This is where the US government will hide during a nuclear war

HIDDEN across the US are secret Doomsday bunkers, which are to be used by government and military officials in case of a nuclear war.

MAYBE Doomsday preppers aren’t so crazy after all.

As nuclear threats loom from countries like Iran and North Korea, the US is knocking the dust off decades-old bunkers intended to protect government officials — and even start a new civilisation — in the case of just such a nightmare event.

Journalist Garrett Graff takes readers through the 60-year history of the government’s secret Doomsday plans to survive nuclear war in his painstakingly researched book “Raven Rock: The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself — While the Rest of Us Die” (Simon & Schuster), out now.

He focuses on the Cold War-era government bunkers across the country that were built to house the President and various Washington elites — members of a so-called “shadow government” in the worst nuclear Armageddon scenario.

Since September 11, 2001, Congress has intensified their interest in and funding of top secret “Continuity of Government” (COG) in ways not seen since the Cold War. With hundreds of newly declassified documents, the book, currently in development with NBC as a TV show, includes never-before-heard intel on the country’s top secret bunkers — mythical places like Raven Rock and Mount Weather.

Here’s the low down on some of these bunkers down below …

RAVEN ROCK — LILLINGTON, NC • FOR MILITARY

Built near Camp David to house the military, as a backup for the Pentagon — and perhaps even the President — during an emergency, Raven Rock has retained an air of secrecy ever since construction started in 1948.

Not that it could remain completely clandestine, given the 300-person team (including miners poached from the Lincoln Tunnel dig) who carved a 3,100-foot tunnel out of granite in Raven Rock Mountain near Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania.

“There were very few engineers with the expertise to hollow out a mountain and build, in essence, a freestanding city inside of it. The US government turned to the construction firm Parsons Brinckerhoff, which had developed unique tunnelling expertise working on the New York City subway,” Graff told The Post.

Locals caught on and word spread to the media, who dubbed the project “Harry’s Hole,” after President Truman who greenlit the project.

Opened in 1953 and designed “to be the centrepiece of a large military emergency hub,” Raven Rock provided 100,000 feet of office space (not counting, Graff writes, “the corridors, bathrooms, dining facility, infirmary or communications and utilities areas”) that could hold about 1,400 people comfortably. Two sets of 34-ton blast doors and curved 1,000-foot-long tunnels reduce the impact of a bomb blast. The compound has undergone several rounds of upgrades — new buildings were added as well as updated technology and air filtration systems.

By the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, many government officials recommended closing Raven Rock for good. “You’d feel like you’re walking into a dinosaur,” one said. In 1991, President George H.W. Bush ceased 24 hour operations, effectively forcing the site into standby mode.

Then September 11 happened. By the second anniversary of the attacks, the government had injected $652 million in upgrades. The annual budget ballooned and construction started on new buildings.

The underground city “added 27 new fuel tanks in 2012, each of which could hold 20,000 gallons,” Graff writes. Raven Rock is believed to have 900,000 square feet of office space now. Today it holds between 3,000 and 5,000 government employees — no families.

“Families would have been prohibited from Raven Rock — as they would have been from effectively all of the Doomsday bunkers,” writes Graff, “although in recent years as the veil of complete secrecy has lifted, family members of Raven Rock personnel are allowed to visit it for specific ceremonies. So at the very least, family members today can picture where their relatives will spend Doomsday, even as they’re barred outside.”

PETERS MOUNTAIN — APPALACHIAN MOUNTAINS, VIRGINIA • FOR INTELLIGENCE AGENCIES

“Peters Mountain, Virginia, is a longstanding facility, run undercover as an AT & T communications station — there’s even an AT & T logo painted on its helipad — but its real purpose is as one of a half-dozen secret facilities known as AT & T “Project Offices” that are actually key hubs for government continuity planning. It’s a department-store-sized bunker, capable of housing several hundred people, and has undergone a $67 million renovation in recent years that would help it serve as one of the relocation sites for intelligence agencies in the event of an attack on Washington,” says Graff.

MOUNT WEATHER — BLUEMONT, VA. • FOR CIVILIAN GOVERNMENT

The President could end up at any of the Doomsday facilities, but in general terms Mount Weather is designed to hold the civilian leadership of the US government, including the President, the Supreme Court, Cabinet officials, and some senior congressional leaders.

A year after Raven Rock opened its doors, work began on Mount Weather, once an observatory for the Weather Bureau (hence its name) and, for a brief time, Calvin Coolidge’s summer White House home. Tunnels excavated through thousands of tons of greenstone lead to a true underground city that can house thousands of staff. Under JFK’s tenure, the bunker expanded to sewage treatment plans, reservoirs for drinking water and even its own fire and police departments — all underground.

Mount Weather boasted “extensive computer systems” — including the forerunner to now ubiquitous chat programs like AOL Instant Messenger and Skype, to respond to possible communication crises. Mount Weather also housed a “Survivor’s List” of 6,500 names and addresses of people — government employees and private citizens — viewed as “vital” and key to maintaining “essential and non-interrupted services” in an emergency.

Unlike Raven Rock, Mount Weather has an extensive above ground facility that FEMA uses for routine staff training and seminars. “There’s even a bar, the Balloon Shed Lounge, the name a nod back to the site’s origins as a weather balloon launch station,” Graff tells The Post. In 2016, it embarked on “a significant infrastructure upgrade” so the facility is “capable of supporting 21st century technology and current Federal departments and agencies’ requirements,” Graff adds.

Mount Weather has been updated after 9/11 because “there’s now a greater focus in government planning on ‘devolution,’ that is, ensuring that backup facilities are always staffed and ready to assume control if the worst happens — rogue states or terror groups today offer more of a threat that a surprise attack on Washington could destroy the capital without warning,” Graff says.

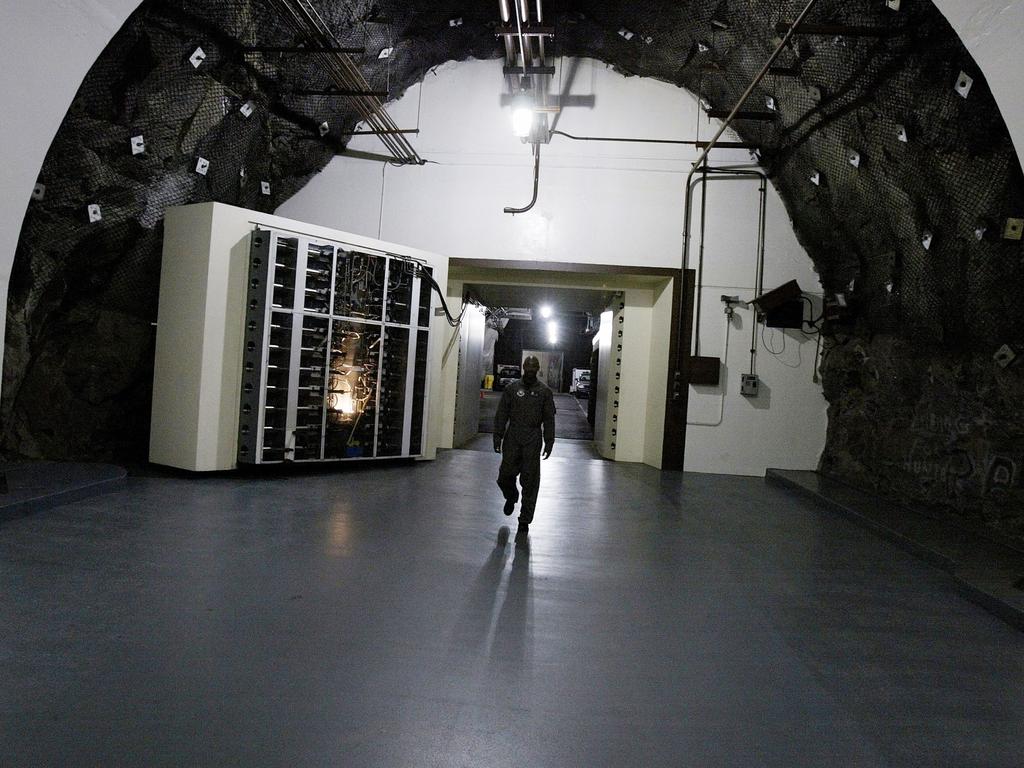

NORAD — COLORADO SPRINGS, COLO. • FOR AIR DEFENCE

Unlike Raven Rock and Mount Weather, the military’s North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was never kept secret from the public. “NORAD is specific to North American defence — it includes the command post responsible for defending both Canada and the US from air attacks, whether that’s terrorists, Russian bombers, or North Korean missiles,” Graff says.

The difficult, three-year project — started in the 1950s as a reaction to creeping Cold War paranoia — was built when we were first understanding the damage that could be inflicted by electromagnetic pulses (EMP) that would follow a high-altitude nuclear explosion. It became one of the first facilities protected against EMP. Today most new facilities are protected against it (including Doomsday planes built for the president), but “it’s an intensive and expensive process, so it’s useful to rely on older sites” like NORAD.

Five chambers inside Cheyenne mountain hold reservoirs for water and fuel. There is even an underground lake, which requires rowboats to patrol. In the beginning, nearly $40 million went into equipping it with the best computers and electronics, including three room-sized Philco 212 computers and 15 console displays (cutting edge technology at the time). During an emergency, NORAD could house 1,000 people for a month.

The Pentagon nearly closed the book on the facility, which costs about $250 million a year to operate, but reversed course after 9/11 — installing about $700 million in communications and computer upgrades five years after the attacks. One $15 million project in 2004 nearly doubled the main command center’s 540 square feet to accommodate more staff.

After a brief return to standby mode in 2006, the Obama administration brought NORAD back to life. It began running full-scale continuity drills and even sealed the blast door entrance for 24 hours — the first time a test of that magnitude had happened there. In 2015, the Pentagon announced that it was restaffing the bunker as “the rising threat of electromagnetic pulse attacks against the United States, perhaps even by a new nuclear-armed nation like Iran, meant that the NORAD bunker ... was a perfect bastion from which to defend the nation,” Graff writes.

WHITE HOUSE FRONT LAWN — WASHINGTON, D.C. • FOR THE PRESIDENT AND KEY OFFICIALS

The most mysterious of all bunkers is this one, located right in the heart of our nation’s capital.

“There’s definitely a bunker under the White House, known as the Presidential Emergency Operations Center (PEOC), which is where Dick Cheney was rushed on September 11th and where he spent the day helping to lead the government’s response. It’s a small facility, not designed for long-term use, just to hold a few dozen people for a few hours, which traces its roots all the way back to FDR, when the first bunker was built to protect against a surprise Nazi attack. Later, Truman expanded it and the facility has been updated again in recent years since 9/11 when the attacks showed how limited the communications systems were. For instance, Vice President Cheney couldn’t listen to both CNN and to the government’s videoconference at the same time on 9/11,” says Graff.

Far less is known about the bunker update done during Obama’s first term. The massive expansion was built beneath the North Lawn of the White House and was intensely guarded from the prying eyes of the press. The $376 million project seemed “far too extensive to be merely an airconditioning upgrade,” writes Graff.