‘Disaster waiting to happen’: Aussie cities face looming water crunch as population soars

Multiple Australian cities are facing a “disaster waiting to happen”, with experts warning the looming crisis could cost the country “billions”.

Record immigration has been blamed as a key driver of Australia’s housing crisis by a growing number of experts, but population growth will soon put increasing pressure on another, less-talked-about scarce resource — water.

Authorities, including state-based water utilities and federal agencies like the Productivity Commission and Infrastructure Australia, have long warned that population growth combined with climate change will pose a major challenge to water supply in Australia’s capital cities in coming decades.

And most of those warnings were made prior to the unprecedented post-Covid surge in migration that saw the country bring in more than the population of Canberra in one year.

“Sydney’s main dam, Warragamba Dam, supplies 80 per cent of Sydney’s drinking water,” said Leith van Onselen, co-founder of MacroBusiness and chief economist at MB Fund and MB Super.

“It was built in 1960 when Sydney’s population was just over two million. Now it’s 5.3 million and projected to grow to nine million by 2060. That there is a problem. At the same time you’ve got climate change. Whether you believe it or not, it says you’re going to have less rainfall and more evaporation. It’s a disaster waiting to happen.”

Indeed, Melbourne Water warned back in 2017 that the Victorian capital could run out of water before the end of this decade in a “worst-case scenario”.

The same year, analysis by water policy advisory Aither, commissioned by Infrastructure Australia, predicted average household water and sewerage bills would rise by 50 per cent in real terms — that is, not counting inflation — over the decade, from $1226 in 2017 to $1827 in 2027.

“The reason is we’re going to have to build desalination plants everywhere, which costs a lot more than natural water supply,” said Mr van Onselen.

By 2040, the average bill could be as high as $2553 in 2017 dollars. By 2050, that figure would be close to $4000, and by the 2060s bills would reach an astronomical $6000 per household.

Aither’s modelling also maps out an alternative scenario where “efficiency gains” cut down bills by around 10 per cent per year — but in both cases, water bills climb ever higher.

“A range of cost drivers including ageing assets, population growth, climate variability and change and higher costs to service greenfield development will continue to see household water and sewerage bills increase in real terms,” Aither’s report said.

The analysis was “based on projections of future revenue requirements to manage future cost drivers”.

“The impact of these changes on household affordability could be substantial,” Infrastructure Australia said.

“For many families, growth in bills of this scale could cause significant hardship. In the context of slow wage growth and rising cost-of-living pressures, including increasing bills across other forms of infrastructure, it is imperative that the urban water sector ensures services remain affordable. Managing emerging cost drivers should therefore be front of mind for governments, regulators and utilities alike.”

In its 2020 national water reform report, the Productivity Commission noted that a growing population was “putting increasing pressure on an already limited resource”.

“At the time of federation, Australia’s population was about four million people and just over one-third lived in capital cities,” it said.

“By 2019, Australia was home to 25 million people and over two-thirds lived in capital cities.”

Australia’s population in February officially ticked over 27 million, after record net overseas migration last financial year of 518,000 people.

The population is expected to nearly double in the next 50 years and by the end of the century, at present growth rates, could hit 100 million.

“No one believes 100 million is sensible for an arid country like Australia,” businessman Dick Smith said last month.

In December, the Albanese government vowed to bring migration back to a more “sustainable” 250,000 annually, after a projected peak of 375,000 this financial year.

But new figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) last week showing the highest January intake ever — a net increase of 55,330, more than double January 2023 — suggest the country is on track to beat last year’s record.

In its 2020 report, the Productivity Commission noted that capital cities accounted for four-fifths of population growth in the prior year, a trend that has accelerated since.

“In major cities where readily available supply sources have already been accessed, ongoing population growth is likely to create significant pressure on increasingly limited water supplies,” it said.

“With the exception of Darwin, all of Australia’s capital cities are located in southern or eastern parts of Australia, which are regions likely to see future declines in water availability as the climate changes. Major supply augmentations will be needed to meet increasing demand.”

The worst-case scenario modelled in 2017 by Melbourne Water could see high demand outstripping low supply by 2028 without further supply augmentation for the city.

“Uncertainty in the underlying climate and demographic models, however, means that Melbourne’s water security may last until well beyond the middle of the century,” the Productivity Commission said.

Under Melbourne Water’s medium demand and medium climate change impact scenario, Melbourne would see shortfalls by 2043.

“Overall, urban water providers are likely to face significant pressures to augment and better manage water supplies,” the Productivity Commission said.

“Here, too, past experience contains lessons for future reform settings and contributes to the case for National Water Initiative renewal. For example, instances of rushed investments into desalination and water recycling, and poor selection of major rural water infrastructure with attendant costs for taxpayers, highlight the need for best-practice planning and investment decision making.”

Soaring household bills outlined by Infrastructure Australia are partly due to higher costs of supply augmentation via technologies like desalination.

Put simply, all of the cheap and easy sources water for Australia’s capital cities have already been built — everything from here just gets more expensive.

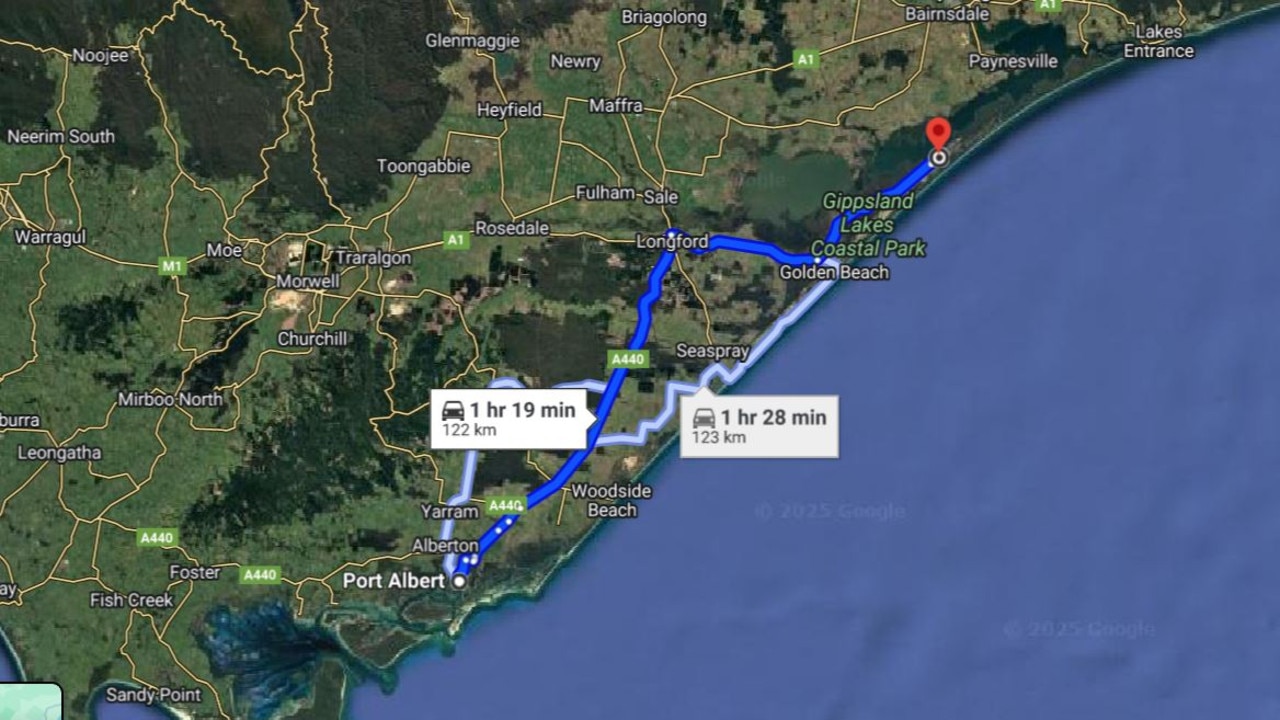

The only exception is the Mitchell River in Victoria’s Gippsland region — the largest river without a dam in southeastern Australia, not for want of trying and fierce debates over many decades.

During the Millennium Drought from 1996 to 2010, states controversially spent $11 billion building large desalination plants, resulting in increases in customers’ bills or taxes to keep the hi-tech operations ticking over even as rainfall resumed and dam levels surged to nearly 100 per cent full.

Desalination costs about four times more than standard water supplies.

Sydney’s privately owned desalination plant at Kurnell can provide up to 15 per cent of the city’s total water use when operating at full capacity, supplying about 1.5 million people with an average of 250 million litres a day.

“Running the plant for the 12 months up to March 2023 cost the average household $25.58 a year,” Sydney Water says.

The Kurnell plant supplies water as far west as Canada Bay, but relying on desalination into the future will pose additional challenges as urban sprawl marches inland.

“Think about it logistically — western Sydney is the main dumping ground for migrants 30 to 50 kilometres from the coast,” said Mr van Onselen.

“Somewhere you’re going to have to build a battery desalination plant to get water from the coast, and build whole pipelines to somehow ship it into western Sydney against gravity. You’ll have to build tunnels, you can’t put it through people’s backyards. Water’s really heavy, to push water uphill you need a lot of energy. It’s going to cost billions.”

Mr van Onselen claimed authorities never gave serious attention to looming water supply issues brought on by immigration.

“We’ll just mumble our way through while they continue to make the problem worse by fire-hosing unbelievable numbers of people [into the cities] who all use water,” he said.

“Basically we’ve got enough natural water supply for a population of X, but now we’re doing 2X and going to 3X. It’s kind of basic but at the same time people just ignore it because they don’t want to hear about it.”

In a statement, a spokesman for the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water said the Australian government “recognises that a sustainable and water secure future, in the face of a range of challenges including population growth, is dependent on reliable and modernised water infrastructure”.

More Coverage

“That’s why we continue to co-fund water infrastructure projects that support our communities,” he said.

“The government is working with all states and territories to develop a new national water agreement, building upon the 20-year-old National Water Initiative framework, which prioritises achieving water security in the face of climate change and increasing demand, and elevating First Nations water interests and involvement in decision making.”