Anniversary of the phonograph: Thomas Edison invention that changed the world

This bizarre invention has almost definitely had a massive impact on your life – and you likely don’t even know what it is.

If you Google the history of the music industry, chances are you’ll stumble upon mentions of everything from Spotify and the iPod to Justin Bieber and Beethoven.

But there’s one man – and a very strange invention we would likely never have listened to music without – who we have to thank for it all.

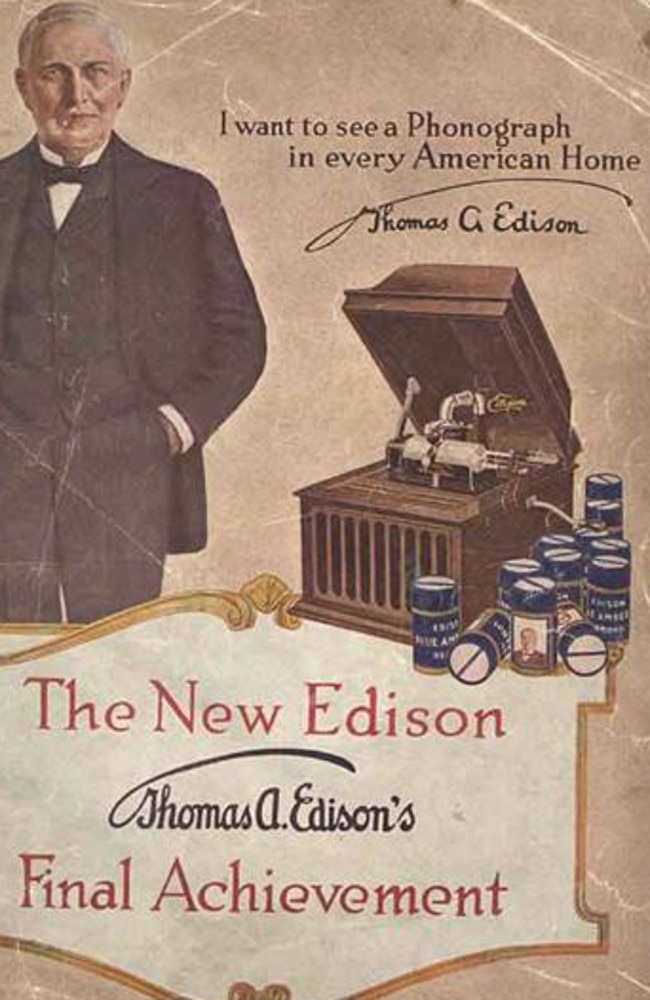

The story of sound recording, and reproduction, began 143 years ago on February 19, 1877, when Thomas Edison was issued a patent for the first phonograph.

Consisting of a sheet of tinfoil wrapped around a cylindrical drum which, when turned by a handle, both rotated and moved laterally, it hardly looked like a contraption worthy of changing the world.

And yet change the world it did. The utterly simple device was a marvel and amazed everyone, earning the prolific inventor his nickname: “The Wizard of Menlo Park”.

RELATED: The plane crash that saved your life

RELATED: Amazing story behind backyard staple

RELATED: Aussie inventions that changed the world

So how did the tinfoil phonograph come about?

It was developed as a result of Edison’s work on two other inventions: the telegraph and the telephone.

In July 1877, while developing the first telephone transmitter, Edison was working on a machine that could transcribe telegraphic messages through indentations on paper tape, to later be sent over the telegraph repeatedly.

This development led him to speculate that a telephone message could be recorded in a similar fashion.

After experimenting with a “telephone diaphragm having an embossing point and held against paraffin paper moving rapidly”, he found that the sound “vibrations are indented nicely” and concluded “there’s no doubt that I shall be able to store up and reproduce automatically at any future time the human voice perfectly”, according to the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences Thomas A. Edison Papers.

By the end of November, he had developed a basic design.

HOW IT WORKED

Instead of the paraffin paper used for his telephone diaphragm, Edison used a piece of tin foil wrapped around the drum as the recording surface.

As the drum moved, it passed under a touching metal stylus, attached to one side of a diaphragm. On the other side of the diaphragm was a small mouthpiece into which the operator spoke.

The sound waves focused onto the diaphragm caused it to vibrate, which in turn caused the stylus to vary the pressure on the tinfoil. As the drum rotated and moved across the stylus, a groove was embossed in the tinfoil consisting of indentations approximating the pressure patterns of the soundwaves.

Playback involved placing the stylus at the beginning of the groove made during recording, and winding the cylinder along once again.

The bumps in the tinfoil caused the stylus to move in and out and the diaphragm to vibrate – in turn moving the air in the mouthpiece and recreating the sound.

HOW IT WAS RECEIVED

Satisfied with his design, Edison enlisted machinist John Kruesi to construct the phonograph during the first week of December 1877.

Edison later recounted that when he first explained to Kruesi the machine was going to record and play back speech, “he thought it was absurd”.

When Kruesi finished constructing the phonograph, Edison put on the tin foil and recorded Mary Had a Little Lamb: fitting, because his daughter Marion was nearly five and his eldest son was almost two.

He then “adjusted the reproducer and the machine reproduced it perfectly. I was never so taken back in my life. Everybody was astonished. I was always afraid of things that worked the first time”.

The tinfoil phonograph was met with similar astonishment the following day, when Edison exhibited the new invention at the offices of Scientific American.

The staff were amazed, according to the editor, who later recalled, “the machine inquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a cordial goodnight.

“These remarks were not only perfectly audible to ourselves, but to a dozen or more persons gathered around, and they were produced by the aid of no other mechanism than the simple little contrivance explained and illustrated below”.

After witnessing a demonstration of the phonograph, Professor of Physics at the Stevens Institute Alfred Mayer wrote to Edison, telling him that his “marvellous invention” had “so occupied my brain that I can hardly collect my thoughts to carry on my work”.

“The results are far reaching (in science), its capabilities are immense. I cannot express my admiration of your genius better than by frankly saying that I would rather be the discoverer of your talking machine than to have made the best discovery of anyone who has worked in acoustics,” Professor Mayer said.

Reporters flocked to Edison’s laboratory in Menlo Park to see his invention for themselves and interview him – earning him his nickname, “The Wizard of Menlo Park” because of the miraculous nature of his inventions, which so radically changed how people lived.

While the scientific community saw the tinfoil phonograph’s potential as a scientific instrument, the general public – and Edison himself – imagined all sorts of uses for the new machine.

These included “clocks that should announce in articulate speech the time for going home”, “the teaching of elocution”, and, as if he were predicting the future, the “reproduction of music”.

Edison evidently had grand expectations for the invention, telling one reporter: “This is my baby and I expect it to grow up to be a big feller and support me in my old age”.

The phonograph eventually became the vinyl record, which became the tape, which evolved into the CD. From the CD, there was online music service Napster, and then in 2001 came Steve Jobs and the iPod.

In 2020, where there are kids who’ve likely never even owned a CD, it’s hard to believe that the catalyst for our ability to listen to music was a humble piece of foil.