Terrifying ‘hyperthreat’ coming for Australia as El Nino chance rises

Australia is no stranger to this danger – in fact, it’s almost become normal – but the brutal reality of what it signals is terrifying.

This isn’t normal.

An extreme heatwave is smothering much of Asia. That’s rare for this early in the year. It’s unusual that it’s already lasted a fortnight. It’s odd because it stretches across 12 countries from India, over mainland China and through to Thailand in the east.

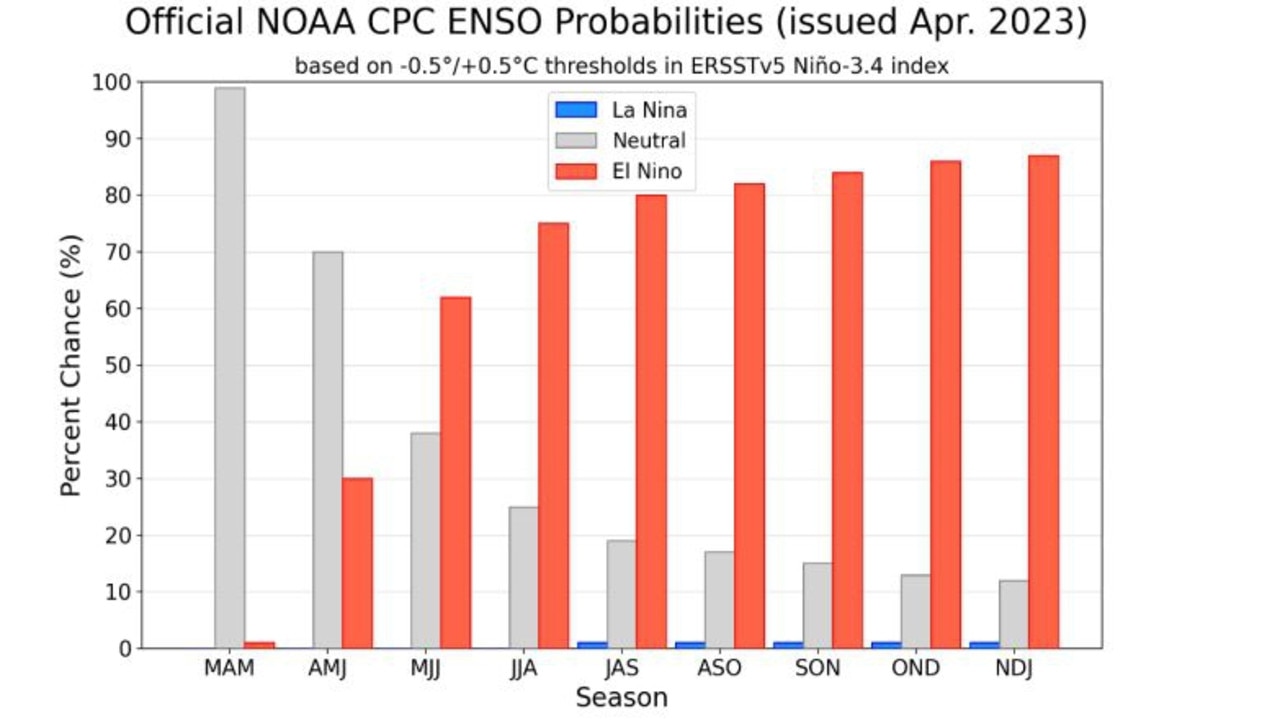

But it’s validating forecasts that another dry and hot El Nino climate event is on its way to Eastern Australia, with early indications pointing to it being particularly intense.

Climate research scientists have begun warning fishing industries, farmers and security services across South East Asia and the Pacific to expect troubled times ahead. Fisheries will be disrupted. Drought is probable. Weather systems will be stronger and less predictable.

Another crazy hot day in Asia

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) April 18, 2023

MYANMAR:44.5 Bagan

THAILAND:43.0 Phetchabun

LAOS:42.7 Luang Prabang hottest day in Lao history

34.5 Hottest April day in the mountain village of Pongsaly

VIETNAM:42.8 Muon La.

Record at Son La with 38.0

NEPAL:42.4 Bhairawa

Next days...worse ! pic.twitter.com/DFOpCzG6zl

This is rapidly becoming the new normal.

Which raises the question, what’s the next-level unusual?

Dr Greg Raymond of the Australian National University’s College of Asia & the Pacific put just such a scenario to a group of South East Asian and Australian defence officials.

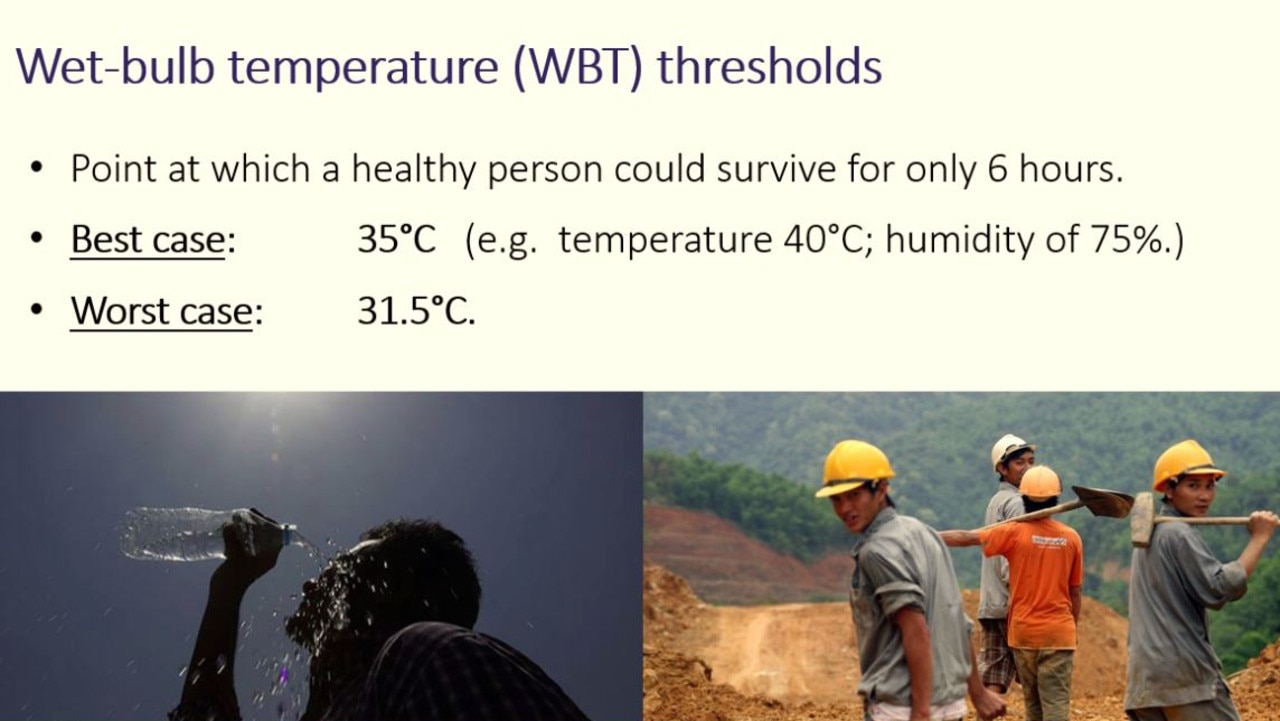

We know extreme heat is already killing people. But what if it persists for weeks on end? What if national electrical grids begin to collapse? What challenges would these officials face when desperate governments came demanding help?

They were divided into teams. Blue sought to preserve law and order and initiate a full spectrum of pragmatic responses. Brown emulated business, political, religious and media interest groups. And red sought to exploit the situation for their own benefit.

“I thought war gaming this scenario would be an interesting point of connection for them,” Dr Raymond says. “It’s more meaningful than having climate scientists give presentations.”

After four hours of high-intensity action and reaction, things didn’t turn out so well.

Clear and present danger

The consequences of global warming are no longer just charts and graphs scrawled on academic blackboards.

Thailand this week experienced its highest temperature since records began when the province of Tak exceeded 45C. Laos broke its highest-ever record with 42.7C.

Meanwhile, many Chinese provinces report monthly records toppling, with temperatures topping 35C. And 13 people died of heat stroke on Sunday alone in India as the country sweltered in the mid-40s.

Just in

— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) April 18, 2023

Hotter and hotter in China:today the temperature reached 42.4C at Yuanyang in Yunnan and 41.2C in Yuanjiang (similar name,not the same town),only 0.3C from the Chinese official national record in April.

The overheated air from SE Asia is now with full strenght in Yunnan. pic.twitter.com/8FlkbdKXzU

Climatologist and weather historian Maximiliano Herrera describes this event as the “worst heatwave in Asian history”. But these are historic times, with every year making history when it comes to climate-related events.

Climate security researcher Dr Elizabeth Boulton, a former Australian Army logistics officer, says we know worse is on its way.

When it arrives, people will want solutions.

And in a crisis, governments turn to their military, emergency services and intelligence agencies for answers.

“The civilian world might decide they really want to go for it, to do everything possible to avoid further dangerous climate change,” she says. “That’s when it will be the security sector’s job to ask, how do we protect you? How do we support you in that? And what do you need?”

Militaries are good at mobilisation, Dr Boulton says.

And that’s what the climate crisis needs. Not militarisation.

“People within the security sector are very motivated to protect their communities,” she says. “They have a sort of protective instinct. They’re citizens themselves, drawn from the wider community. And they know the taxpayer pays for the security forces. So they face quite a moral problem if they’re directed to defend a dangerous economic structure against a harmed populace.”

The ‘Green’

The participants of the ANU Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs security course come from Australia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia.

Many of those same countries are wilting under this month’s severe heatwave.

“In my view, there’s a little bit of complacency,” says Dr Raymond. “Climate change is not my sole focus.

“I look at all the more traditional security issues that may lead to military conflict. But what strikes me is that the effects we’re already seeing are worse than what was anticipated.

“It seems predictions have either been accurate or underestimated the severity of the impacts we’re seeing”.

So Dr Raymond and Dr Boulton gave the international group of officials a “Green” – slang for a military exercise briefing – for when a heatwave turns deadly.

It paints a picture of a searing September 2023. Cities across the equatorial regions suffer electrical grid failures. Pumps fail. Pipes crack.

The heat extends through October.

Fish start dying in rivers and lakes. Attempts at repairing infrastructure keep falling further and further behind.

Then people start dying of heat stroke and thirst.

Jakarta suffers 150,000 dead. Singapore loses 120,000. Kuala Lumpur must bury 210,000.

And there are enormous losses among cows, chickens, pigs and sheep.

Water and food rationing must be imposed. Emergency supplies must be sourced.

Bodies lay rotting in the streets. People are getting sick.

Angry and grief-stricken populations begin to protest. Looters target food and water sources. And global supply chains buckle under the strain.

Citizens demand an emergency response. They demand that immediate crises be addressed. They insist the long-term climate threat be reversed.

Amid the social uproar and suffering, the UN Security Council declares a planetary emergency.

Dr Raymond says the challenge was to force the participants to assess the implications of such a climate crisis with candour.

“In this scenario, the nations asked military commanders to lead the response,” he says. “There are plenty of precedents for that. Our previous federal government appointed a military commander to run the Covid-19 pandemic response. So it’s not completely far fetched.”

Confronting the hyperthreat

“The criminal groups moved in and became the security providers of choice,” Dr Boulton says of the war game’s outcome.

The Australian and South East Asian defence officials – at least those on the blue team – set out with good intentions and innovative solutions. But time was against them.

“They decided to override vested interests, to deal with the social dislocation, deal with the misinformation and policy settings in a very cohesive rather than piecemeal way,” explains Dr Raymond. “But they soon found out they were not the only force operating.”

Dr Boulton shares that assessment. “They were really trying to provide credible governance. And that is quite important, especially after the pushback we saw with Covid-19.”

But events quickly ran away from them.

Weather. Pollution. Politics. Lobby groups. Infrastructure. Supplies. Law and order.

In just one example, masses of hungry people resorted to cyanide fishing to get food fast. That provided one meal. But eliminated the next.

“All these problems can come together in one big hyperthreat,” Dr Boulton explains. “And because they weren’t ready with a contingency emergency framework, they had to start from scratch.”

Participants in the event, supported by experts from the Australian Army, quickly realised no one nation could look after itself.

They resolved to take a regional response.

“There’s a lot of proactive effort,” Dr Raymond says. “They’re talking about creating security forces focused on disaster response. They’re discussing integrating power grids.

“They’re thinking of ways to mitigate impacts in the short term, but also of ways to reduce the severity faced by the next generation.”

But Dr Boulton says the spark of civil unrest came when a popular news radio anchor cracked under the strain. “He absolutely unleashed at them (the emergency administrators) and said, ‘What the hell are you doing? We’ve got bodies on the streets, and you’re still sitting around talking about treaties? We need action now!’”

That’s when the transnational criminal groups and vested interests moved in.

“Desperate people became dependent on them because they would say, ‘We’ll give you food, we’ll give you water, we’ll patrol your streets and fishing grounds – if you do something for us in return.’

“Because they were more agile and faster moving, they thrived in this environment.”

After-action report

The terrible prospect of a nuclear winter saw the world unite in action to avert disaster. So why hasn’t the threat of a carbon summer elicited a similar response?

“I’m basically trying to do what a good security planner should do – anticipate,” says Dr Boulton. “Don’t react. Anticipate. Have a plan ready long before the crisis hits. The normal process of security planning is to have a whole set of contingencies developed and ready.”

She developed one such contingency, known as PLAN E which was published by the US Marine Corps. It provides an example of what an emergency response could look like.

When it comes to hyperthreats – where climate, pollution, economic, political and social strife converge – centuries worth of military logistics and mobilisation learning must be transferred to the civilian sector.

And Dr Boulton says history shows us the civilian world turns to security agencies for answers in any life-threatening crisis.

“They say we will need nuclear-powered submarines in 30 years as a contingency for a deteriorating regional security environment,” Dr Boulton says.

“We must apply that same sort of thinking towards what we will need in 30 years to survive the climate threat. We must start building those capabilities now to have them ready in time.

“Otherwise, officials will find themselves in the exact same position as our gamers now.”

And it’s a scenario with far-reaching implications. Crises create attitude change. Victims seek solutions. But also answers and accountability.

“When we look at who’s causing the whole climate ecological crisis, people are aware the fossil fuel industry has known about the fallout for a very long time,” Dr Boulton says. “I think we can say that we are now dealing with a different form of conscious hostile intent.

“A ‘knowingness’ of killing.”

And the backlash against cigarette companies knowingly selling cancer-causing ingredients is no point of comparison.

“Since we know harm is involved, since we know the threat to life is the result of conscious decisions – it can unleash a torrent of legal, political and citizen action,” she adds.

That means institutions must recalibrate their thinking as to what constitutes a security threat.

“I guess what’s controversial about my thinking is I’m actually saying economic actors have to come into this threat analysis because they are causing these harmful climate effects,” Dr Boulton says.

“We have to look at those foundational things, the big levers that are driving the chaos. We little people may keep up the recycling and change the light bulbs.

“But it’s not enough. It’s never going to be enough to undo the impacts of those big players and their larger gear settings.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel