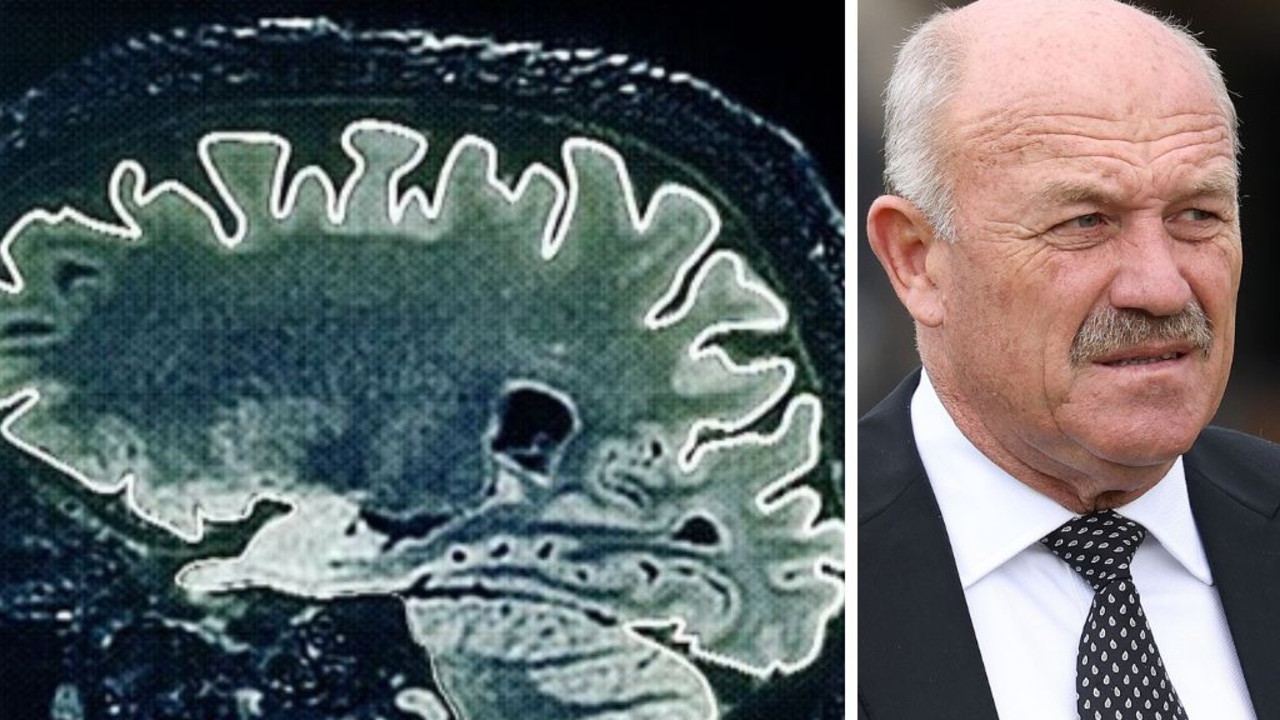

Wally Lewis, rugby league legend, reveals he’s been diagnosed with neurodegenerative condition

Rugby league legend Wally Lewis revealed he’s battling a devastating condition in a frank interview with 60 Minutes.

Rugby league legend Wally Lewis is battling a devastating neurodegenerative condition, he revealed in an interview with 60 Minutes on Sunday night.

Lewis, a State of Origin hero for Queensland and former captain of Australia, has been diagnosed with “probable CTE”, which stands for chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

The brain condition, a form of dementia, is triggered by repeated mild traumatic brain injuries, such as those one might suffer from contact to the head in a footy game.

It was first discovered in boxers about a century ago, and has since been studied in connection with contact sports like American football, rugby, rugby league and AFL.

Sitting down with 60 Minutes, Lewis revealed he had been suffering from severe short term memory loss. Illustrating the struggle, he said he was unable to recall exactly what his doctors had told him about the condition, and had to be reminded of its name.

“What’s the diagnosis?” interviewer Tom Steinfort asked him.

“There’s the big one. I can’t even remember the name of what it’s called,” Lewis responded.

“Probable CTE,” his partner, Lynda Adams, offered from off screen.

The condition can affect memory, behaviour and basic cognitive skills, and grows worse over time. It is particularly prevalent in retired sportsmen.

“In one of my first meetings with the doctor, when she asked to repeat simple things – I think she gave me five things, and it might have been something like bus, dog, truck, camera, chair. And she said, ‘Remember those.’ And went over them two or three times,” Lewis recalled.

“A minute later she said, ‘What are the things I asked you to remember?’ And I got two of them. And then sometime later, after that, she said, ‘Do you remember what they were?’ And I think I said ‘bus’.

“Pride’s a wonderful thing, but there wasn’t much of it around then.”

The test he described is similar to the one former US president Donald Trump once bragged about passing, and is designed to assess cognitive function.

Steinfort pointed out that, while Lewis had a reputation for extreme toughness on the field, often it can be just as tough to acknowledge one’s frailties.

“For a lot of the sport guys, I think a lot of us take on this belief that we’ve got to prove how tough we are,” Lewis replied.

“How rugged. And if we put our hands up and seek sympathy, then we're going to be seen as the real cowards of the game.

“But we’ve got to take it on and admit that the problems are there.”

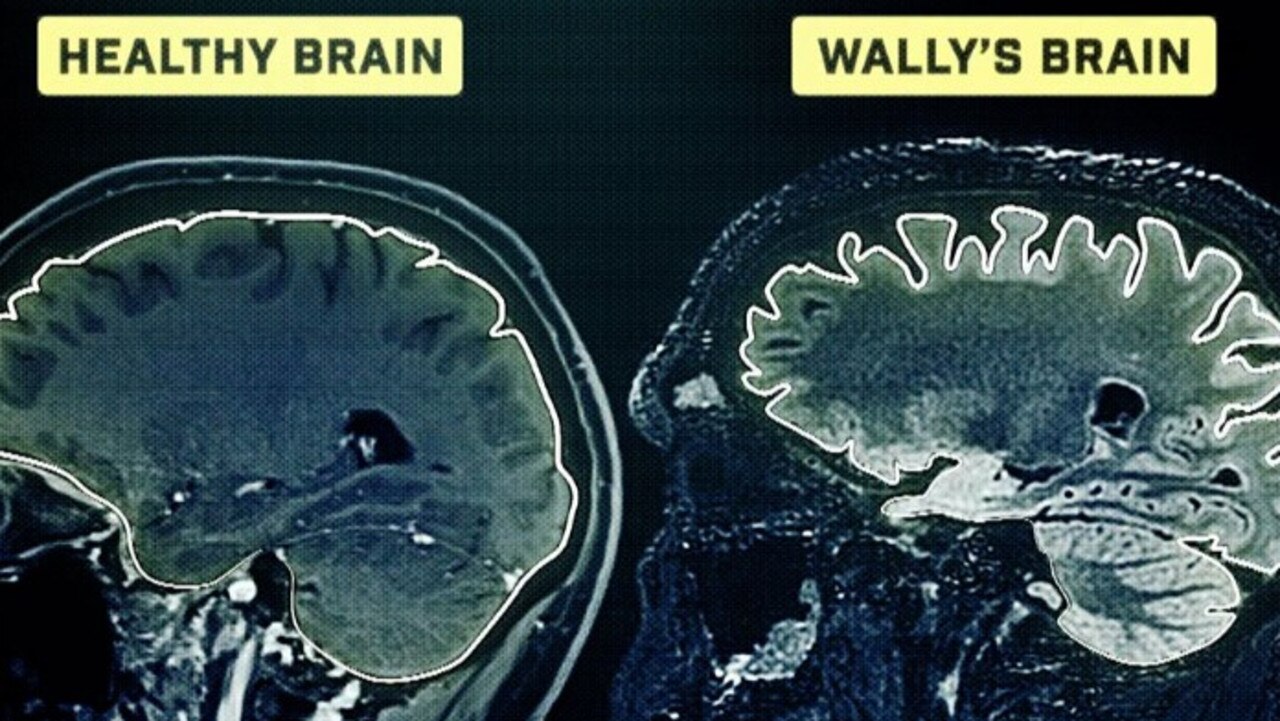

While CTE can currently only be diagnosed with complete certainty after the patient’s death, via an autopsy of the brain, Lewis’s neurologist Rowena Mobbs told the program she was “90 per cent” certain of his diagnosis, citing multiple tests and the deterioration of his memory.

One such test, captured by the comparison below, show atypical “valleys” in his brain, which indicate shrinkage and the loss of brain cells.

“It’s devastating,” said Dr Mobbs, who said she was encountering a growing number of former sportspeople with the condition.

“It’s hard to see the players go through it. They’re people I’ve admired and loved growing up, so the last thing I want to do is diagnose them with dementia.”

Lewis previously underwent brain surgery after an epilepsy diagnosis. Years later, instances of short term memory loss were the danger sign that grabbed both his and Adams’ attention.

“I remember Wally picked me up, he talked to me about something, and we were driving along, and about three minutes later he said – it was as if he’d never told me – told me the same story,” said Ms Adams, remembering one such incident.

“I said, ‘OK,’ and then about three or five minutes later, he told me the same story.”

Lewis stressed that he didn’t regret his decorated career in the sport.

“Would I change a thing? No, I wouldn’t,” he said.

“I loved the game that I played. I felt privileged to have played it, and to have been given that chance. When you go out there and you’re wearing the representative jerseys, particularly the one for Australia, you feel ten feet tall and bulletproof.

“Well, you might think you are. But you’re not.”

He said players were seeking not “sympathy”, but “support”. As such, he has decided to donate his brain for research upon his death.

In a statement to 60 Minutes, the NRL said it had “some of the most comprehensive head injury policies and procedures” in the sporting world, and argued that its management of head injuries and concussions had “progressed significantly over recent decades”.