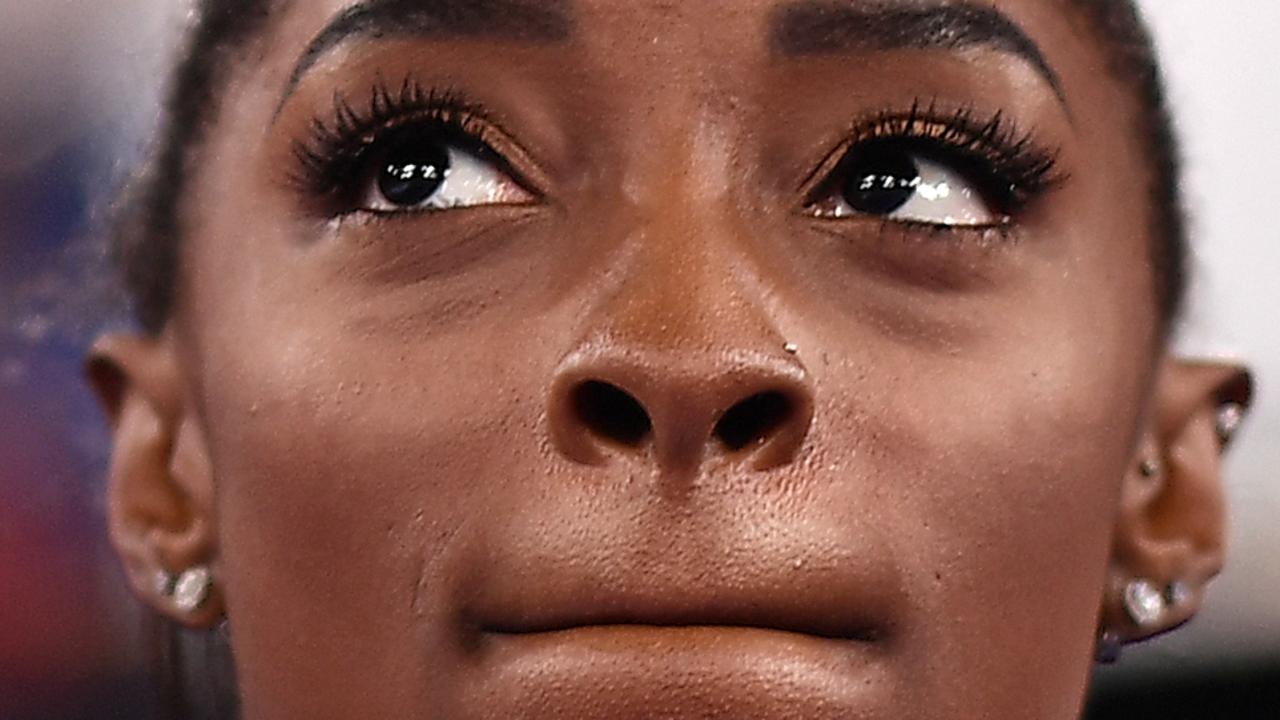

‘Selfish sociopath’: Simone Biles cops vile abuse from her own country

Gymnast Simone Biles’ critics have called her “weak”, a “quitter” and far worse. But her life is a story of strength in the face of trauma.

Less than 24 hours before competing in the 2018 world championships in Doha, Simone Biles visited the emergency room to investigate pains in her stomach.

The doctors found a kidney stone.

Biles decided not to have it removed. She left hospital in the small hours of the morning, still in agony, yet still determined to compete.

“The kidney stone can wait,” she said.

Gymnastics’ doping rules barred her from taking proper pain medication.

“The pain was coming in waves. I was walking around and then I’d be literally crawling on the floor because it hurt so bad,” she later revealed.

No matter. Those world championships proceeded towards the same inexorable conclusion as every other major competition Biles had contested since 2013: she landed moves her peers weren’t even capable of attempting, won four gold medals, and led the American team to the largest margin of victory ever recorded under the sport’s modern scoring system.

That same year, Biles won the US national championship with broken toes in both of her feet.

This is the woman critics are now branding “weak” and “a quitter” after her withdrawal from the Tokyo Olympics.

“I have to focus on my mental health and not jeopardise my health and wellbeing,” Biles said after the United States won silver without her on Tuesday.

“It just sucks when you’re fighting with your own head.”

RELATED: ‘What a joke’: Piers Morgan slams Simone Biles

The elegance of gymnastics can obscure just how punishing it is. Elite gymnasts like Biles wear down their bodies in pursuit of perfection, often causing self-inflicted, lifelong health problems.

“Pain is just something I live with. And that is pretty odd for my age, right? It feels weird if I’m not in pain,” Biles once said. She was 22 at the time.

“I’ve been quite fortunate with injuries, but there’s been some stuff. There’s been a calf I have partially torn two or three times. I broke a rib in 2016. And oh yeah, it turned out my toe was shattered in five pieces after the last Olympics without me knowing.

“That was weird. I had it for ages and used to tell people it was going to fall off. One day I had it X-rayed and they were asking how long it had been bad. I’d had it about two years.

“If you are jumping up in the air all the time, sometimes gravity says no.”

Biles has been defying gravity, and her body, since the age of six.

She is, indisputably, the greatest gymnast of all time, with 27 gold medals in her cabinet, five world championship titles and four moves named after her. It’s been eight years since she lost an all-around competition.

Federer has Nadal and Djokovic. James has Jordan. Woods has Nicklaus. Williams has Court. Biles has no equal, no rival, no cloud of doubt over her status in history.

In a sport where the slightest mistake can cause a catastrophic injury, no one else has ever performed routines as dangerous as hers, with so many death-defying twists and somersaults stuffed into every available millisecond.

You can’t reach that level of skill on raw talent alone. It costs something.

“Oh, this body. It starts when I wake up. I can tell you almost straight away if it is cold or not because my bones will shake,” said Biles.

“I joke to my friends a lot that I am going to be in a wheelchair at 30. My body feels like it is maybe in its thirties or forties. Maybe older. Inside it is screaming and yelling at me.”

RELATED: Simone Biles’ revealing off-camera acts

Simone Biles' double-double dismount is now known as the "Biles"

— Bleacher Report (@BleacherReport) October 7, 2019

Only 22 years old and already has FOUR total moves named after her ðŸ‘

(via @NBCOlympics) pic.twitter.com/JVPP3DmDcm

Imagine doing that to your body, persevering through the pain and executing impossible moves to perfection, again and again. And always with the world watching expectantly.

Then add the incalculable emotional toll of surviving sexual abuse.

Biles is among more than 150 women who say they were abused as girls by Larry Nassar, the former US team doctor who is now serving a life sentence in prison.

She has used her profile as American gymnastics’ biggest star to push for reform in the broken system that protected Nassar, and other abusers, for decades. It’s one reason she is still competing now at the age of 24, old for a gymnast.

“If there weren’t a remaining survivor in the sport, they would’ve just brushed it to the side,” she explained in April.

Biles has previously spoken about the extreme mental trauma she suffered, which prompted her to seek therapy and take anxiety medication.

“I remember telling my mum and my agent that I slept all the time, and it’s basically because sleeping was better than offing myself,” she said in her docu-series, Simone vs Herself.

“I was super depressed, and I didn’t want to leave my room and I didn’t want to go anywhere, and I kind of just shut everybody out.”

That is the sort of pressure Biles has dealt with, faultlessly, since she was in her teens.

And yet.

“Simone Biles is a quitter,” Amber Athey declared in The Spectator yesterday.

“Biles may be the most skilled gymnast ever, but a true champion is someone who perseveres even when the competition gets tough.”

Charlie Kirk, a right-wing talking head, called Biles “immature”, a “selfish sociopath” and a “shame to this country”.

“We are raising a generation of weak people like Simone Biles,” said Kirk, whose own record of strength and perseverance is limited to having dropped out of college.

“Simone Biles just showed the rest of the nation that when things get tough, you shatter into a million pieces.”

Charlie Kirk calls Simone Biles a "selfish sociopath" and a "shame to the country"

— Jason Campbell (@JasonSCampbell) July 27, 2021

"We are raising a generation of weak people like Simone Biles" pic.twitter.com/yDLtblAS35

Writing for The Federalist, John Davidson also took the view that Biles’ withdrawal was a symptom of some broader, society-wide weakness.

“We as a society have begun conflating mental health and mental toughness, or grit. Public figures are often rewarded for taking care of their ‘mental health’, even in the absence of any kind of mental illness,” he said.

“Biles doesn’t suffer from a specific mental illness, at least not that we know of or that’s ever manifested itself before.

“What she experienced wasn’t that, it was something more common among professional athletes: she got psyched out. She wasn’t mentally tough when she needed to be.

“Instead of being ashamed of that, or apologising to her teammates and her countrymen, Biles seemed to revel in taking care of her ‘mental health’, whatever that means.”

Whatever that means. Seriously.

One more example. Piers Morgan, ever keen to slam an athlete for prioritising her mental health, said Biles “just gave up at the first hurdle” in Tokyo.

“The Olympics are the pinnacle of sport, the ultimate test of any athlete. They’re supposed to be very hard and very tough, physically, mentally and any other way you care to name,” the British broadcaster wrote.

“I preferred the old Simone that would do whatever it took to win.”

He went on to critique the people lauding her choice, saying they were celebrating “losing, failure and quitting as greater achievements than winning, success and resilience”.

“Sorry if it offends all the howling Twitter snowflake virtue signallers, but I don’t think it’s remotely courageous, heroic or inspiring to quit.”

Here’s an idea. Maybe, when a proven champion with a long record of successfully handling immense pressure tells us she is struggling with her mental health, our first instinct should be to believe her, not berate her.

We should remember that athletes are human beings, not emotionless automatons.

As Biles’ former teammate Aly Raisman said yesterday: “She knows her body and mind better than anyone else.” We can certainly guess at what, precisely, she’s going through, but only she knows.

Here’s what the rest of us can glean for sure. Biles did not, as Morgan asserted, quit at the “first hurdle” on Tuesday. That ignores the entire context of her decision, presupposing that she was completely fine until she stuffed up one attempt at the vault. It ignores a lifetime of hurdles few could surmount – pain and trauma, physical and mental, on a level most of us have never experienced.

You don’t have to praise her withdrawal, which did after all blindside her teammates in the middle of a competition. But how hard is it to show a shred of empathy?

“We’re humans, right? We’re human beings. Nobody is perfect,” Olympic great Michael Phelps, now a rather eloquent correspondent for NBC, said yesterday.

“It is OK to not be OK. It’s OK to go through ups and downs and emotional roller coasters.”

Andrea Orris, a former gymnast who now coaches, is nowhere near as famous as Phelps, but it’s worth reading her words too.

“It makes me so frustrated to see comments about Simone not being mentally tough enough or quitting on her team,” Orris wrote.

“We are talking about the same girl who was molested by her team doctor throughout her entire childhood and teen years. Won the world all-around championship title while passing a kidney stone. Put her body through an extra year of training through the pandemic. Added so much difficulty to her routines that the judges literally do not know how to properly rate her skills because they’re so ahead of her time.

“Some people can still honestly say that, ‘Simone Biles is soft. She is a quitter.’ That girl has endured more trauma by the age of 24 than most people will ever go through in a lifetime.

“After her track record of all she’s pushed through, the fact that she took herself out of the competition on her own merit means that whatever she is dealing with internally has to be insurmountable and should be taken seriously.”

Simone Biles is not weak. She’s human. Given we’re talking about a sport with a long history of dehumanising and abusing its stars for the sake of our entertainment, maybe it’s time for us to acknowledge that their health is more important than any gold medal.