Still no sign of missing African Commonwealth Games athletes

FOR some athletes, the chance to escape a worn-torn, poor or oppressive home country proved more valuable than any gold medal.

IT WASN’T a Games record, but as a statistic, it will have ramifications as long lasting as a medal tally.

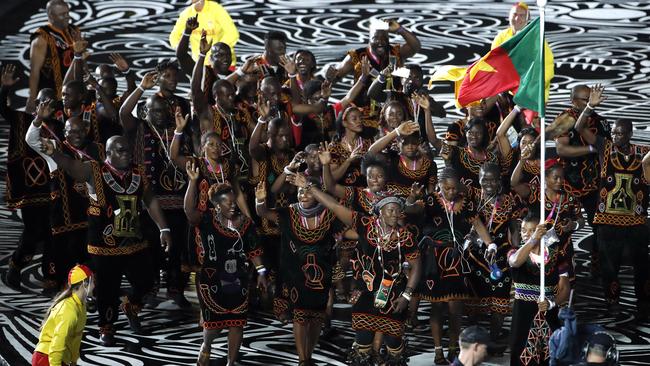

It’s the 13 athletes at the Gold Coast’s Commonwealth Games who upped stumps and seemingly deserted their sporting dreams in favour of life in Australia.

The athletes from Cameroon, Uganda, Rwanda and Sierra Leone aren’t in breach of their visas — yet. They expire at midnight on May 15.

And they aren’t the only guests who haven’t made the return trip home yet. A handful of officials also did a disappearing act: like Rwanda’s weightlifting coach, who excused himself to go to the toilet before his team competed — and never came back.

Ahead of the closing ceremony. the teams remained hopeful the missing athletes would surface, and Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton was talking tough.

Ugandan Commonwealth Games flag-bearer Peace Proscovia said she hoped two of the nation’s athletes would return to the village before Sunday’s closing ceremony, believing the missing pair could be visiting friends or relatives in southeast Queensland.

By Tuesday, the Cameroon team chief — having heard nothing form his eight missing athletes, one-third of the Cameroon team — had given up hope.

The eight, mainly boxers and weightlifters, had walked out in a series of late-night flits, one even failing to front for his event.

The Games were over and chef de mission Victor Agbor Nso, clearly sick of the media scrutiny over the mass walkout, said the matter was now in the hands of police and the Australian Government.

When his eight athletes disappeared, he told the BBC “the authorities are very disappointed with the deserters — some did not even compete”.

On Tuesday, he told the ABC he wanted to make sure the remaining team members had all left Australia before he flew out of the country, and seemed to be looking forward to getting some peace on the flight: “I don’t want to talk about this any more, I am concentrating on returning home.”

Meanwhile, the clock counts down to May 15.

After that, Mr Dutton warns, they face deportation for breaching their visa.

“If they don’t want to be held in detention or locked up at the local watch house, they’d better jump on a plane before the 15th (of May),” he said.

During the Games, Ian Natherson, a migration consultant based on the Gold Coast, took more than 40 calls — mostly from African team members — looking for legal ways to stay in Australia after the Games.

“Just walking down the street [here] the freedom you have — you cannot do that in a lot of African countries,” he told the ABC.

“I come from South Africa myself, where I would not walk the streets after dark.

“I am sure a lot of them did do that here and just thoroughly enjoyed the freedom.”

TWO WHO MADE IT

For some athletes, the chance to escape a war-torn, impoverished or oppressive home country, is more valuable than any gold medal.

Mr Dutton’s threats aside, the issue of absconding African athletes from sporting events is only going to get worse, and article in Quartz Africa predicts.

In 2006, at Melbourne’s Commonwealth Games, more than 40 athletes or officials either overstayed, or sought asylum.

Cameroon weightlifters Francois Etoundi and Simplice Ribouem both received refugee status — and were in this year’s Australian team.

Ribouem won bronze in Melbourne before he took his chance to never return to his violent home country and seek asylum.

“There’s shooting and people get killed, we don’t have that here in Australia, you can walk wherever you want to and you are feeling free. Free like a bird, not even the bird is free like you”, Ribouem told SBS ahead of this year’s Games.

“There they’ve got political issues, all the state fighting affect the population, affect a lot of the population.”

Of those first nights back in 2006, he decided to try for asylum instead of returning to poverty in Cameroon where his parents were.

“[The] first couple of nights were really hard. I slept outside the village in a park in Brunswick on a bench. It was freezing, I had no blanket,” he said.

After he failed to return to Cameroon, the country’s government persecuted his family. His father had died but he feared for his mother’s safety, and moved her to live in a rural area to protect her.

Ribouem has won gold and silver medals for Australia in Delhi 2010 and Glasgow in 2016, but had to pull out his event at the Gold Coast after aggravating a knee injury.

Etoundi fought through the agony of tearing a bicep to win bronze in his division on the Gold Coast — revving up the crowd along the way with backflip celebrations.

WHY THEY DO IT

At the 2012 London Olympics, 21 members of African teams went missing or claimed asylum.

Why do they do it? Because they are searching for a better, more fruitful life, or escaping political repression at home.

While sporting prowess and success may make their paths easier in their home countries, the reality is it’s still far from a lucrative pursuit at home.

High profile or uber-talented African athletes might have the option of switching nationalities to relocate, train and compete, but for other athletes, a berth in a national team may be their single chance to escape their home life as they know it.

In fact, team selection might be their only opportunity to leave a country safely and with a valid visa.

WHAT’S NEXT

The missing team members have until May 15 to apply find a way to legitimately stay.

Applying for asylum depends on being able to convince authorities there’s a threat to their lives if they return to their home country.

A special skills visa might allow them to live in Australia and compete as professional athletes.

But for some, the risk of emerging from hiding and being sent home might be judged too great.

It’s tipped they will try to stay under the radar, with no legal documents, living as best they can, with menial jobs. And always the threat of being discovered.

Originally published as Still no sign of missing African Commonwealth Games athletes