Are you one of the 2.5 million Australians doomed this summer?

It’s set to be a scorching summer, but if you’re one of the 2.5 million people living in this area, it’ll be even worse – and it’s your fault.

While vast parts of the country brace for a sweltering summer, conditions will be especially gruelling for millions of Australians in one area – and things are set to get dramatically worse.

Western Sydney is ground zero of an extreme heat crisis that experts warn will cause financial distress, serious illness and even cost lives.

The region, home to about 2.5 million people and projected to grow by 400,000 more by 2030, can be up to 10C hotter than the eastern suburbs during a heatwave.

The area is naturally hot as it’s too far inland to get coastal breezes and also low-lying, which traps hot air, but “absolutely mad” human decisions make the situation worse.

City planner Samuel Austin said choices about the style of homes built in the west and the design of the suburbs they sit in have doomed Western Sydney to a blistering future.

“Fifteen or so years back, having a dark-coloured roof became really popular,” city planner Samuel Austin said.

“They look stylish and modern, so people loved them. Just about every roof in Western Sydney is black. The problem is, that’s a 150sq m surface sitting in the sun all day attracting and absorbing huge amounts of heat.”

Research shows a dark roof can be 40C hotter on its surface than air temperature and experts have noted instances where a roof cavity reaches 50C on a hot day.

At the same time as the dark roof trend took off, land sizes started to shrink rapidly, Mr Austin said

“They’re about half what they were 50 years ago, but the houses we build have stayed the same size.”

Tiny backyards aren’t capable of holding many, if any trees.

Out the front, developers make verges as small as possible to maximise the land they can sell, leaving even less room for suitable greenery.

“You might drive around and you see these tree saplings on the street and think: ‘Oh, one day that’ll be a big beautiful tree.’ Nope. It won’t happen. They’re not species that will ever get to the height needed to offer shade.”

Research shows a house that’s 30 to 40 per cent shaded by trees can be five to six degrees cooler inside.

A region getting hotter by the year

Extreme heat days in Western Sydney, an event defined as being when temperature rises above 35C, number an average of nine per year at the moment.

In the midst of a heatwave in January 2020, Penrith was the hottest place on earth as the mercury notched 48.9C.

That’s around the time Emma Bacon founded Sweltering Cities, a not-for-profit working with those impacted by extreme heat.

“It was inspired by stories from people in the west who were struggling that summer – people who couldn’t afford to turn on the aircon … people feeling sick in the heat, people sitting in their cars with the aircon on,” Ms Bacon said.

“People think this is an individual experience – a hot home is their problem. But one-in-10 Australians live in Sydney’s west, so it’s a big problem for lots of people.”

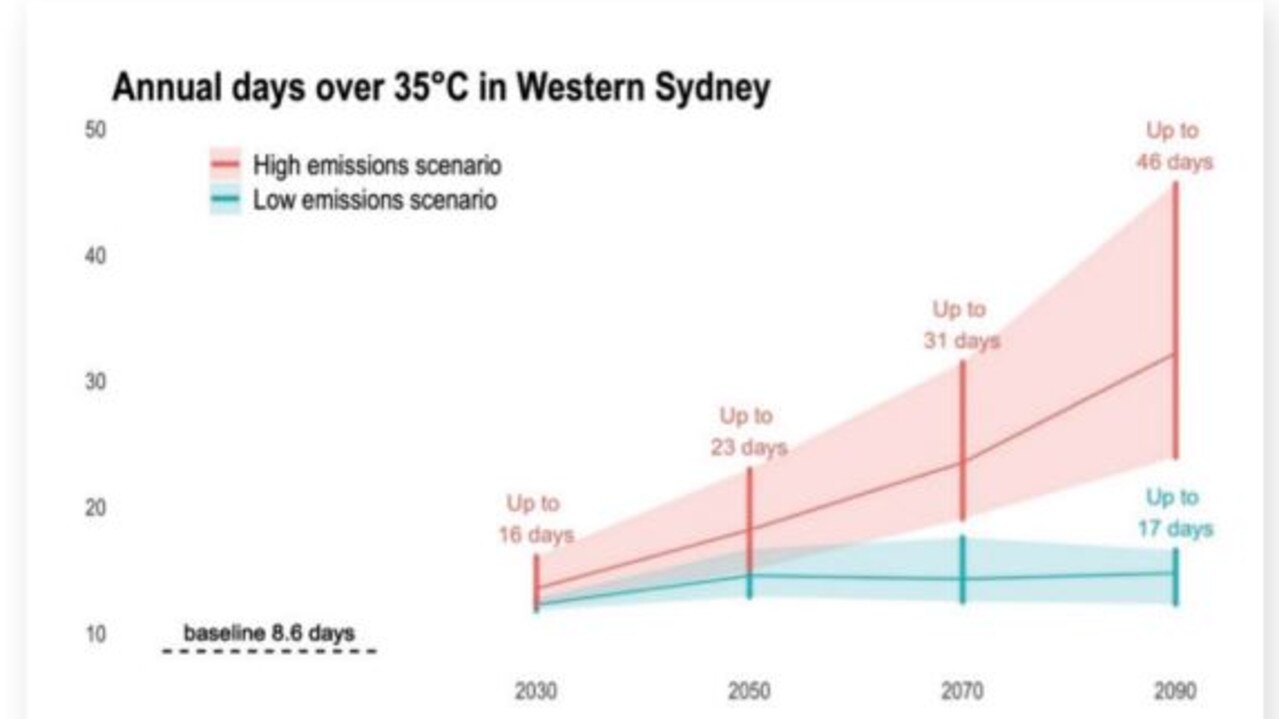

Western Sydney will only get hotter over time, with research by the Australia Institute forecasting a sharp increase in the frequency and severity of extreme heat days.

Its study looked at Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO climate scenarios for 12 federal electorates in the region to project extreme heat likelihoods.

“Under a high emissions scenario, Western Sydney could experience up to 46 days of extreme heat annually by 2090,” the research found.

“This is a five-fold increase from the historical average of just under nine days of extreme heat per annum.”

But impacts will be felt much sooner, with the number of extreme heat days projected to reach 16 per annum by 2030, almost double the current rate, and up to 23 days by 2050, according to the modelling.

“Alarmingly, annual figures for Lindsay are already outstripping these future projections,” the report revealed.

“Data from the Penrith Lakes BOM weather station shows there were 44 days over 35C recorded in both 2018 and 2019 – outstripping the projection for average days over 35C in 2090 under a high emissions scenario.”

A costly and deadly scenario

Living in an urban heat island – a location hotter than somewhere nearby – results in a greater reliance on airconditioning, putting pressure on household budgets via high electricity costs.

“It’s a common experience for people to second-guess what they can do to stay cool, whether it’s turning on the aircon or even sometimes turning on a fan,” Ms Bacon said.

“With cost-of-living pressures combined with a housing affordability crisis, just imagine what this summer going to be like.”

As well as an economic cost, rising heat poses a serious health risk and 35C is considered by experts to be the threshold for what is acceptable.

Higher temperatures significantly impact the body’s ability to cool down, which can cause dehydration and heatstroke.

Vulnerable people, including those with pre-existing health conditions and the elderly, are at risk of death.

“When hot days are combined with hot nights, the body has no opportunity to cool down and recover,” the Australia Institute research noted.

“As a result, mortality rate from heat increases nearly 20 per cent when the average temperature across a 24-hour period is above 30C.

“Extreme heat has already been shown to kill more people in Australia than all other natural disasters combined.”

In addition, extreme heat has non-human impacts on critical infrastructure like energy grids and public transport.

And a 2021 report by NSW Treasury estimated that by 2061, the state could lose 2.7 million working days every year due to reduced worker productivity in construction, manufacturing, mining and agriculture due to heat.

Authorities know it’s a problem

In 2021, the NSW Department of Planning and Environment was instructed by then-Planning Minister Rob Stokes to ban dark roofs on newly built homes.

As a kind of pilot project, a Development Control Plan for the new suburb of Wilton in Western Sydney, set to be home to 9000 dwellings when complete, prohibited the use of dark roof materials in favour of lighter and more reflective alternatives.

Mr Stokes told Nine newspapers at the time: “The need to adapt and mitigate urban heat isn’t a future challenge – it’s already with us.”

Not long after, he was replaced in his role by Premier Dominic Perrottet. The man elevated to minister, Anthony Roberts, swiftly dumped the ban plan.

“We were hugely disappointed,” Ms Bacon said.

“New regulations around light-coloured roofs will have a positive benefit not just for Sydney but for people saving money on aircon, for their comfort in summer … it’s an incredible alternative.”

The more black roofs in a suburb, the hotter the whole neighbourhood will be, she said.

“We shouldn’t be designing for a climate that no longer exists. The fashion needs to catch up to that reality.”

An updated version of BASIX, the NSW Building Sustainability Index, was released recently and contained a range of measures to increase efficiencies in dwelling design and construction.

“It addressed a lot of these issues,” Mr Austin said. “But the government suspended it, claiming it will increase build costs, which is a bad thing in a cost-of-living and housing crisis.

“The irony is that those exact types of fixes can actually save households about $1000 a year.”

There’s time to correct course

The Australia Institute said failing to act both the causes and impacts of extreme heat “could lock Western Sydney into devastating increases” in coming years.

“That could transform the growing region into a dangerous place to live and work. This is not inevitable with an effective response.”

Hannah Melville-Rea, a researcher from New York University who examined the Western Sydney scenario, said reducing emissions should be a priority.

“Reducing emissions is the difference between 1.5 months and 17 days of extreme heat per year in Western Sydney,” Ms Melville-Rea wrote in an article for The Conversation.

“At the local level, we need to design our cities and homes to protect vulnerable members of the community. Lighter coloured roofs reflect heat, and can reduce indoor temperatures by 10C during heatwaves.

“Increasing green spaces, ensuring bus stops and parks are adequately shaded, and providing affordable access to airconditioning are also crucial steps to making Western Sydney safe.”