New data shows Western Australia most at risk from being struck by tsunami

YOU might not think Australia could be hit by a tsunami, but new research has pinpointed which cities are most at risk of a disaster.

WHEN we hear the word tsunami, for many of us it might conjure up harrowing scenes of flattened communities picking up the pieces in often faraway countries.

However, new research from Geoscience Australia shows, the threat of a massive waves causing destruction is one Australia should be taking very seriously.

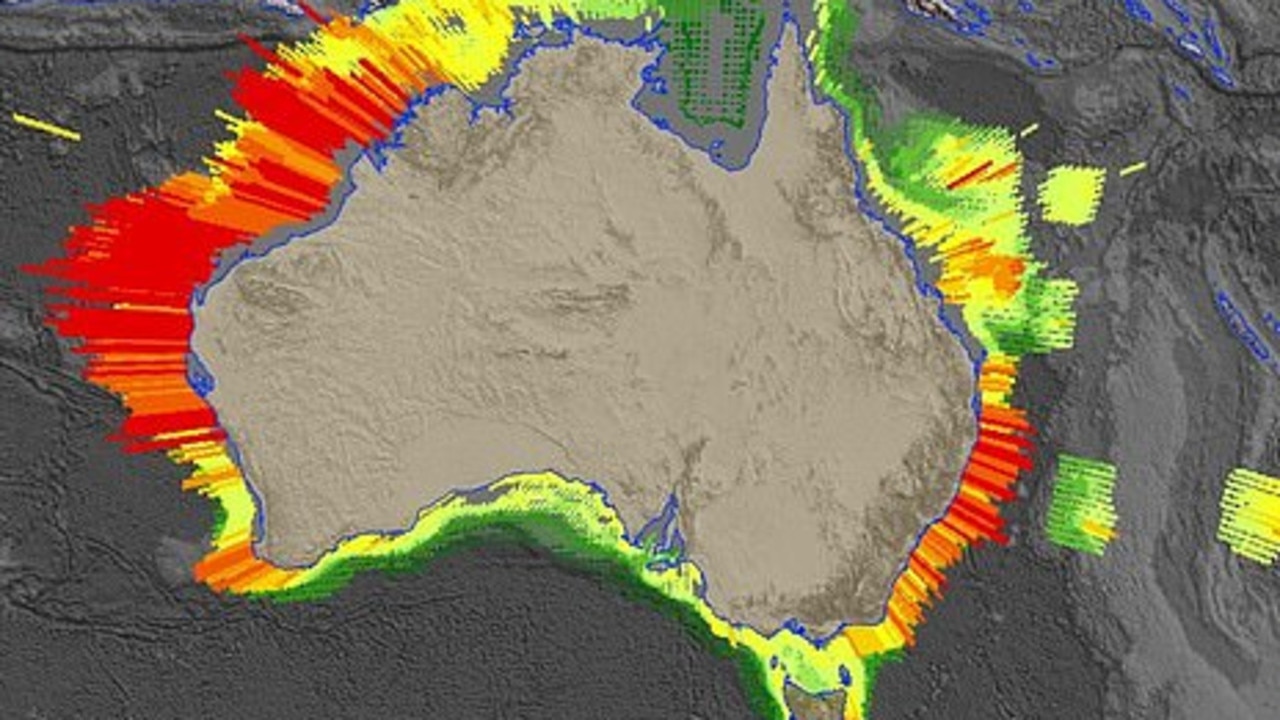

Its Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Assessment (PTHA) released this week shows which parts of the country are most likely to be hit and includes data for more than 500,000 possible earthquake and tsunami scenarios in Australia.

The northwest coast of Western Australia is particularly at risk, according to the research, because of proximity to Indonesia’s active and turbulent earthquake zone — making it far more likely to be struck than the rest of the country.

And, it also shows our heavily populated east coast is also at risk of being hit.

Hazard modeller Dr Gareth Davies said although most people did not think of Australia as being vulnerable to tsunamis, there have been more than 50 recorded incidents of tsunamis affecting our coastline since European settlement.

He said most of these tsunamis resulted in dangerous rips and currents rather than land inundation.

“Tsunamis that affect the Australian coast are caused by subduction zone earthquakes in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Subduction zones are tectonic plate boundaries where two plates converge and one plate is thrust beneath the other,” Dr Davies said.

“In Australia, the northwest coast in Western Australia is more likely than the east or southwest coast to experience a tsunami due to its proximity to the Indonesia tectonic plate boundary, which has a long, seismically active fault line.”

However, the data also shows east coast of Australia could be affected by earthquakes in the Kermadec-Tonga trench in the southwest Pacific Ocean.

It also shows our east coast is at risk from violent tectonic activity in the New Hebrides trench, the Solomon trench, the Puysegur trench and even South America.

Dr Davies said impacts from the earthquakes in Indonesia have already caused damage in western parts of the country.

“The Geraldton marina in Western Australia received damage during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which occurred in Indonesia,” he said. “Impacts were also felt in the Oman port, near the Persian Gulf, which was over 6000 kilometres from the earthquake epicentre.”

The latest tsunami hazard modelling from Geoscience Australia updates data from a decade ago, and will be used in disaster risk management, evacuation plans and infrastructure planning.

Minister for Resources and Northern Australia, Matt Canavan, welcomed the new research.

“An earthquake oriented in just the right way could generate a tsunami that could have major consequences for Australia. Understanding the tsunami hazard and knowing what to do is critical,” he said. “The Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre ensures that all Australians have at least 90 minutes’ warning time to take action.”

The new data comes after a recent report claimed Sydney Harbour was at risk of inundation by a tsunami.

Scientists from the University of Newcastle highlighted a number of possible scenarios, including “dangerous whirlpools” at The Spit, killer currents and flooding at popular tourist hot spots such as Manly Corso and Sydney Harbour.

They say damaging waves could reach our shores in “two hours”, originating from underwater earthquakes and travelling as fast as jet liners.

“A Sydneysider will probably experience a tsunami in their lifetime,” said Dr Hannah Power, who co-authored the findings.

However, she suggested the city’s warning systems were ill-prepared — putting the public at risk.

“The way we think about tsunami needs to be reframed to reflect a realistic picture of a likely event,” Dr Power added.

A tsunami that hit Sydney Harbour in 1960 was significant.

“We could expect a tsunami of a similar size in the harbour once every 50 to 100 years,” Dr Power added.

— with Phoebe Loomes