Trainer David Hayes continues to build his hugely successful racing empire

MOST things in David Hayes’ life have been on a dizzy scale. To the average punter, it’s a case of add a zero, then multiply by 10.

MOST things in David HayesÂ’ life have been on a dizzy scale. To the average punter, itÂ’s a case of add a zero, then multiply by 10.

Winners? Just a few — 2800 and counting. A handful of Group 1s — 78.

Horses? There are 135 on the books and 100 resting in lush paddocks.

In Hayes’ world of very big numbers, the 235 horses is a reduction. In his heyday, just after he returned from Hong Kong in 2005 in a spectacular winning splurge, Hayes had 550 racehorses on his bulging books.

Property? Just a neat house(s) and land parcel of 1200 acres 485ha in a postcard valley near Euroa, complete with extraordinary trappings and gadgets, including five rented homes in the nearby town for his army of staff and a horse pool so hi-tech you can drink from it.

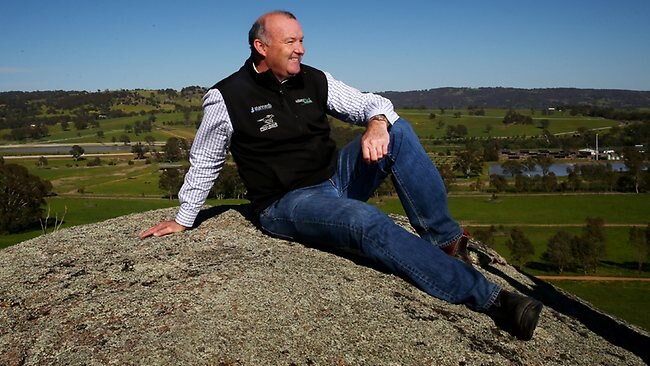

Cost? Lindsay Park Euroa, the second coming of racing’s most famous plot of land, has stripped $20 million from Hayes’ bank account. Standing atop a rocky vantage point, Hayes surveys his “modest’’ garden and talks of new projects; new training tracks, a jetty jutting from a dam filled with perch and redfin and a deer and kangaroo sanctuary, for the benefit of visiting owners.

Debt? Try $8.5 million as a 30-year-old back in the mid-1990s, when the legendary C.S. Hayes called his two sons to a roundtable meeting in the bluestone homestead at the first Lindsay Park, in the Barossa Valley.

Predicting his kids might start dashinghead in different directions, C.S. demanded one son buy out the other’s stake in the farm. David, the optimist, bought out Peter, the pessimist. Just a small exchange between siblings.

Playing to scale, after handing over a fortune to his older brother, Hayes took off to Hong Kong and didn’t muck around, repaying $8.5 million in three wildly successful years. Seven years later, Hayes returned from Hong Kong “very solid financially”.

Then, A few years later, this grand-scale life swung spectacularly the other way. Hayes had a debt so severe the banks were banging on his door as he juggled his finances, trained his horses and “shut the master ship down and built another”.

Hayes wasn’t accustomed to living lean, although he and wife Pru have always been frugal with their four kids, whom Hayes hopes will one-day inherit the kingdom.

If none is keen, Hayes has a $20 million horse property and no one to hand it to. “They’d have to be passionate. You wouldn’t do it just for the sake of it. Lucky, the three boys are all passionate,’’ he said.

Hayes, suddenly, couldn’t buy the yearlings he liked because he didn’t have the money. Most frustrating, the money was almost there but out of reach.

Even in the context of Hayes’ life on the big stage, there was something monumental about a dinner in Adelaide last Monday.

For three years Hayes had been trying to flog the last of four parcels of the old Lindsay Park, the famous Barossa Valley property bought by his legendary father Colin in 1965.

He sold one parcel to his nephew Sam, the son of Peter, who died tragically in a plane crash in 2001. He later sold more to his ex-foreman Tony McEvoy, and McEvoy’s wealthy mate, Wayne Mitchell.

The McEvoy deal was struck on a simple handshake.

The last parcel, which Hayes reckoned was worth $10 million and included the family homestead, was “sold’’ three times in three years but the deals kept falling over.

“With McEvoy it was a handshake and here’s the keys. The others were more complicated,’’ Hayes said.

“It was frustrating.’’

For three years, as this last parcel remained unsold, Hayes was asset-rich and cash-strapped. His kingdom was in transition and the cash freeze meant projects at Euroa didn’t exactly stall, but proceeded under the weight of bank debt.

For 18 months,a year and a half, with one property being built and another not yet sold, the horses weren’t compromised but they weren’t winning.

For a 50-year-old trainer who hadn’t been outside the top three — here or in Hong Kong — since he was 26, having runner-less Saturdays and near runner-less spring carnivals was hard to cop.

“It hit me one day when I didn’t have a runner on Caulfield Guineas day and watched from home. That was hard,’’ he said.

The debt was preying on his mind, although the great optimist always believed his white knight would come. He did, in the form of a Hong Kong-based Chinaman man called Mr Tan.

A week ago Hayes escorted the billionaire around the old South Australian property.

“It was a bit sad. The place hadn’t been a working property for three years and you could see the decline,’’ he said.

Mr Tan liked what he saw and had visions of a multi-million-dollar makeover; a golf course, a polo field and some thoroughbreds.

Over dinner in Adelaide, Hayes handed Mr Tan the keys to the old kingdom and Mr Tan handed over a cheque for $10 million.

“Dad had a master key attached to a Swiss Army knife on a gold chain. It opened every door at Lindsay Park. I handed it to Mr Tan as what you might call a ceremonial gesture,’’ Hayes said.

The Hayes story has been told many times; the phenomenal success of a father and two sons, the dramatic transition from one farm to another, the tribulations, the optimism, are well documented.

Mr Tan’s cheque has been banked and the second Lindsay Park is complete, bar a few deer and some redfin.

The resurgence is on.

Hayes has ridden out the toughest three years of his successful, fortunate life. He always held his nerve.

“I’d probably have given up if I didn’t think there was a reason (for the poor result), but there was. We were in transition,’’ he said.

From nowhere, Hayes almost chased down Peter Moody in last season’s premiership.

He has lots of horses, but is no longer the “biggest’’ trainer around. He has Bass Strait in the Toorak Handicap today, Gregers in next Wednesday’s Thousand Guineas and star import Jet Away in next Saturday’s Caulfield Cup.

It’s not the halcyon days, but it’s creeping close.

Hayes once dreamt of a small, boutique team but quickly realised he was a numbers man, unaccustomed to being a bit player at big carnivals.

“I still don’t think I’ve totally turned things around. I hope to have a Group 1 winner or two over the spring carnival, which is a big change from having next to nothing a year or two ago,’’ he said.

“I’m half the size I was a few years ago, but I’ve reached a happy medium. I think we’re still big enough to make an impact.’’