Netflix’s Lisa Nishimura, the woman behind Tiger King and Making a Murderer, on how she finds hit movies and TV shows

A key Netflix executive says people assume that its trove of data drives all of their creative decisions. She says that’s a “misperception”.

Lisa Nishimura is responsible for some of your most obsessive binges. Making a Murderer, Wild, Wild Country and Tiger King – that’s all her.

A Netflix veteran of 13 years, Nishimura first joined the company when it was still a DVD rental-by-mail business, when US customers would receive and return discs through the post in distinct red envelopes.

Originally tapped to oversee acquisition of independent titles for Netflix, it was as the head of documentary and comedy where she’s had an outsized impact.

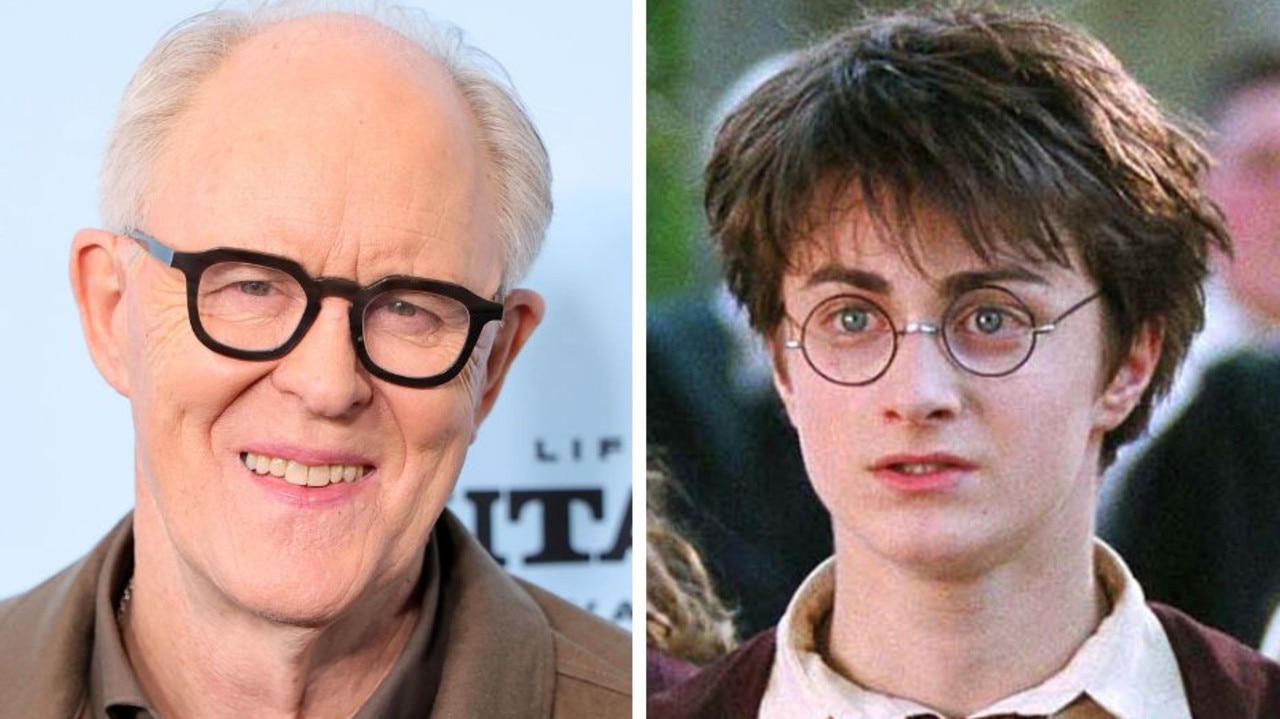

No one else could’ve foreseen the mania which followed the debut of Making a Murderer, a docuseries about a man in Wisconsin who few people had heard of but whose story filled 10 hours of gripping television.

Praised by filmmakers such as Ava Duvernay, who worked with Nishimura on her Oscar-nominated documentary feature 13th, the executive’s track record speaks for itself.

Netflix has won an doco Oscar every year since 2016 while Tiger King, according to Netflix metrics, was watched by 64 million households in the month after its debut.

Which is perhaps why it wasn’t surprising that she was promoted to vice-president of independent and documentary features a year ago, where she is now responsible for commissioning stories from passionate filmmakers.

In a wide-ranging chat, Nishimura takes news.com.au through what her job involves, including the “misperception” people have about how Netflix uses data, that first 24 hours after one of her commissions debuts and that “tingling” feeling she gets when she believes she has a winner in the room.

It’s been just over a year since you took on the indie movies portfolio as well as docos, giving you the opportunity to flex some muscles you haven’t used in a while, what’s that been like?

My original role at Netflix was to oversee and manage what I would call non-major studio film and TV – and that included categories such as Japanese anime, Bollywood, foreign film and more. It was an incredible opportunity and an education for me because it tested the theory that if you actually made great stories available to people, what would happen?

We got to see that when you made it easy for people to connect to that story, they were really quite passionate, curious and open to engaging with brand new stories.

RELATED: The Old Guard director on what makes a great action movie

In returning to scripted to feature, it feels like it’s a space that I have never left. I’ve always loved storytelling in all the different forms.

Sometimes, when an idea is fairly nascent, it’s great to be able to have a conversation and shape what form that story might be. So if it’s not at pitch stage, when somebody comes in and they think ‘OK, I think this is a series’ and then by the end of the conversation, they recognise there’s a perfect three-act structure and it should potentially be a film.

So I feel really fortunate that I sit at this cross-section where it allows the story to dictate the frame.

Have you managed to turn a few filmmakers around into considering a scripted feature instead of a docuseries which may have been what they were pitching?

It’s not about turning them around, I don’t ever go into it with an end in mind. It’s oftentimes in the multiple iterations of talking through a project that you recognise and realise that it needs to be something different.

When I met Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi, who are the creators of Making a Murderer, at the time there hadn’t been a documentary series for a while. The Staircase was many decades before.

Moira and Laura, at that time, were eight years into the project, if not more. They recognised the vastness of the material that they had and they couldn’t conceive of it being just a feature. So to be able to then talk it through and say, “Well, you know what, let’s not do it as a feature, let’s try it as a multi-episodic” was great.

They had pitched it around and were being told it had to be a film.

RELATED: Highlights of the virtual Melbourne International Film Festival

Another example is working with Orlando von Einsiedel, who made a short documentary about the conflict in Syria, The White Helmets. His biggest concern was that it was six years into the conflict and people were forgetting, it was just becoming noise and these children and families were being left without any support.

So we talked to him and asked, “what are the biggest priorities, what are you looking to accomplish?”. And timeliness was important. So we were able to talk through that and recognise that. We could make a short faster than a feature, so it ended up being a 40-minute short and it went on to win the Oscar.

We were able to say, “OK, let’s pivot”.

It sounds like maybe the instincts for unearthing those stories are similar in documentary as they are in narrative features?

I think storytellers are remarkably curious individuals. The best stories, whether they are fiction or non-fiction, are the ones that have that universal ability to resonate with elements of ourselves, when we see ourselves reflected back.

In gifted hands, there’s a humanity in the way that even the most flawed characters, and who among us isn’t flawed, can have these journeys. When we see that, it allows us to be not just wildly entertained but also to have compassion and empathy in a way that I think can be incredibly engaging.

You must hear so many pitches every week – what gives you that “tingling” feeling?

When you take a pitch, whether it’s in fiction or non-fiction, when you see a creator that comes in with a clarity of vision, they’re incredible thoughtful and they’ve considered the emotional arc, and they sit there and you have this sense that they are the only human being on the planet that can tell that story, it is very electric, “tingling”, as how you described it.

The flip opposite is when you sit with a creator and they say, “Well, what do you want it to be?”.

I appreciate the collaboration so if the question is asked in the spirit of “Here are my thoughts, I’m curious what yours are” then that’s wonderful. But I have had a few pitches where someone comes in and it’s like, “well, what do you need it to be”, and that worries me instantly because I want you to have a point of view.

Netflix is famously a company that has a lot of data on its users. What happens when you believe in the creative idea of someone’s project but maybe the data is telling you something different, that maybe it’s a subject that audiences aren’t tuned into?

We are fortunate that we have a lot of data but it’s more about having informed intuition, right? The data is directional to some degree, but I’m here and my very talented team is here. My team are creators because they are listening to the story and they are tapped into the zeitgeist.

Most importantly, we are listening to the storytellers and their vision and ambition, and how they plan to bring that to life.

The thing about data is that it’s wonderful for telling you what happened historically but if it hasn’t happened yet, it’s not an input. So you really have to bring an open mind and an open ear to what the vision is and to have the shared courage to lean into something exciting and new.

There was nothing in the data that would have told me that Making a Murderer would become Making a Murderer.

There’s a point in which you say, “I believe in this creator, I believe in this voice, I believe in this storytelling universe”. But we do our homework – we work very closely with our filmmakers and we share information with them as much as possible to the things that we think might be challenging or an opportunity.

Data is an integer in the decision making. Sometimes people have the misperception that the data drives everything, and that’s not the case. It’s a wonderful tool but it’s one arrow in a vast quiver of things that we’re looking at.

To the point where the data is directional, is it useful when you see something like To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before really pop in a way that people maybe didn’t expect it would to that degree, would you use that data to then go out and commission more projects in the same genre or have the same actors?

What it does is help us to understand that moment in time.

With something like To All The Boys, which was a wonderful surprise, if you watch the film, just qualitatively you knew there was something really special and appealing about it on a lot of different levels. There was a wonderful positivity to the film and an inclusive energy in the casting.

We were delighted with the audience that showed and continues to show up for To All The Boys, and that helps us understand the size, scope and potential of that storytelling audience. It gives us the confidence to further lean in into that space.

But we didn’t have all of that when we said yes to To All The Boys. We just knew that the filmmaking team, Jenny Han’s books and the idea of putting a new face to a heroine was something we were deeply committed to and excited about.

Tell me about your experience of the first 24 hours after one of your commissions goes live on the service. Do you wait for the data to pour in at 12.05am or are you asleep?

I would be asleep! It depends on the project, depends on the filmmaker. Some filmmakers are texting me all the time.

I think something storytellers are seeking is a connection to the audience, that sense of relevance that you are touching people. Now that shows up in social media. If something is connecting with audiences, you hear people wanting to share their experiences of it.

Film and TV are such communal experiences and if somebody feels moved by something, it’s a real act of love to say, “This touched me so much”. That conversation is happening in the social media world. That’s why we make it available to everyone at once.

So in that first 24 hours, I’m often looking at social media, going back and forth with a filmmaker excitedly, being surprised with the thing in the movie people liked.

Some films take years to make, some documentaries take decades, and then that moment when it’s released to the world, it’s not yours anymore. It belongs to the world now and every person that sees it watches it with a completely different set of experiences that forms the lens through which they watch your work.

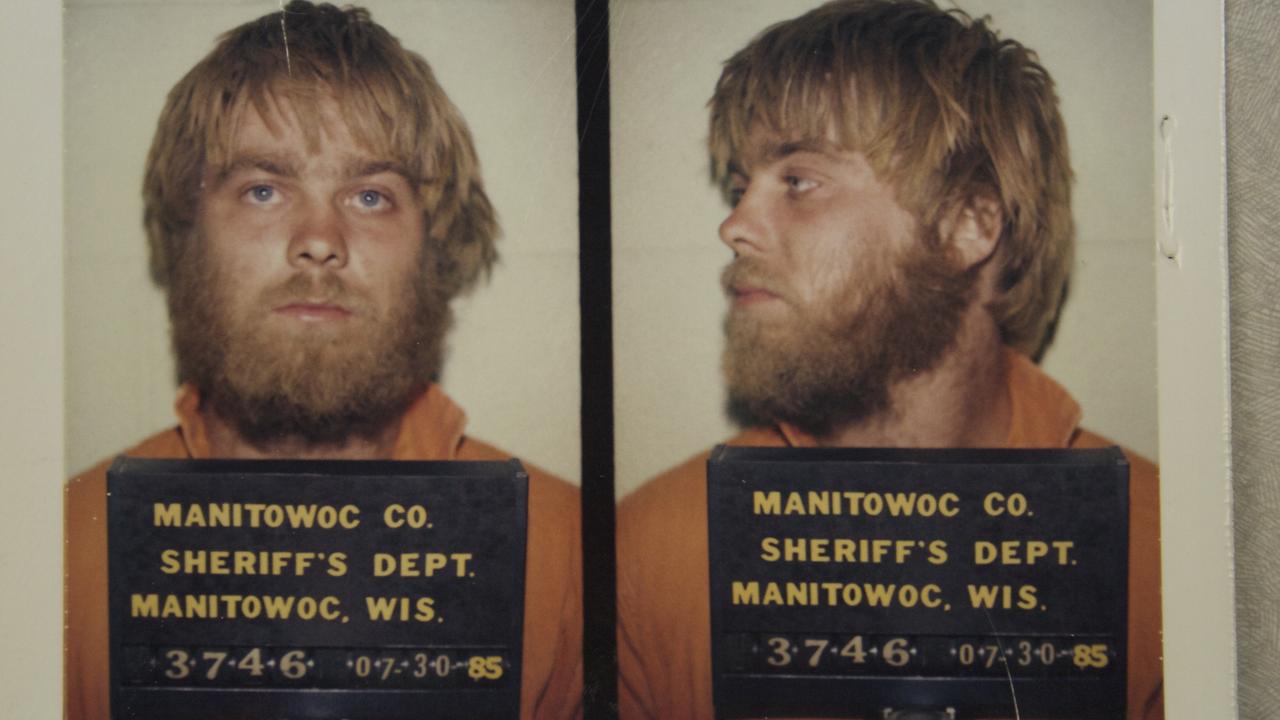

Tiger King just blew up – at what point do you know that is going to be huge? Is it in the lead-up or is it after it’s been released?

I don’t believe anybody that tells you they knew that Tiger King was going to become Tiger King. There were so many factors that went into that’s success.

When I took the original meeting with the filmmakers and we started talking about the subjects and the materials they had, it struck me that they had an enormous amount of access and that a lot of it was verite. So, it’s not meant to be someone telling you how to feel.

You learn a lot about a person just following them around, it’s not actually in what they’re saying, it’s in watching them in their space. That kind of filmmaking takes a lot of time and a very big commitment.

Tiger King is a great example of watching that social media response in the first week. You started to see people leaning in to different aspects of it, debating each other, having entire conversations about it.

And certainly the fact that the series was released at a time when people found themselves at home, with probably more time on their hands, which, of course, were very unfortunate circumstances, but it is a series that benefits from being watched in a concentrated period of time.

What have you commissioned or acquired in your first year back in the indie portfolio that you’re really excited about?

We are very committed to the discovery of new voices, so we’re thrilled to be working with Radha Blank who has a film called The 40-Year-Old Version for which she won the US Dramatic Competition Directing award at Sundance.

It’s an autobiographical story of a woman who wants to be an artist, a woman rounding the corner to 40, an African American voice who wants to be sincere in her creative expression.

This is something that feels very electric and it’s a deeply, deeply personal scripted feature.

We have a wonderful film coming called The Sleepover, which is for kids and their parents. I does something that’s really tricky, which is to make a film for children to love and find engaging, that parents will also enjoy.

Then being able to work with someone like Charlie Kauffman, working on his new film I’m Thinking of Ending Things, which is with Jesse Plemmons, Jessie Buckley and Toni Collette, that was incredible.

It’s just what you want in a Charlie Kauffman film, because it was challenging and requires to really, really think deeply. Such a ride.

[Edited for length and clarity.]

Share your movies and TV obsessions | @wenleima