The toxic towns in China recycling Australia’s unwanted waste

WE PUT out the recycling bin without a thought but it ends up here. A remote town with waste as high as houses.

AT FIRST glance it’s a touching moment. A newborn nursed by its mum in the garden of her home.

But there are no trees in this backyard, no well-kept lawn. Instead, the mum squats surrounded by mountains of filthy plastic rubbish. Soiled food packages, plastic crates and even blood bags encroach on the mum and her new baby.

Soon she will head back to work sifting through the debris for hours on end. She will then stand close by as it is melted down into pellets, the fumes wrapping themselves around the young family like a toxic blanket.

Located close to the north eastern Chinese city of Qingdao, this is one of the legions of remote toxic towns that process the world’s plastic recycling.

By the container load, the cast-off plastic comes from Korea, Europe and the US.

Almost certainly, a proportion will have come from the homes, or more specifically the recycling bins, of Australia.

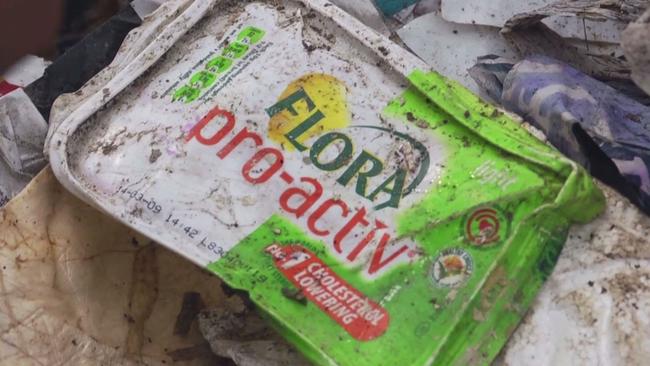

Among the plastic are familiar brands; empty packets of Hill’s Science Plan dog food and Flora margarine tubs.

“It’s dirty, tiring and I don’t make much money,” said Kun, who runs the small firm processing rubbish.

Kun’s business, is the subject of the documentary Plastic China, showing this Sunday in Sydney as part of the city’s annual Antenna Documentary Film Festival.

The only employees are him, his wife and mother and the family next door — including the new mum. The children of both families are also part of the workforce.

Almost every inch of the two homes and shared backyard has been invaded by plastic, just a small space made for a dinner table and bed.

“[I do it] because I have no choice. It’s for my kids, my parents,” says Kun. “I’m just a farmer. I don’t have any other skills just dirty work like this.”

David Rokach, festival director of Antenna, said Plastic China was an “incredibly important” work.

“The film looks at the direct impact that the waste industry has on families and reminds us that while we may not see it, our own actions can have an effect on people living thousands of kilometres away,” he said.

Directed by Jiu-Liang Wang, the film focuses on the children. Yi-Jie, 11, feisty and smart, dreams of going to school. She picks through the plastic, finding objects to make into collages. But her father, who spends his days sifting and nights drinking, says he can’t afford the fees.

Mostly, it seems the children know no better. One emerges from a mound of plastic. “We’ll make a space here to sleep,” he says as he rolls in the shred, like a litter of white translucent leaves.

They loiter by a river, scooping up dead fish from the scum of plastic off cuts, for that night’s dinner.

They have dreams too. Of heading back to their home province of Sichuan where life was greener and not constantly dominated by plastic piles, as big as a house.

However, profits are slim. Kun’s neighbour gets just US$5 a day for his labour. A bus ticket to Sichuan costs US$85.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, during 2011-12, Australia exported 4.4 million tonnes of waste valued at more than $2 billion. That accounted for 0.8 per cent of total exports.

China, including Hong Kong, was Australia’s main trading partner for plastic waste receiving around 155,000 tonnes of plastic to be recycled.

The country is the world’s largest importer of plastic waste. Nearly 30 towns are engaged in processing the refuse in highly toxic environments.

But China is closing its borders to the international trade. A hazardous waste expert has told news.com.au that Australia’s kerbside recycling system “could collapse” without a market to ship the waste to.

Already, the market is shrinking for recycled glass. Hundreds of thousands of tonnes of recyclable glass lies in Australian warehouses waiting for someone to buy them.

The process of turning rubbish into a saleable commodity is difficult, messy, hot and never ending.

Sweat trickles in rivers from Kun’s head as he funnels piles of plastic — they have already been sifted and ridded of contaminants by his family — into a shredder.

The shredded piles are shovelled into huge troughs, to remove muck and grime. With not a care, Yi-Jie washes her hands and face in the vast vats of rapidly greying liquid.

The flakes are then melted down in furnaces, releasing their toxins along the way, into a pallid molten sludge before being compressed into pellets that can be resold.

Dr Trevor Thornton, an expert in hazardous materials management, at Deakin University, said plastics recycling was heavily regulated in Australia precisely due to its potential environmental impact.

“When you heat plastics, a variety of substances can be released, but its impact is relatively benign to the environmental and human health if it is [processed] according to the requirements,” he said.

“However, if not done this way it can be very nasty. We don’t have control over the [safety] controls in other countries and if it’s not done well, this can pose a significant risk to workers, the wider community and the environment.

“It’s hard and hazardous work”.

In July, China made an announcement that shocked the waste world. From 2018, it would no longer import other nation’s rubbish.

The aim is to fight the country’s choking pollution and modernise its industrial abuse.

That could have big ramifications for small scale plastic processors like Kun.

It could also increase demand for what is known as “prime virgin” plastic products, plastics that have not been recycled.

Already, Chinese authorities have forcibly shut down a number of small recycling factories in the southern Guangdong province.

“If we cannot send recyclables to China there is a real danger our kerbside recycling system may collapse,” said Dr Thornton.

“Going to other countries could possibly be more costly, they may not pay as much and then the question is will recycling still be able to be viable in Australia?”

He said the Australian government should provide incentives for organisations to use recyclable materials.

As winter draws in around Qingdao, the cold winds blows across the fields and into the two families’ homes.

To keep warm they stitch together identical food wrappers to make a kind of makeshift insulation. One wall is completely covered in an almost pop art work made-up of identical Kit Kat wrappers.

Kun’s dream is to make enough money to get a new car. And so continue to consume, just as the Western families are whose rubbish his family endlessly sifts through.

Plastic China will show at Sydney’s Chauvel cinema on Sunday 15 October as part of the Antenna Documentary Film Festival.