War against ISIS: Australian Major General Craig Orme explains our strategy

MAJOR General Craig Orme, who is leading Australia’s air strikes, has criticised the Islamic State as he revealed his plans for its “loser” leader and his terror group.

THE philosophy of war according to Major General Craig Orme, commander of the Joint Task Force in the Middle East overseeing Australia’s F/A-18F Super Hornet air strikes on the Islamic state, is do what you can and then get out.

This means no boots on the ground. But there will be “Merrells on the ground”, says Orme, referring to the hard-wearing lightweight runners preferred by Australian Special Forces, who under the leadership of 2nd Commando Regiment are preparing to make their way into Iraq for operational duty.

The Special Forces are tasked to “advise and assist”, which in real terms means they will stand side-by-side with Iraqi Security Forces in combat.

Despite this, Orme says Australia ought not think it is being drawn into the first phase of what will become another drawn-out Afghanistan War, where so much was spent in lives, money and effort for such questionable gains.

MAJOR GENERAL: ISIS ‘will get smacked’ by our defence forces

ISIS AND AL-QAEDA: The two will unite, expert says

“Can you redesign the world and bring peace in our time? That’s a bit of an ask,” says Orme from his soft-lit command headquarters in an air base in the United Arab Emirates. “But there are things you can do if you design your campaign and manage your objectives.”

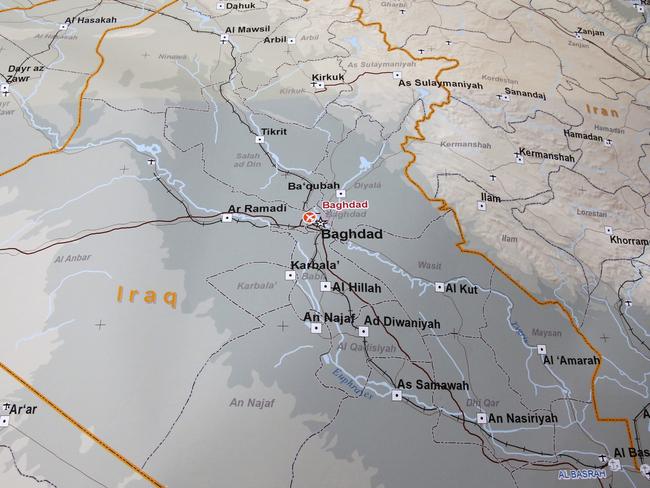

Orme, 53, is confident the Islamic state will be beaten in Iraq and blown back into Syria. He won’t give a timetable, because he says timetables are unforgiving on those who set them. But he told News Corp Australia that ISIL was “about get smacked”.

Orme says that ISIL has made serious tactical errors from the start. Part of it is that is has tried to act like a conventional army without the ability to resupply its frontline fighters, leaving them exposed to Coalition forces.

Most self-defeating, he says, is ISIL’s social media campaign. While frightening, it has mobilised a disgusted world against it.

“People confuse getting a message out with having a good message,” says Orme.

“They’ve used social media to terrify but their strategic message is not one of hope. It can’t be sustained. It’s not the message of a society that anyone could want to belong.

“Their message has been picked up by the world, but the message itself is bankrupt. It has no future, it has no promise. It offers nothing except death and destruction.

“Initially, people said, ‘Aren’t they clever with their social media’. Well, they’ve given us ample evidence for war trials. How could (ISIL leader) al-Baghdadi ever take his seat in the UN general assembly given his background?”

There is no political solution for ISIL if, as Orme predicts, they are crushed by a combination of air strikes and Kurdish and Iraqi armies, both which have taken heavy hits but are being reenergized with battlefield assistance by special forces from numerous nations.

While there is an argument that ISIL will never be defeated unless the United States puts big numbers of soldiers on the ground — along with the suggestion that Australia could be part of such an effort — this doesn’t sound right to Orme.

He agrees that ISIL can only be finished off by a combination of air strikes and ground forces, but says it must be the Iraqi and Kurds who push ISIL out of Iraq for the final reckoning, which will take place in their Syrian strongholds.

Orme was born in Wagga Wagga, NSW, grew up in Albury and moved to Sydney for his high school years. Hockey was his sport and as a country kid he played the Sydney teams. He later became captain on a Sydney under 16s hockey team, where he played the country teams.

“I learned from attending a number of schools (in the bush and the city) that everyone was scared of the other bloke, that you were intimidated by the people you didn’t know,” says Orme.

Understanding your opponent, he says, gives you a vastly better perspective of their weaknesses. For Orme, that means reading widely, a habit he picked up studying literature at Duntroon, where he completed an English honours degree.

His favourite author was Patrick White, who was “all about the extraordinary behind the ordinary”.

“I joined the army to get a degree,” he says. “The army was going to pay for it at a time when things were tight. That’s why I joined, but it’s not why I stayed.

“The military and literature are similar. It’s all about people. Warfare is an act of passion; it’s a human act. Whether it’s Shakespeare’s Hamlet or Richard III, it’s about the rise and fall of power, and of hubris.

“That’s what life is, that’s what war is about. If you understand that, you understand the essence of conflict.

“People are living and dying here. ISIL have a belief system and a worldview. We have a worldview. Invariably, whether it’s two people or nation states, it’s about the clash of ideas to the point where you can no longer reconcile them.”

Thinking soldiers must question their war and question themselves, he says. “Why is it OK to kill someone with an F/A-18 we haven’t met, yet it’s not OK to do it out the back of the pub on Saturday night? How do you understand those differences?”

Orme talks of a chat he had with a young F/A-18 pilot in the UAE, just before he embarked on the first strikes over Iraq early last week. “He said to me, ‘If I’m not comfortable about hitting a target (because of the potential presence of innocent civilians), then I’ll pull out.’

“That’s what I like about our Australians,” says Orme, who has spent a part of each of the last four decades with some involvement in the Middle East.

For most Australians, the conflicts between Shia and Sunni, wealthy oil states and broken fundamentalist nations, despots, sheiks, rampaging executioners, suicide bombers — and how the West fits into it all — is hard to take understand.

Orme says it’s simple: Iraq is the world’s fifth largest energy producer, supplying a huge amount of energy needs to north Asia. “Australia’s prosperity is directly linked to this,” he says. “If we can source it so it gets cheaply to Japan and China, that’s in our direct interests.”

Likewise, service people arriving on base in the UAE are given candid talks — the kind you won’t hear from Australian politicians — that the major reason we’re here is to support the US alliance.

“That is a fundamental pillar of Australian security,” says Orme. “Like any Australian who’s got a mate, we go and help. It’s not jingoistic, it’s not ‘all the way with LBJ’. The value of what the US offer us is profound in giving us the security we need.”

Orme says the Middle East and South Asia do have a desire for peace — even if it sometimes looks impossible given Yemen, Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Libya, the Sinai and Egypt. The problem, he says, is that each wants peace on its own terms.

The aim of the US-led Coalition, he says, is to contain the ISIL threat so it does not coalesce into one mighty regional war, with Sunni versus Shia.

For now, he believes Shia and Sunni are equal in their loathing for ISIL. “That’s why you’ve got a Gulf Coalition — Saudi, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and the UAE — who all went and bombed them the other night,” says Orme.

“Even if their weapons weren’t effective, on that single night when those Gulf states attacked ISIL, that was the message.

“The King of Saudi, whose responsibility is to protect the two most holy sites Islam, Mecca and Medina, and to protect Islam itself — that’s in his title — has said these people aren’t legitimate.”

To give it an Australian context, says Orme, it’s like going to a Collingwood supporter and asking them to sympathise with Carlton.

“Collingwood needs to understand the threat isn’t from Carlton,” says Orme. “It’s from soccer. Or rugby. It’s trying to get people to understand that it’s soccer taking over from Aussie Rules.”

Orme maintains that ISIL’s days are numbered. “They are not magic,” he says. “They are about to be defeated”. But this must be viewed with some caution.

In Afghanistan in 2010, one of his predecessors in the Middle East theatre, now-retired Major General John Cantwell, told me of Afghanistan fight: “We can and we will win this war.”

They didn’t. Instead, they are managing their exit with no clear result.

“What I’ve said is we can defeat ISIL militarily,” says Orme. “We are focusing on the strengths of ISIL and I do believe we can defeat that.”

Gone — at least in Orme’s mind — are the days of Coalition forces bombing from the air, surging on the ground, and then spending trying to rebuild the country and impose Western democracy.

He says the countries in his area of command have thousands of years of tribal governance that preceded democracy.

“If you try to impose other outcomes on a society that has its own complexities and orders, you end up failing,” he says. It is a mistake Western governments have continually made, and one that al-Baghdadi is now repeating with ISIL.

While ISIL appears to have forms of governance in place in its Syrian headquarters of Raqqa, or in Mosul in northern Iraq, it only relates to hard line edicts on behaviour, education and appearance.

It is one thing to execute someone in the town square, another to maintain the city’s power and water, to keep it supplied with food and to run public transport. Without them, you cannot win the people’s loyalty.

Orme says if he had al-Baghdadi sitting in his office, he wouldn’t question his beliefs, because he has no doubt the terror leader believes in what he is doing. But he would question his strategy.

“I would ask why he believes the tactics he’s chosen will achieve his ends,” says Orme. “Because I believe he’s a loser as a strategist and tactician, and I believe he’s leading his people to disaster.”