What will the Pentagon’s new $80 billion super stealth bomber look like?

CAN a 70-year-old Nazi super-weapon hold the key to what the Pentagon’s top secret, $80 billion future stealth bomber looks like?

LAST week, the Pentagon picked the plane that will be its bomber for the next 50 years. It will be built by Northrop Grumman. It will cost $US80 billion.

It must be able to fly unseen into heavily defended areas.

It must be able to fly high in order to spy on what’s below.

It must fly low to deliver weapons accurately.

It must fly fast to be able to make a meaningful difference.

It must fly slow in order to refuel from lumbering tankers.

But the B3 is being built to a strict budget after the disastrous cost-blowouts of the F-35 Stealth Fighter program. It’s also being designed from the outset to have a 50-year service life.

Northrop Grumman is under orders to have the first 21 examples of the new bomber rolling off the production lines in 2025. The Pentagon wants 100.

For this to happen, the design would have to already be in an advanced stage of development. Prototypes have probably already been built.

What will they look like?

We simply don’t know.

Every aspect of the new bomber is an intensely guarded secret.

But we can guess — based on a decade of intense lobbying by the US defence manufacturing sector.

Artist-generated concept images abound, providing tantalising glimpses of the direction of aeronautic thought.

But they are marketing exercises. They’re also probably intentionally misleading.

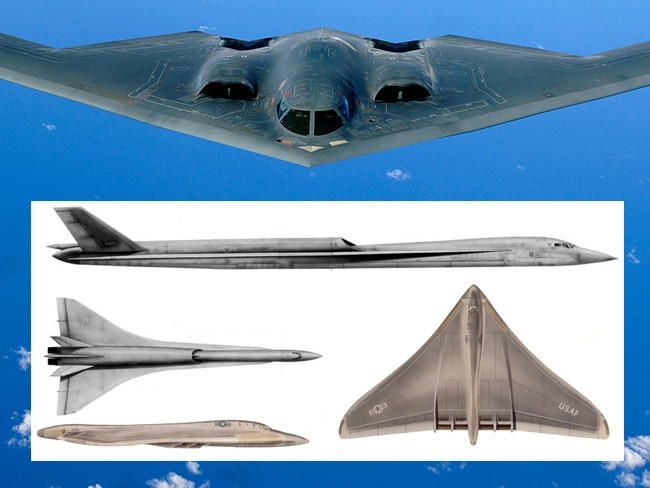

Before the B2 Spirit was revealed to the world, many were convinced it was a flying missile capable of incredible speed at incredible heights.

So what could a B3 end up looking like?

History could tell.

ON A WING AND A PRAYER

Northrop Grumman has significant experience in building stealthy bat-shaped aircraft.

Chances are the B3 will be a flying wing like its predecessor, the B-2 Spirit.

It is likely to be an evolution of existing technology — not a revolution — in order to keep costs down to about $US564 million each.

The military advantages of a flying wing design was realised by the Germans in World War II. One of their key secret weapon projects was the Ho-229 Horten, specifically intended to slip through allied radar nets to bomb distant but valuable targets.

It was sleek. It was fast. It was also partly built of timber laminate to reduce the strain on an economy under siege — as well as keep its radar profile down. Its intended performance was revolutionary for its time, carrying 1000kg of bombs over 1000km at 1000km/h.

Northrop Grumman analysed one during the design phase of the existing B2 Stealth Bomber. Another is currently undergoing restoration work by the Smithsonian Institution.

It’s the lack of protrusions which reduce a flying wing’s radar profile. But an even bigger advantage is its enormous lift-generating area: It can carry heavier loads over greater distances than conventional designs.

It was a concept — both in shape and role — which predated its successful entry into US military service by 40 years.

The reason for this time gap is simple: They’re incredibly hard to build. Every component has to be crafted to avoid unwanted radar reflections.

It’s not as though there hadn’t been other attempts to build flying wings. Northrop built the YB-49 jet-powered bomber prototype in 1947, but it was passed over as being too complex — despite its promising performance.

Flying wings are also very hard to fly. They have no tail.

The 30-year-old B2 only stays in the air because of its computer-activated control surfaces. These small flaps flutter hundreds of times every minute to correct the bomber’s attitude and produce the illusion of stability for the pilots.

The US air force last week took this level of automation one step further. The B3, they said, would be ‘pilot optional’. Meaning it will also be flown as a drone — or by an artificial intelligence.

UNSEEN ADVANTAGE

The B2 Spirit’s stealth comes from a mix of its low-profile shape and a variety of radar-absorbent materials. It both reflects radar away, and soaks radar into its skin.

The F-117 attack jet, famous for its role in breaking Iraq’s air defences in 1990, took a different approach. Its faceted surface panels did a better job at scattering radar waves. But it needed a tail to keep it controllable — undoing some of the good of its ungainly angles.

The B3 will probably need a blend of both, as each approach has its strengths and weaknesses. And the aircraft’s ability to remain unseen must last 50 years.

But it will be under the skin where the key differences lay. The B2 was an intensely expensive multitude of custom-made parts. With many of the companies that built those components long since shut down, keeping the complex aircraft in the air is proving to be increasingly difficult and costly.

This also means many of the B3’s capabilities will be hidden under the bonnet. Electronics can be swapped out, replaced and upgraded over its 50-year service life.

Modularity is a strictly enforced Pentagon requirement for the new program.

As target designating devices, computers and sensors become superseded — the ability to quickly pull that module out and replace it with a new one would be invaluable.

Particularly because electronics will be its core strength.

“It would carry on-board electronic attack equipment to supplement its stealth,” Loren Thompson, an expert at the Lexington Institute think tank, told AFP.

“It must be stealthy in all parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. It has to have electronic, on-board jamming equipment that would add to its stealth by preventing enemy sensors from working.”

Then there is a multitude of other developing technologies. The ability to ‘plug-and-play’ equipment such as defensive lasers, drone-controlling units and other unforeseen advances is vital to keep shrinking budgets under control.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Apart from the deliberately enticing, sheet-shrouded images produced by Northrop Grumman’s marketers, aviation experts have been speculating based upon what they know.

The lumbering 1950s-vintage B-52 relies totally upon escorting fighters to clear the air and strike-fighters to clear the ground of anything that can harm them on the way to their targets.

A fast-moving aircraft like the B1 is difficult to hide. It pumps out a lot of heat. But intercepting one with another aircraft or specialist missile is very difficult.

Aircraft like the B2 succeed only through stealth. They’re slow. They’re cumbersome. But being invisible gives them protection — for as long as that tenuous veil remains effective.

What is stealth now may not be in decades to come as Russia and China rapidly develop missile and sensor technologies to peel away the many layers of deception. Once gone, whatever the B3 has left behind must remain fundamentally capable.

To remain relevant for 50 years, some aviation watchers argue the B3 will have to be stealthy — but also fast and agile.

All we really know is that a Northrop Grumman design pitched to the Pentagon has won. And they’re being given $80 billion to build them.

Watch this space.