Inside the state-of-the-art facility helping to save the Great Barrier Reef

It looks like something from a futuristic sci-fi movie, but the rows of glowing coral tell a far greater story.

It looks like something from a futuristic sci-fi movie, but the rows of glowing coral actually tell a real-life story of scientists’ desperate race to save the Great Barrier Reef from ecological disaster.

This is the world’s first Living Coral Biobank, which opened at the Cairns Aquarium earlier this week, billed as a “coral ark” to collect and protect hundreds of coral species from mass bleaching events and extinction.

The biobank is part of the Forever Reef Project and spearheaded by the Great Barrier Reef Legacy, and has already collected 45 per cent of the corals found in the reef – but scientists are racing against the clock to gather the rest.

“We’re going hard at this, we’re trying to pull off the unthinkable, but it’s also very achievable,” Forever Reef Project Leader Dr Dean Miller told news.com.au.

“We’re giving ourselves a two-year window to collect 400 species of coral in the reef, and we feel that beyond that we’ve probably almost missed our opportunity, because every coral bleaching event means we’re actually losing the most vulnerable corals and reefs.”

The project started in 2019, with just an idea of building a biobank to secure the biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef corals.

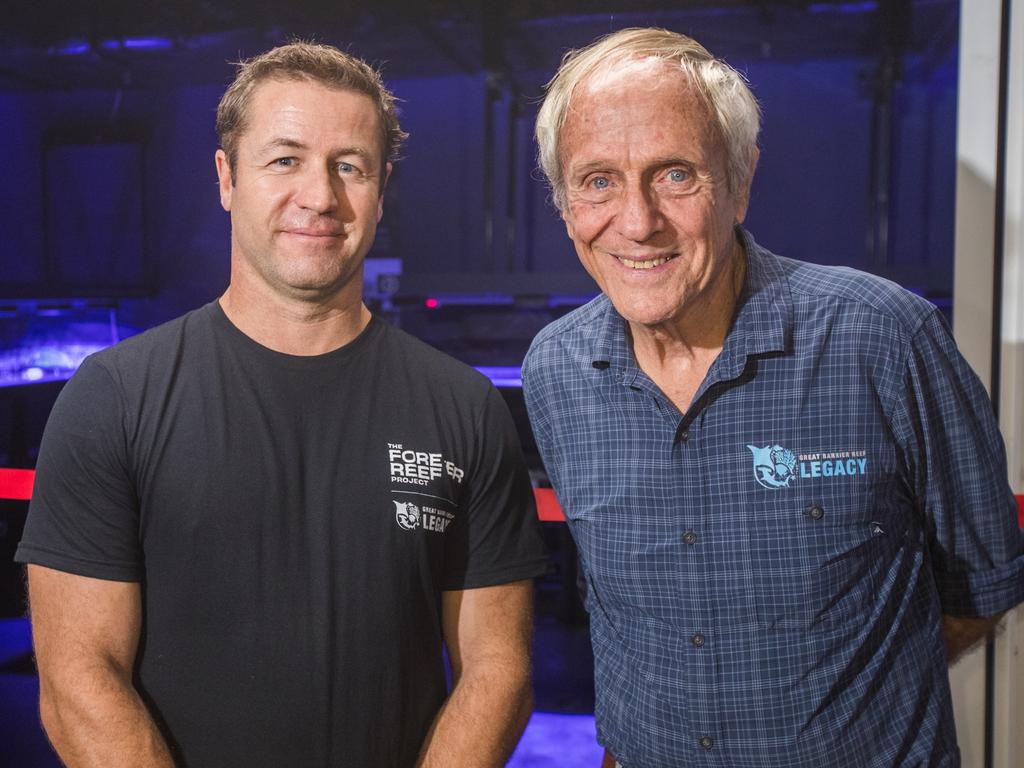

And with the help of the “godfather of coral” Charlie Veron – the former chief scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science – and almost $600,000 in private donations, the groundbreaking facility has come to life.

Dr Miller said “it took a village” to get the state-of-the-art facility off the ground so quickly because the industry professionals “tapped into” decades of work by amateur coral collectors.

“For the last 30 or 40 years people have been tinkering with marine tanks and keeping corals alive in their backyards, loungerooms, offices,” he said.

“And over that time, they’ve cracked the code and basically worked out how to build coral life support systems, and that’s what we’re tapping into.”

He said the team of scientists have “great confidence” they can collect and maintain the corals with more efficiently, thanks to the work of backyard scientists.

“Now it’s just a matter of getting out there and collecting the last remaining corals.”

The organisation is hoping to raise a further $500,000 to do so.

Adding to the need for efficiency is the increasing rate and severity of coral bleaching events, which first hit the Great Barrier Reef in 1998.

Dr Miller said in the last six years, alone, there have been “four mass bleaching events” that have “changed the landscape underwater forever”.

In March last year, a marine heatwave triggered a massive bleaching event that affected 60 per cent of the corals along the 500km stretch of reef between Innisfail and Mackay. It was the first time a heatwave had occurred in the cooler La Nina period.

And with the climate indicators changing to a hot, dry El Nino pattern, Dr Miller fears the next two summers are going to bring more, even worse bleaching events to the Great Barrier Reef.

The difficulty is, though, the Biobank wants to collect as many healthy, non-bleached living coral specimens as possible. Hence the time-crunch.

The Biobank will be used as a supply of live fragments, tissue samples, and genetic materials for research – including tests to genetically modify coral to be heat-resistant – education, and in case of dire extinction emergencies. It is like our own coral version of Norway’s Global Seed Vault.

“We hope we never have to use this collection to rebuild reefs, but it’s certainly looking that it may be a possibility,” he said.

“I don’t want to think about that, but I also need to because that’s why we’re doing this. We know that something potentially catastrophic is on the way, and that’s why we’re pushing so hard to get this job done by 2026.”

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted that bleaching would reduce global coral cover by 95 per cent, if global warming is kept to under 2 degrees. But if warming was kept under 1.5 degrees, coral cover would reduce by 70 per cent.

If all countries deliver on their most recent climate commitments and policies, we would still be on track for at least two degrees of global warming.

Dr Miller says that just proves the desperate need for the Biobank.

“If all the projections are correct – and so far they have been – we are set to lose huge expenses of coral reefs in the coming years,” he said, adding that the flip to El Nino only created more cause for concern.

“It would be a huge tragedy to lose something as special and as large as the Great Barrier Reef in our generation. I would be very embarrassed to turn to my daughter, who’s four, and say I’m really sorry but we didn’t do it. We didn’t save the Great Barrier Reef.”

Yet, despite desperately racing against the clock, Dr Miller was hopeful the “little battler” organisation could reach their target.

More Coverage

“We’re not saying this is the only way to save the Great Barrier Reef, but we know we can only do it together, like we built this Biobank,” he said.

“It really did take a village to raise this one, and there are hundreds of people who dug deep to help us out, a little battler non-profit organisation up in Port Douglas that is tackling one of the biggest conservation efforts in the world.”

It looks like something from a futuristic sci-fi movie, but the rows of glowing coral tell the story of Australian scientists’ world-first step to save the Great Barrier Reef.