Mike Tyson got $30m for infamous ear-biting fight – then blew $1.15m in a day

At the height of his fame in the 1990s, handing Mike Tyson a $30 million cheque was a recipe for disaster.

The day before Mike Tyson’s infamous rematch against Evander Holyfield in Las Vegas in June 1997, the heavyweight boxer went to collect his pay check at the office of his promoter, Don King, at the MGM Grand.

A grinning King pulled out a pen and wrote a check, which he held up for Tyson to see.

The sum? $30 million — and all before the boxer had even fought.

“I’ll see you tomorrow night,” King told Tyson. “Now, just don’t get into any trouble tonight, my brother. Just keep it calm.”

In “Talking To GOATs — The Moments You Remember and the Stories You Never Heard” (HarperCollins), out now, sportscaster Jim Gray details this moment and other astonishing eyewitness accounts of Tyson, his friend of more than 35 years.

The moment Tyson left King’s office, the boxer jumped into his new $350,000 Lamborghini, reversed it straight into a parking barrier, and dented the fender, Gray writes.

Convinced the car was cursed and screaming that he didn’t need any bad luck before his big fight, Tyson leapt out of the car and threw the keys at a nearby security guard, telling him to keep it.

“Take this f***ing car,” Tyson screeched. “Get this f***ing car away from me!”

Perplexed, the security guard turned to King. But the promoter simply shrugged.

“Ay brother, my man is giving you this car,” King replied. “Take it, have a good time.”

And with that, the security guard sped off in his new sports car.

More than an hour later, Gray was dining with King at The Palm restaurant when a messenger arrived and said there was an emergency.

Leaving the restaurant, King found Tyson exiting Caesar’s Palace where, according to reports, the boxer had just spent $800,000 at the Versace store.

“I remember he bought purple shoes and yellow and orange scarfs,” recalls Gray in the book. “The second he took that stuff out of the store, it had no value. He didn’t care. He ordered King to take care of it.”

Between his shopping spree and giving up the sports car, Tyson had burned through $1.15 million in less than 90 minutes.

“Give me back the check,” demanded King in a last-ditch attempt to save Tyson from himself. Reluctantly, Tyson complied.

TV journalist Gray first met Mike Tyson at Matteo’s restaurant in Los Angeles in the mid-1980s when the boxer was still a teenager. Gray bumped into the boxer on the way to the rest room, and Tyson recognised him from TV, sat down at his table and forged their friendship.

But, as Gray writes, Tyson indulged in having a good time and everything that went with it, “whether that was drinking or women or more women, cars, clothes, jewellery, and watches. You name it. He wasn’t living a life of regret.

“Tyson has lived his life on his terms, on a high wire without any net.”

No party was too lavish for Tyson. After he beat Tony Tucker at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas in 1987 to become the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world, the fighter entered his celebration party wearing a blue cape, holding a sceptre and sporting an ornate crown festooned with real gems. Then he settled down to feast on a whole roasted pig weighing down the buffet table.

“It felt like something out of the 1700s,” writes Gray.

It’s easy to see how Tyson eventually spiralled out of control.

Raised in Brownsville, Brooklyn, he endured a torrid childhood, characterised by what he called “poverty and chaos”.

He never met his biological father, and his stepfather also abandoned the family. The young Tyson ran with drug dealers and convicts and was arrested 38 times before he was 13 years old, ending up in a juvenile detention centre.

After his mother died when he was 16, he was officially adopted by his first boxing trainer, Cus D’Amato, who became Tyson’s legal guardian.

“It was boxing that saved him — and nearly destroyed him,” writes Gray.

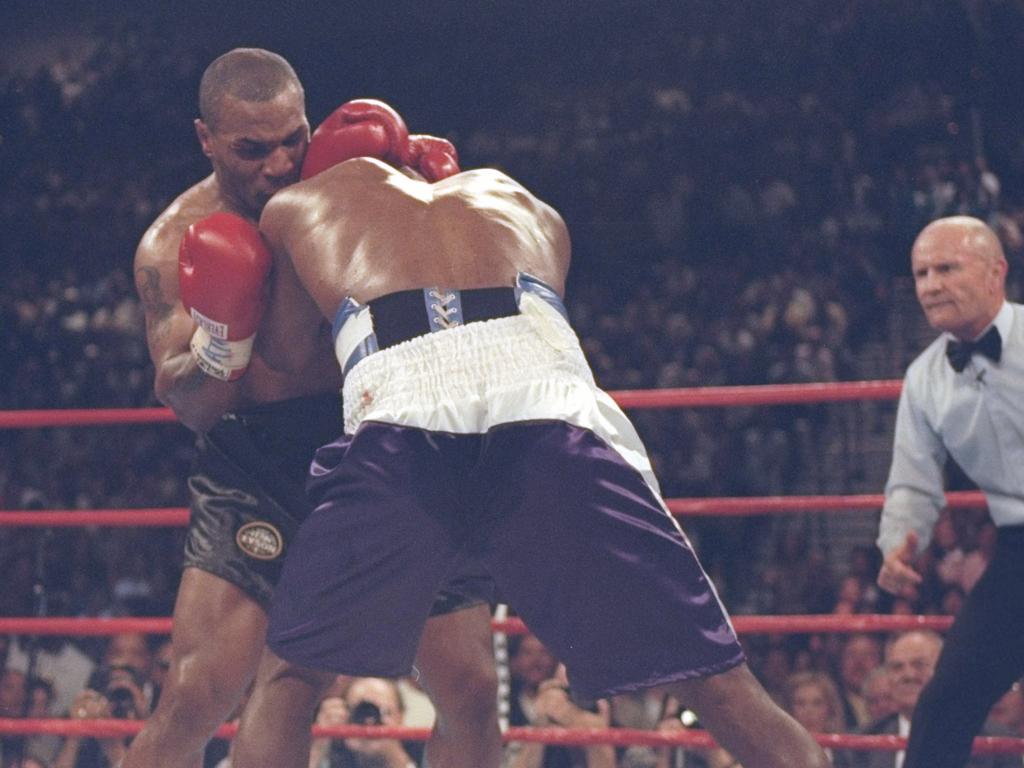

At times, the boxer was his own worst enemy. During the rematch with Holyfield at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, billed as “The Sound and the Fury,” Tyson had become agitated by his opponent’s repeated headbutts, one of which left him with a large cut over his right eye. In retaliation, Tyson famously bit Holyfield’s right ear and removed a lump of his lobe in the process.

As a result, Tyson was permanently suspended from boxing and his license to fight was revoked, a decision that was overturned a year later.

Gray was also a witness when Tyson held a man by his ankles outside a third-floor hotel window in an argument over money (“Bitch, can you fly,” shouted Tyson, as his victim dangled).

And he was on the other end of the microphone when Tyson, high on success in 2000, told Gray that he intended to rip out the heart of rival boxer Lennox Lewis and then eat his children, too.

Tyson even threatened to kill Gray and promoter Don King during an interview.

“I said, ‘Why?’ He said that King had stolen money from him, and I just let him answer,” Gray writes.

“And after that, when I asked him something else, he answered, then said, ‘Mr. Gray, I love you,’ and he kissed me on the cheek.

“It was far more disturbing when he kissed me than when he threatened to kill me.”

When a 25-year-old Tyson was imprisoned for six years for rape in 1992, at the height of his boxing powers, he wrote to Gray from Indiana Youth Centre and said he could be released much earlier if he confessed to the crime. But, he wrote, he’d never do that.

“I will never admit to something I didn’t do,” the letter said.

Following that sentence, Tyson wrote that there were “four or five other things” he had done that were “worse than what I’m accused of,” concluding that it was probably right that he was in jail anyway.

Gray kept the letter. When Tyson was released in 1995, having served less than three years of his sentence, he got the first television interview with the boxer and asked him to his face: What was it that he did that was even worse than rape?

“Mr. Gray,” replied Tyson, matter of factly, “it’s probably best that I don’t answer that question on national television because I don’t know the statute of limitations.

“However, what I wrote you is true.”

It was during his time in prison that Tyson bought the first of his three Bengal tigers, a 250kg big cat called Kenya, costing him $71,000. He had been discussing buying a new vehicle with his car dealer but the conversation turned first to horses and then to wild animals. (Eventually, Tyson had to give Kenya up because — as Tyson once explained — the cat “ripped somebody’s arm off.”)

Today, he prefers to keep pigeons.

But Tyson is still fighting — and racking up the cash.

Last month, the boxer returned to the ring for an exhibition bout against Roy Jones Jr., 15 years after his last professional fight. Now 54, he appears to be in formidable shape, with a rock-solid six-pack and biceps like boulders. Though the fight ended in a draw, more than 1.2 million people paid $50 to watch on television, netting Tyson a reported $7.5 million for just 16 minutes work.

In February, he also opened Tyson Ranch, a 40-acre cannabis farm in California City in the Mojave Desert, 110 miles north of Los Angeles. Now a committed weed fan, Tyson even admitted to smoking the stuff before his fight with Jones Jr.

“Listen, I can’t stop smoking,” he told reporters. “I just have to smoke … I smoke every day.”

It’s just the latest chapter in what Gray calls Tyson’s “roller coaster” of a life. “He remains a complicated man, forever unpredictable,” he concludes in the book.

“Who knows what happens next?”

– New York Post