2010s the warmest decade in recorded history as World Economic Forum members grow concerned over environment

The previous decade was the hottest and driest ever, but the areas of greatest concern where the heat is rising the quickest could go unnoticed.

The 2010s will go down in history as the warmest in recorded world history, at least for the next ten years.

It should come as no surprise to us Australians, having spent 2019 sweltering through heat higher than 1.5 degrees above average in the hottest and driest year on record, which was also the second warmest globally.

It was a fitting way for us to end the decade, which previously featured our hottest and driest year record being broken in 2013.

Every year that followed since then is in the top 10 hottest and driest for our country.

The only pre-2005 year in the top 10 was in 1998, according to the Bureau of Meteorology’s latest annual climate statement.

The story is largely the same around the world.

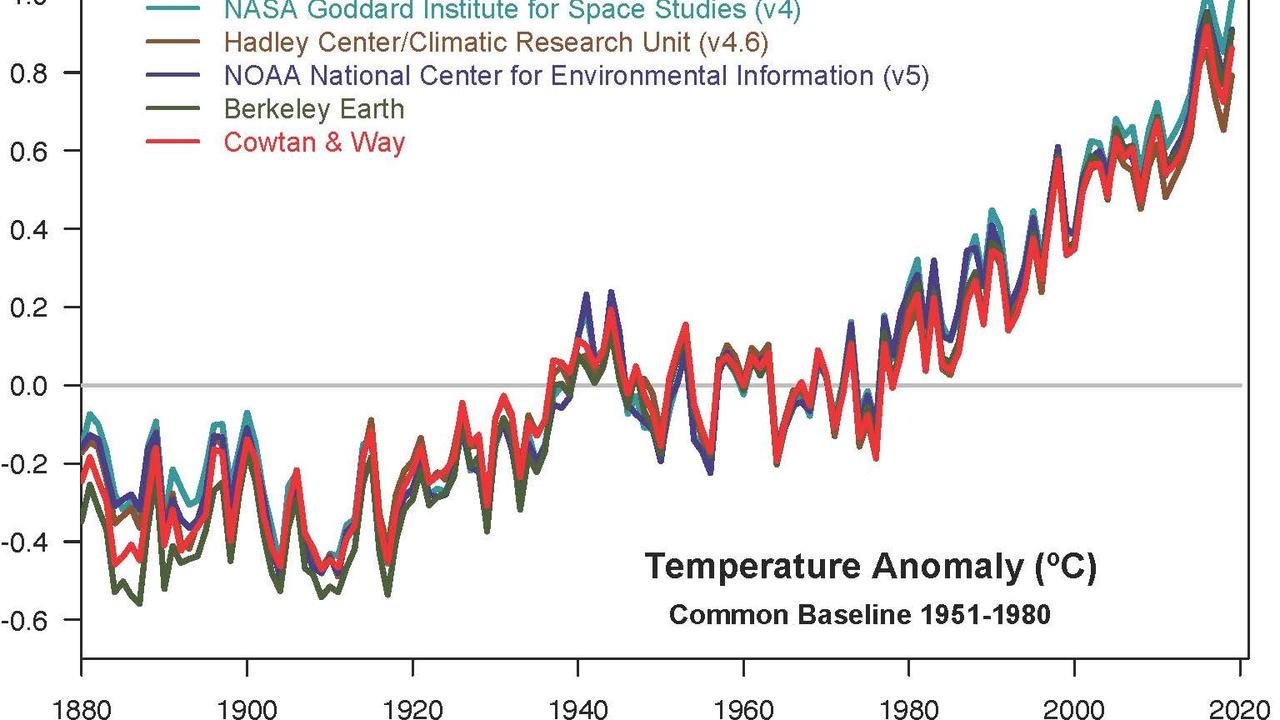

Newly released analyses from the United States’ NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) compared data from five different sources to map the simultaneously warming and drying climate on a global scale.

Despite mild and to be expected variations in the actual raw numbers, all sets show the same peaks and valleys.

They all show rapid warming in recent decades.

They also show the past decade was the warmest.

“The decade that just ended is clearly the warmest decade on record,” said the director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) Gavin Schmidt. “Every decade since the 1960s clearly has been warmer than the one before.”

The GISS is affiliated with Columbia University’s Earth Institute and housed at its New York City campus, where it studies changes in the environment on a global scale.

RELATED: Oceans record warmest temperatures ever for fifth year in a row

But of course we don’t really need scientists to tell us temperatures are getting higher and the world is getting drier.

We know it’s been hot and dry, we experience the weather daily as heat records tumble and drought forges cracks in the ground throughout the cities, suburbs, and regions we live in.

Worryingly, the places the world is warming fastest are far less noticeable to the average person, and could have even more dire impacts on the world at large.

The virtually unpopulated Arctic region has been warming at a rate three times faster than the rest of the world since 1970.

Greenland and Antarctica continue melting, as ice enters the ocean and causes sea levels to rise.

The sparsely populated US state of Alaska just had its warmest year on record, with a 2019 average temperature more than 3 C higher than the average from 1925 to 2000.

While the climate has passed several “tipping points” already as repeated calls from scientists about a changing global climate go virtually unheeded for nearly five consecutive decades, as the predicted impacts are being increasingly felt, there are signs things are starting to change as more people and – crucially – industries grow concerned.

THE COST OF DOING NOTHING

The World Economic Forum’s recent Global Risks Report for 2020, which polls around 800 members of the Forum on what factors they think pose economic risks for the upcoming year, revealed environmental issues the most likely to pose global risks to the economy.

Extreme weather, climate action failure and natural disasters were the top three most likely, echoing last year’s survey.

But biodiversity and human-made environmental disasters bumped out data fraud or theft, and cyberattacks as the most likely risks to round out the top five.

Climate action failure was the number one risk in terms of the impact it would have on the world economy, returning to the top spot it held in 2016 after being replaced by weapons of mass destruction in the past three years (which would obviously have a devastating impact but hasn’t been considered much of a likelihood in this or the previous 12 yearly reports).

It was the first time environmental, or indeed any category of issues dominated the top five concerns, according to World Economic Forum president Børge Brende.

"The cost of inaction today far exceeds the cost of action."@borgebrende, president of the @wef, says it's past time for world leaders to take climate change seriously pic.twitter.com/WooD7rAGQw

— QuickTake by Bloomberg (@QuickTake) January 15, 2020

For the first time, all the top issues in the Global Risks Report are related to global warming. Extreme weather, major natural disasters and loss of biodiversity are set to dominate the next decade. https://t.co/LjIohKgflI

— Børge Brende (@borgebrende) January 15, 2020

It was also the first time the Forum included results from its Global Shapers Community, made up of “young people driving dialogue, action and change”.

The “Shapers” were more worried about environmental (and indeed most other) factors than the multistakeholders were, suggesting that young people are more concerned about the current and impending impacts of climate change than older generations that didn’t grow up hearing about them and won’t be alive to deal with them.

“We note with grave concern the consequences of continued environmental degradation, including the record pace of species decline,” Mr Brende noted in his preface to the report. “Respondents to our Global Risks Perception Survey are also sounding the alarm … but despite the need to be more ambitious when it comes to climate action, the UN has warned that countries have veered off course when it comes to meeting their commitments under the Paris Agreement on climate change,” he said, without mentioning Australia directly.

VEERING OFF COURSE

The argument put forward at a recent UN conference by our Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction Angus Taylor went over like a lead balloon among other nations.

He wants Australia to be able to use “carry-over credits” from exceeding previous targets to “meet and beat” its Paris commitments, as part of the “strong, credible and responsible commitment” the Department of the Environment and Energy claims our government took to the table.

The carry-over credits, if Australia is allowed to use them, would slash our need to reduce emissions by more than half.

Mr Taylor has a long history of opposing renewables, instead pushing for the reduction of emissions through “other means”, such as liquefied natural gas (LNG).

LNG produces around 40 per cent less emissions than coal, as opposed to renewables, which produce around 100 per cent less.

Mr Taylor also has a poor track record when it comes to accurately representing numbers, and is currently under investigation by the Australian Federal Police for using a fake document with phony figures to criticise the City of Sydney Council for daring to ask the Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction do something to reduce emissions.

He later apologised to Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore, a week after trying to dismiss the scandal as a “conspiracy theory”.

Australia is responsible for around 1.3 per cent of global emissions, which makes us one of the highest per capita emitters.

That’s before you factor in the emissions resulting from manufacturing products in other countries and importing them into Australia, or from the fossil fuels dug out of our ground and sent overseas by fossil fuel companies.

Some of those corporations are among the 100 blamed for more than 70 per cent of global emissions since 1988 by a 2017 study.

That study quantifies the end emissions of the products and services those corporations sell and not just the emissions from producing the fossil fuels in the first place.

Those reluctant to do anything to combat a changing climate, such as gradual decarbonisation of industry and increasing renewable energy, often cite the cost of doing so, even as renewables become significantly cheaper.

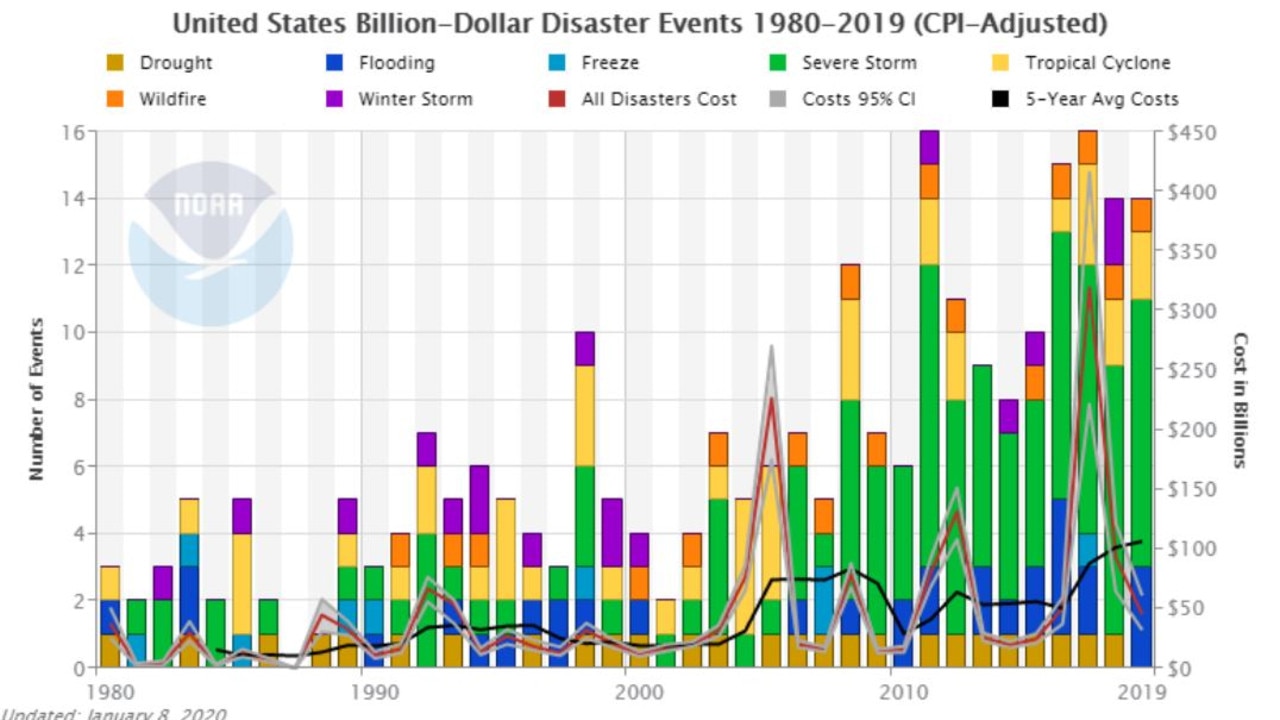

But according to NOAA’s data for the US, the cost of dealing with natural disasters, which are exacerbated if not directly caused by climate change, has risen along with the temperature, with the previous decade also the most expensive.