Australian archaeologist reveals the most frightening thing in Chernobyl

The only archaeologist to stand in the ruins of the world’s deadliest city is Australian — and he learned some valuable lessons while inside.

As Australian archaeologist Robert Maxwell stood in the ruins of the Chernobyl exclusion zone during his first field trip to Pripyat, he had one pertinent question for his guide.

“What’s the most dangerous thing here?”

“My guide turned to me and said, ‘The wild pig. If you see a pig, climb a tree.’

“I said, ‘But the trees are radioactive!’ and he replied, ‘Yes, but they’re less dangerous than the pigs. A tree will not gore you,”’ Maxwell said.

Last Friday marked 33 years since the Chernobyl accident, 33 years since the biggest nuclear energy disaster in history.

But, today, Pripyat is a place of hope.

RELATED: Eerie photos show Chernobyl 33 years after disaster

According to Maxwell, the very fact that animals are thriving in the exclusion zone proves the impact of the explosion is much less than people realise.

Even UNSCEAR (The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation) claims that aside from an increase in thyroid cancer, “there is no evidence of a major public health impact attributable to radiation exposure”.

Today Chernobyl is the largest tourist drawcard in modern Ukraine, with more than 60,000 visitors last year — but a trip to the exclusion zone is not without its risks.

If the radioactivity won’t kill you, there are living creatures that possibly will.

Ukrainian officials estimate the area won’t be safe for human habitation for at least 20,000 years.

THE ACCIDENT AND THE ANIMALS

In the aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion of 1986, the very word Chernobyl became forever synonymous with meltdown, disaster and total devastation.

Reactor number four exploded on April 25 and, two days later, the entire city of Pripyat, northern Ukraine, was evacuated.

Of the 50,000 residents that fled the city, few had any idea that the evacuation would be permanent, with abandoned homes, shops, offices and schools frozen forever in time.

Maxwell said it’s one of the surreal aspects of being in Pripyat, when you realise that when the humans retreated, the animals entered.

“In Northern Ukraine and parts of Belarus, if you’re alone on a road, there’s a chance a wild boar will get you. If the boar doesn’t get you there’s a chance the wolves will take you and, if the wolves don’t take you, the bears can get you,” Maxwell said.

“One day I was wandering around Pripyat where the population was once 50,000. That day, there were only three people — myself, my driver and my guide. I was going into abandoned apartment buildings and there was a real fear of turning a corner and coming across a wolf or a bear and surprising it.”

“It’s an interesting primal experience because you suddenly feel what your deepest ancestors would have felt; the sense you could be taken by a scary animal at any point. But you’re in such a modern environment of concrete and supermarkets and abandoned pianos.

“It’s a real clash of time periods. You get a sense of time travel when you’re in the exclusion zone.”

A CHERNOBYL OBSESSION

Sydneysider Robert Maxwell is the only archaeologist who has ever worked at Chernobyl, completing two field excursions at the exclusion zone, in 2010 and 2012.

Describing himself as a “Cold War Kid” Maxwell, who lives in Sydney, has been both fascinated and obsessed with Chernobyl since childhood.

When he began studying archaeology, the decision to choose Chernobyl as his PHD was an easy one.

“I grew up with a sense of nuclear awareness. We were all scared we’d be blown to smithereens. And then something scary happened in Europe in 1986 and it meant that the media went crazy. Chernobyl is something I have an early childhood memory of but now, as an adult, it was interesting to look at because it became such a ‘bogey man’ in the after effects,” Maxwell said.

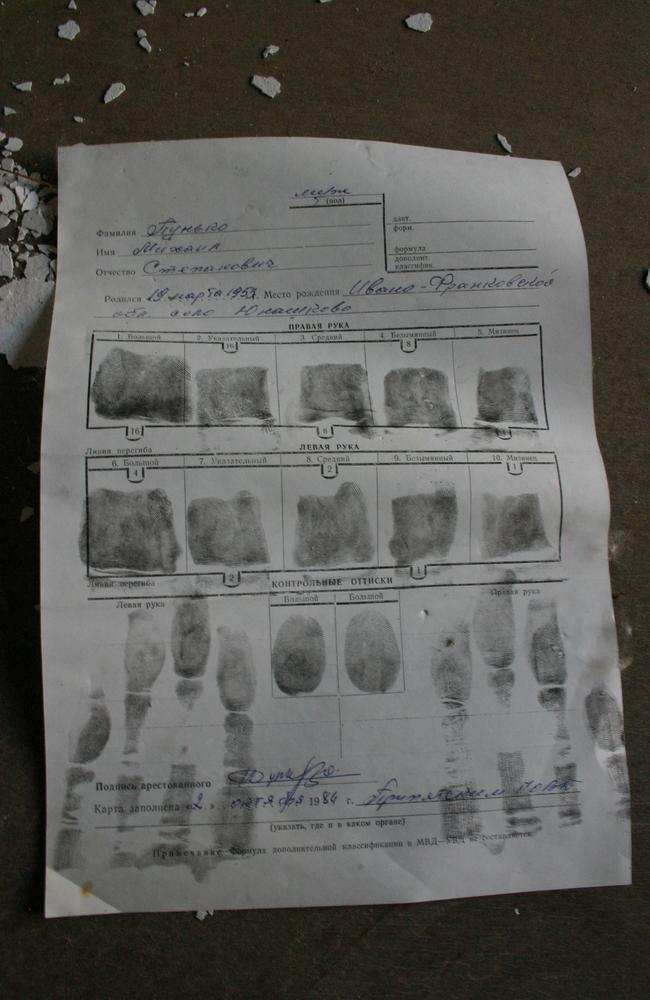

“As an archaeologist I went to Chernobyl with a dedicated methodology that I wasn’t going to manipulate anything, I wasn’t going to manipulate objects from the ground. I was only going to record what I saw as I saw it, then visually excavate it object for object, context for context, to figure out what it tells you about 1986, as well as our response to the events of ‘86.”

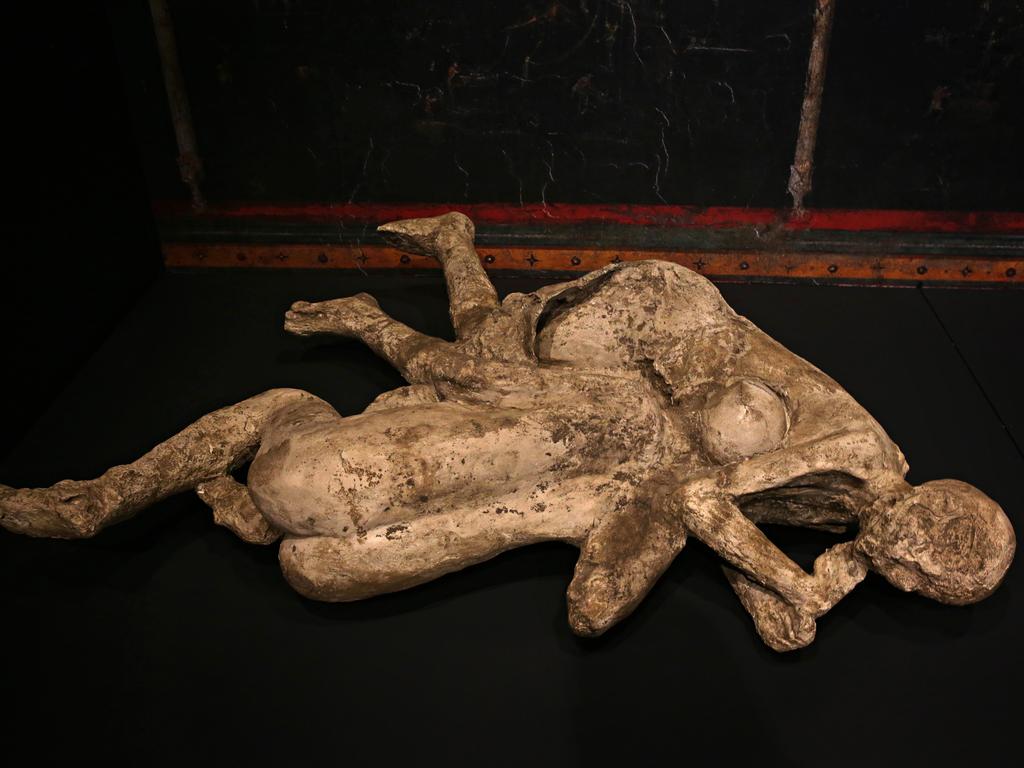

THE POMPEII CONNECTION

Maxwell has an incredible wealth of knowledge about Chernobyl, a place he is truly passionate about.

When he gives lectures, he likes to compare Pripyat with the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, devastated by volcano Mount Vesuvius in 79AD.

“Pompeii had a relationship with Mount Vesuvius in a similar way the city Pripyat had with the plant at Chernobyl.

“Pompeii was a resort town, a largely tourist-driven town. With its mountainous views and volcanic sand, it got all the rich Roman tourists to the seaside to spend a lot of money and go home again. It was like a Gold Coast town,” Maxwell said.

“When Vesuvius erupted, the ash covered Pompeii and thus preserved it until the antiquarian excavations of the 18th Century.

“In Chernobyl there’s the example of the plant and then the city of Pripyat,” Maxwell said.

“Pripyat was what Soviets referred to as an ‘atomograd’ and it was built with the express reason to house and feed and care for the working population of the plant. And so, they had this binary relationship in the same way that Vesuvius and Pompeii had a relationship.”

“All the other atomograds have evolved and moved on and become post-Soviet and got McDonald’s and 711s whereas, because of the disaster, Pripyat actually sealed its own survival because it became this entity in the landscape that nobody wanted to interact with because it was considered to be so lethal.”

THE ROLE OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN CHERNOBYL

Working in Pripyat, Maxwell spent time analysing the exclusion zone and the disaster in terms of settlement decline.

“Settlement decline is something that happens across the millennia across every period you could name. I thought it’d be interesting to apply what we call a ‘contemporary archaeology study’ using the tools of archaeology in its bare bones, recording analysis and observations in the field,” Maxwell said.

“Archaeology is very useful in places like Chernobyl, Detroit and Fukushima because it tells you what occurred in the ground, what’s happened since and how we view those places.

“The punchline of my study is that there really isn’t such a thing as an abandonment. And, when we look at Chernobyl as a thriving place for tourists, and a thriving place for animals, the idea of abandonment takes on a new meaning.”

Maxwell describes walking into abandoned homes, shops and schools overcome with the strange feeling of being in a place where time literally stood still.

“I walked into a school and, from a distance, it looked like the floor was covered with leaves. But, as we got closer, I realised that the ground was covered with gas masks. What happened was that during the Cold War, people stockpiled gas masks due to a fear that they might be bombed by the Americans.

“With the Chernobyl explosion, these gas masks were brought up from somewhere, maybe a basement, and given to everybody,” Maxwell said.

“But, clearly, these were tossed away once it was realised the masks were useless and people fled.”

THE CHERNOBYL TOURISM INDUSTRY

There’s an official website for anybody who is truly keen to be a tourist in Chernobyl.

Put simply, if you can pay to go to Chernobyl, you can be there. Maxwell said any keen tourists must be prepared for a very regulated experience.

“It involves going through multiple checkpoints, a couple of different information briefings by some official tourist authorities. There are several different legislative and customs-related hurdles you’ll have to cross in order to get into the zone,” Maxwell said.

“But, once you’re in there, the sort of access you paid for will determine where you can go. Basically, you can go anywhere the government says it’s okay for you to go in the zone. But when I looked into the Belarus access, it was extremely difficult to just get access to the country. But there is no exclusion zone and no checkpoints on the northern side of the disaster. And now that it’s 2019, I think the larger question is, ‘What has the effect been beyond Ukraine, into Belarus?’ That’s still a largely unknown factor, whereas Chernobyl is now quite a well-studied resource.”

THE FUTURE OF CHERNOBYL

Moving forward, Maxwell is greatly concerned that the Chernobyl exclusion zone isn’t adequately protected.

It’s essentially made up of a series of unique structures that speak of a period that is starting to fade from collective memory, or a time when the nuclear threat was very real.

“In the wake of what’s been left behind, Chernobyl is a very important series of buildings and artefacts and what we call ‘evidence of lifeways.’ It’s important to protect the area because if the Ukrainian government or a private company wanted to demolish the structures of Pripyat, then they could because there’s nothing to stop them,” Maxwell said.

“It’s one of the most important archaeological sites of the 20th Century and what we’re facing is a double edged sword. What do we want to do? We want to remediate the area and make it as safe as we can, but we also want to preserve the heritage of our parents’ and grandparents’ generation.”

“Chernobyl and the city of Pripyat are so important they require UNESCO listing, or some form of international heritage protection because otherwise they are at risk. Even winter snow on the concrete roof tops is damaging because, when the snow melts, it gets into the concrete and the buildings literally fall to pieces. Between my first and second field seasons there were four buildings that just crumbled. So, my concern is they won’t be there to bear witness to history unless we protect them.”

HOW DANGEROUS IS CHERNOBYL TODAY?

Maxwell believes there is still a lot of conjecture about what radioactive impact Chernobyl has had on the world.

Some experts argue that the impact is larger than what people are wanting to acknowledge.

But, from everything that Maxwell has seen and experienced, he maintains the opposite is true.

“I’d argue that the effect is much less than people realise because the zone is teeming with wildlife leading very normal, healthy lives. And the wild boar in the Chernobyl exclusion zone are now back to their Medieval levels. It’s the only place in Europe where that’s the case,” Maxwell said.

“Due to remediation of large areas of the CEZ in the 1990s, there are entire regions where the background radiation is negligibly higher than that of Sydney. The same goes for Fukushima Prefecture in Japan.”

“Of course, if you go strolling into the heart of either reactor vessel you’ll fry yourself and die. But the actual lived experience of the Chernobyl disaster, I would argue, has more to do with psychological disaster than it does radiological disaster.

“The most harrowing aspect of working in fields of trauma like Chernobyl is the sense of life interrupted and the forced relocation of the population.

“That is the true horror of Chernobyl.”

— Continue the conversation with Robert Maxwell on Facebook or Instagram

— LJ Charleston is a freelance features writer | @LJCharleston