Olympics’ Big Air ‘dystopian hellscape’ is not what it seems

Eileen Gu earned plenty of praise earlier in the week when she won her first gold medal but the location stole plenty of her spotlight.

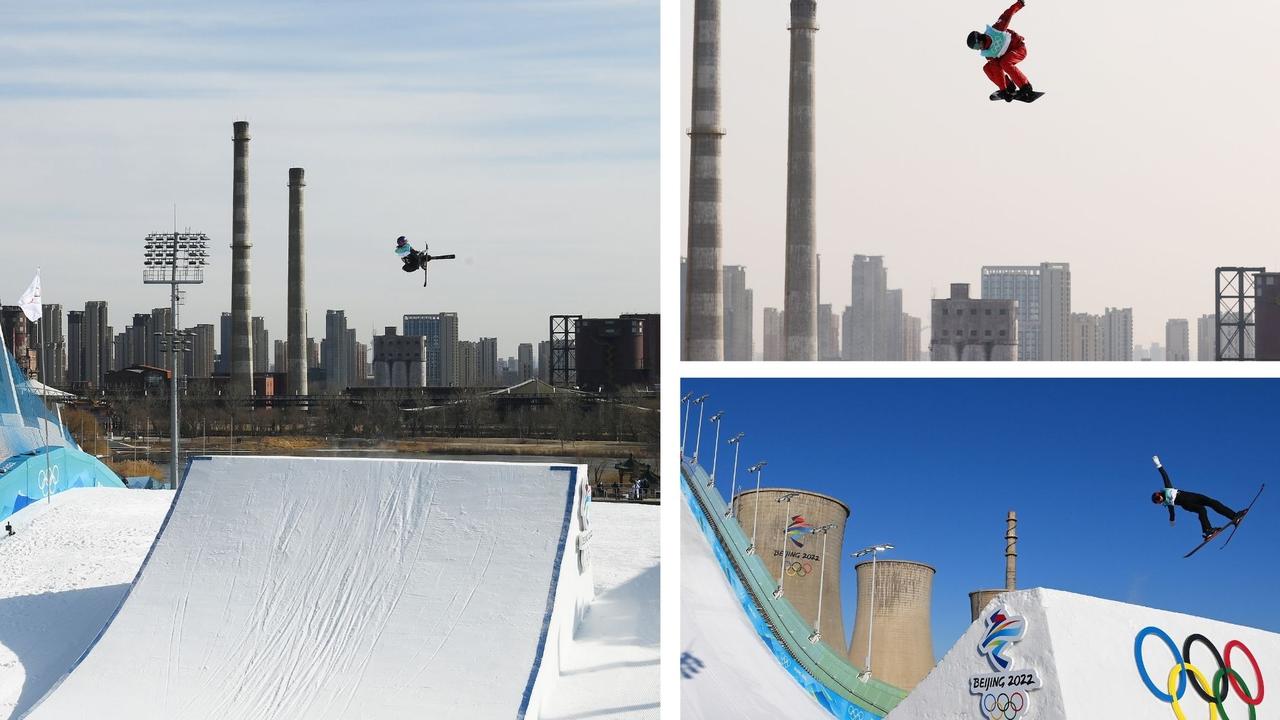

The Olympics has thrown up several golden — and not so golden — moments at the end of the first week, but one image truly went viral.

On Tuesday, American-born Chinese skiing wunderkind Eileen Gu, who defected to the host nation on the eve of the Games, won her first gold medal in the freeski Big Air competition.

But while it was brilliant result for the woman who has become the face of the Olympics after defecting from the US to China, the backdrop of the event caught the eye of fans.

In the background of the ramp which was build in the middle of an industrial area, were giant smoke stacks, that saw some declare it a “nuclear power plant wasteland”.

Losers reacting to a photo of a temporary ramp by a repurposed power plant: “Dystopic!â€

— justin caffier (@JustinCaffier) February 8, 2022

Me and other cool folk: “Dis pic dope!†pic.twitter.com/2e0bzKuJUM

Exuberant ski jumps executed on a snowless terrain in the shadow of a nuclear power plant bum me out.

— Bradley Whitford (@BradleyWhitford) February 8, 2022

It is not a nuclear power plant, rather cooling towers for a decommissioned steel mill.

Regardless of what it actually is, the nuclear power plant idea spread quickly, some appeared to hate the visual, while others thought it looked awesome as a backdrop.

On Thursday, the Beijing Organising Committee hit back at the claims through spokeperson Zhao Weidong.

“It’s totally an absurd speculation to relate the venue to an abandoned nuclear facility of any kind,” Zhao said during a news briefing on Thursday.

“It was actually built on the former site of the Shougang steel factory, which has been renovated and repurposed into a public park for hosting sports and cultural events as well as conventions.

“It’s an example of sustainability and an impressive practice of using the Olympic Games’ impact for urban development.”

And it’s set to stick around as a permanent fixture of the park.

Swedish men’s bronze medallist Henrik Harlaut praised the location.

“It’s a perfect, bigger venue. It’s so well-built and the first permanent Big Air venue ever,” he said.

“We’ve done a lot of city Big Air where it’s on scaffolding towers, where it’s always kind of sketchy with a narrow in-run and short landing area. So to be here where it’s a super wide in-run and there’s even space on the side of the jump so you can ride out without being scared of it … it’s definitely very nice for us.”

History of Big Air Shougang

The 60-metre-high “Big Air” jumping platform built on the grounds of a century-old decommissioned steel mill has become an international social media sensation, blasted by critics as “dystopian” and lauded by others as an innovative example of urban renewal.

Industrial origins Big Air Shougang was built on the grounds of an old steelworks that once employed more than 200,000 workers.

The plant, constructed in 1919 and operated by the now state-owned steel giant Shougang Group, had the capacity to make 10 million tonnes of steel per year at its peak, according to state news agency Xinhua.

The huge Capital Iron and Steel Works was a showcase for Communist leader Mao Zedong’s attempts to rapidly modernise the then poverty-stricken nation.

But with its huge output came massive pollution — the factory’s smokestacks spewed up to 9,000 tonnes of pollutants into the air each year, filling the surrounding Shijingshan district with thick smog.

“Local residents dared not to go outdoors to enjoy the cool during sweltering summer nights, they dared not eat meals outdoors and dared not dry clothes outdoors — in just one night, white clothes could be turned black,” retired steelworker Lu Zengzhi told Xinhua in 2011.

In an effort to clean up the capital’s air ahead of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, the Chinese government in 2005 ordered the factory to begin moving production away from the city.

The plant shipped its last batch of steel wires in December 2010.

Influencer magnet The defunct steel mill has turned into a trendy destination akin to London’s Battersea Power Station in recent years, home to bars, offices, museums and a Shangri-La Hotel featuring exposed concrete and steel.

Influencers now flock to the area, drawn by its grungy aesthetics, with users of the Instagram-like Chinese app Xiaohongshu sharing tips on how to get the most artistic shots of its rusting machinery.

The region has been partly inspired by the success of “798”, a former Beijing factory that is now a thriving state-backed art zone.

The Big Air platform was unveiled in 2019, when it became the world’s first permanent venue for freeski big air competitions.

City authorities have also built an ice hockey arena in the former industrial park.

Big Air Shougang’s international debut at the Games turned it into a polarising internet sensation.

Screenshots of Olympics events at the venue as well as an aerial view showing the jumping platform surrounded by what looked like a grey industrial wasteland were retweeted thousands of times, with one Twitter user calling the scene a “hellscape.”

Republican politician Ted Cruz jumped on the bandwagon Tuesday, commenting that “China couldn’t make the Olympics any more dystopian if they tried”.

Others turned the photo of the jumping platform into a meme, photoshopping it into an iconic photo of American fast food and gas station signs in Breezewood, Pennsylvania, and comparing it to the fictional Springfield Nuclear Power Plant in the Simpsons TV show.

But the venue has also been praised as a unique example of repurposing old industrial facilities, with the park winning an award from the Netherlands-based International Society of City and Regional Planners in 2018.

The future of the Winter Olympics

While there has been plenty of criticism of the venues in Beijing which have resulted in injuries, it appears like this could be the future of the games.

The impact of climate change has been one of the big talking points of the Olympics and while the temperatures have been in the minus’ for most of the event the area chosen to host the Games doesn’t get much snow and relying on artificial snow.

NASA even released pictures above the slopes, showing brown mountains with wisps of white where the events are being held.

While the vision from the Games, can’t possibly show how difficult it is for competitors as the images make it look like it’s a winter Wonderland.

Only around 10 per cent of the snow used for competitions at Zhangjiakou, hosting the majority of ski and snowboarding events, is natural and the amount of artificial snow used at Yanqing, hosting alpine skiing and sliding events, is close to 100 per cent.

However, before the event, athletes were far from impressed by what they saw.

Two-time defending snowboard slopestyle champion Jamie Anderson said she was “scared of riding on the artificial snow because it was like “bulletproof ice”.

Several events have been rocked by serious injuries, including American Nina O’Brien, who fell on the final gate of her giant slalom run and ended up with a compound fracture of her tibia and fibula. Other competitors were much luckier as they just crashed out of their events.

But the artificial snow has been slammed for causing several injuries in the events so far.

“I think we might see more injuries than we normally do because of the course conditions, and potentially, some of those injuries may be even more serious than we would otherwise see because of the amount of speed that the athlete has when they take the fall,” US orthopaedic surgeon Dr Mia Hagen told news site King 5.

“Nordic skiing events, where the skis are set up a little bit differently, that can pose a real danger for the athletes, particularly when they take turns on that icier snow.”

It was estimated the Games would churn through 49 million gallons of chemically-treated water frozen through snow machines, which has environmental consequences of its own.