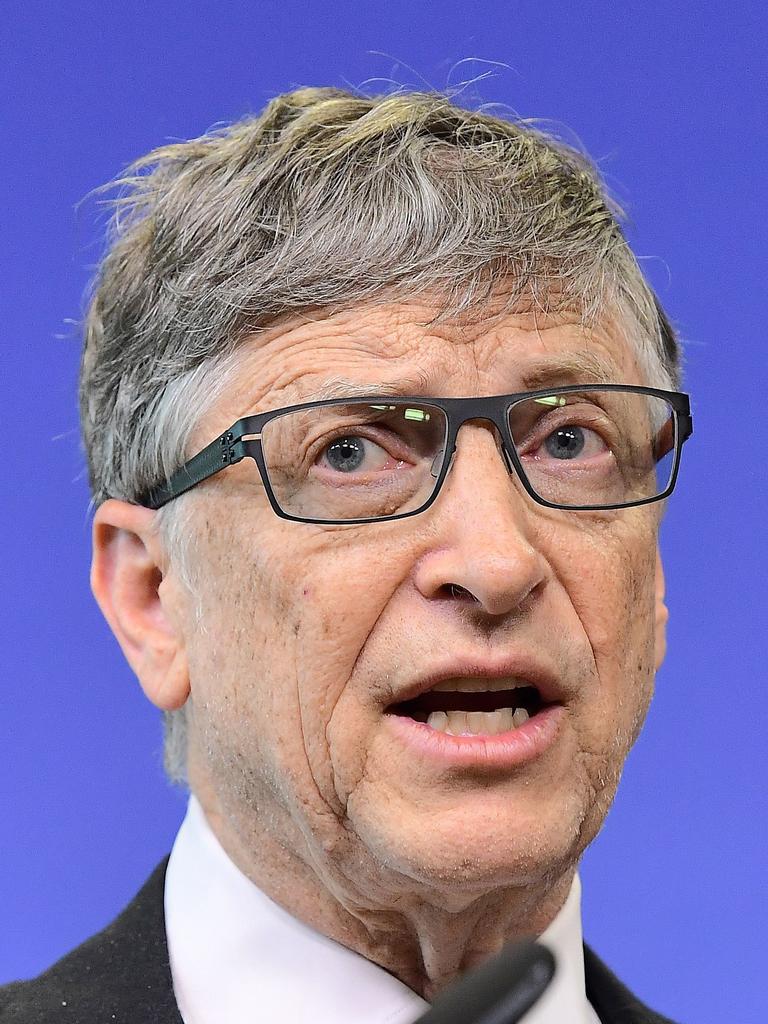

“Unfortunately that stereotype exists to this day,” she added. “When we think of people who can found a successful technology company we think of Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, and people who look like them,” Ms Chang said.

Throughout the documentary several women who formerly studied or currently study STEM degrees and work in the technology industry recall a similar feeling of being unwelcome by the men surrounding them, being forced to “laugh along” to fit in to the “tech-bro culture” and asked who they’re visiting when they show up at their workplace.

Code Like A Girl founder Ally Watson said the continued use of Ms Söderberg’s image in the tech sector symbolised its treatment of women.

“The role of Lena’s image in tech’s history is representative of so many of our industry’s shortcomings,” Ms Watson said. “Tech is used by everyone – no matter your age, gender, ethnicity, or sexual identity. But when our tech is developed by a small subset of homogenous individuals, it’s impossible for the end product to be without bias.”

SO WHAT IF NOTHING CHANGES?

The lack of diversity in STEM is becoming an increasingly concerning issue with the rise of artificial intelligence, where machines are being programmed to learn for themselves and act on behalf of all people, but inherit limited perspectives from the largely homogenous groups who design them.

Already the effects of a mostly male, white, and white-collar dominated technology industry have become apparent. Women have complained the ballooning size of smartphones designed by men have made them harder to hold in one hand.

Facial recognition software used by law enforcement around the world, including Australia, developed by white programmers struggles to consistently and correctly identify black faces. An algorithm used to determine credit limits on Apple’s Goldman Sachs-backed credit card mistakenly gave higher limits to men than to women, even when the women had a better credit score. Amazon’s machine learning recruitment technology taught itself to reject women’s applications because the company kept favouring men. A lack of diversity means that women (and not just women) are forced to use technology that wasn’t designed for them or with them in mind.

The government has a plan to help diversify STEM fields aimed at “increasing gender equity” by “enabling STEM potential through education, supporting women in STEM careers” and “making women in STEM visible”.

“In order to have the widest talent pool possible we need to ensure all Australians are supported to participate in STEM activities and careers,” Minister for Industry, Science and Technology Karen Andrews said when announcing the $3.4 million investment earlier this year.

“We know that STEM is the engine of technology, innovation and wealth – and gender-diverse teams are better problem solvers,” she added.

Work is also being done around the country to try and bridge the gender divide, by both schools and external organisations.

FINCH’s Creatable program was inspired by an attempt to hire a few “creative technologists” that led to universities around Sydney to send through 67 CVs of graduates, only two that were from women.

Last year the program took 140 young women from a number of Sydney schools and taught them how to “channel their creativity through technology”.

How do you think we can build diversity in the teams creating the technology that impacts on us all? Let us know your ideas in the comments below.