Yayoi Kusama: eight decades of art by the princess of polka dots arrives in Melbourne

Yayoi Kusama’s art has brought joy to millions worldwide – but her creativity began from a dark place. Read her fascinating life story ahead of her blockbuster NGV exhibit. SEE THE VIDEO

She is the princess of polka dots, an internationally renowned artist whose iconic works are staged and celebrated around the world.

Melbourne’s NGV also recently surrendered to her speckled delights, with a pink and black polka-dot work covering its grand waterwall entrance, accessorised by 60 trees wrapped in fabric bearing similar colours on nearby St Kilda Rd.

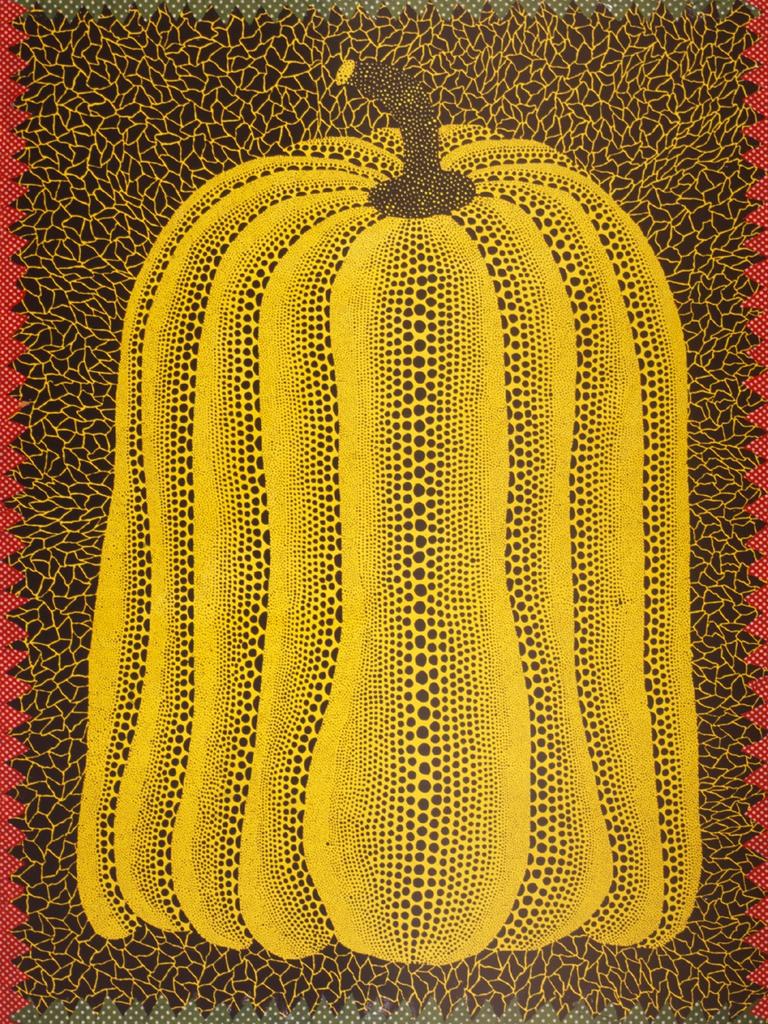

The public art, which also includes a 5m-tall yellow and black polka-dotted pumpkin — another favourite motif — in the NGV forecourt, is the opening round of a summer blockbuster exhibition showcasing contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama.

However, for Kusama, 95, the famous polka dots symbolise a lifetime of trials and trauma.

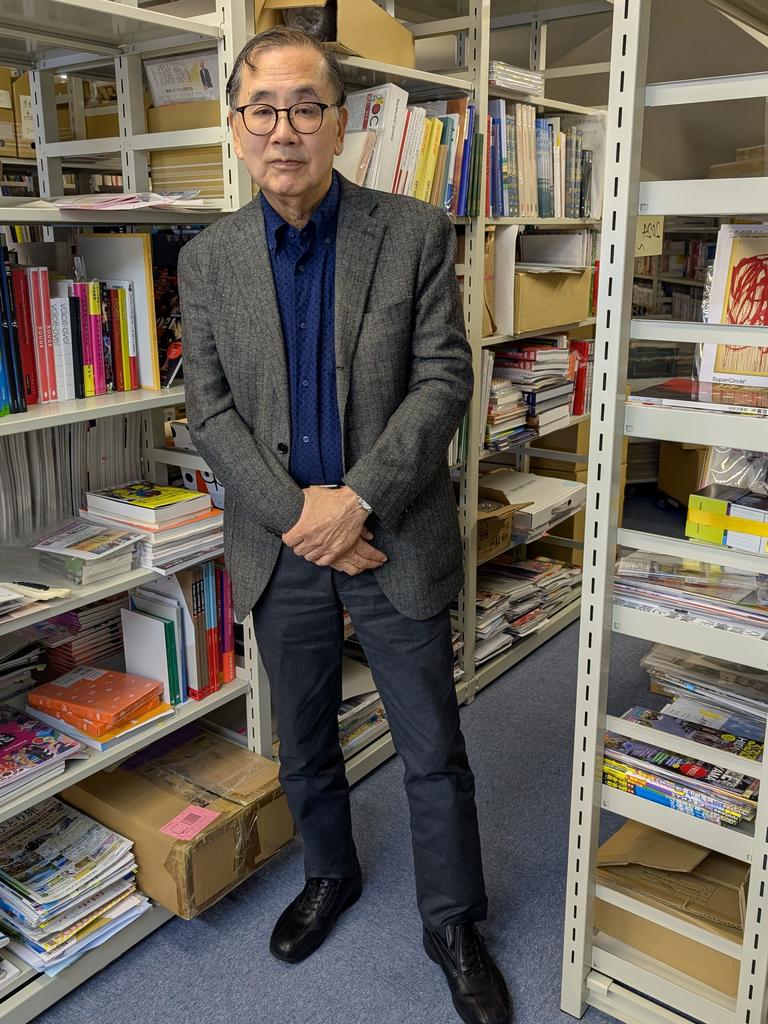

“Kusama has many obsessions. Obsessions with repeating patterns, especially the polka dots, is the most fearful for her,” Professor Akira Tatehata, director of the Yayoi Kusama Museum in Tokyo, tells V Weekend.

“But there’s a way to cope with fears by creating art. A healing process. Salvation.

“She releases herself from those obsessions by getting it out, by making art with it.”

The Japanese artist was born in 1929.

At age 10, she began to experience hallucinations, which she says in her autobiography, Infinity Net, comprised of “flashes of lights, auras, dense fields of dots.”

Kusama would see patterns moving, multiplying and swallowing everything around her. She called the process “self obliteration.”

Kusama also heard pumpkins, dogs and flowers talking to her.

“Whenever things like this happened, I would hurry back home and draw what I had just seen in my sketchbook,” Kusama wrote. “Recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episodes. That is the origin of my pictures.”

Kusama also had a disturbing childhood. Her mother was physically and emotionally abusive, and would force the young girl to spy on her father’s extramarital affairs.

She would later write: “The sexual obsession and the fear of sex sit side-by-side in me.”

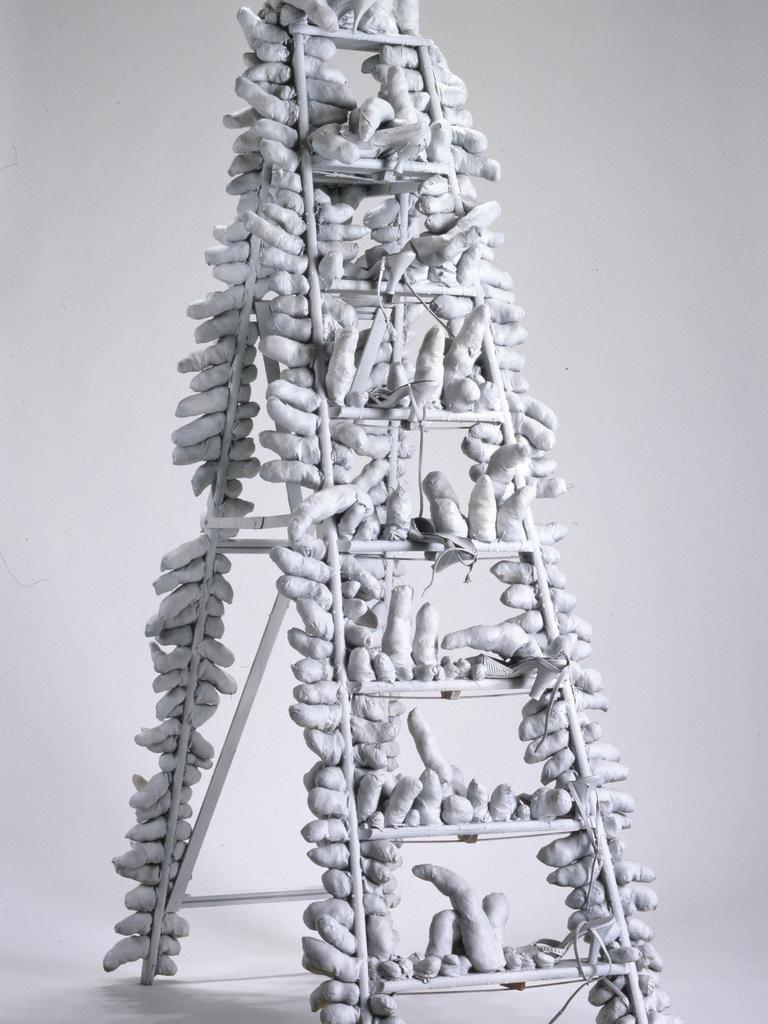

Some of Kusama’s of art contains sexual themes, and feature protruding phallic forms.

At age 13, she was sent to work at a military factory during World War II. She would often sew in a dark room terrified by the sound of air raid sirens.

“I fight pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and the only method I have found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art,” Kusama wrote. “I followed the thread of art and somehow discovered a path that would allow me to live.”

Professor Tatehata said art gave Kusama strength, and a broader mission.

“By sharing those painful experiences and traumas, Kusama is creating a platform for others to relate and communicate,” he says. “At first, she was trying to release her obsessions, but now it’s created this community for people to come together.”

He adds: “The timeline of her life is very dramatic. She had so many events in her life that influenced her to be the person she is today. She encountered events that no young girl should experience. The relationship with her parents was devastating. But those life events correlate directly with her art work.”

The Melbourne will feature 180 works by Kusama, including a kaleidoscopic infinity room, built exclusively for the NGV, and the Australian premiere of a new work; a structure that entangles viewers within 6m-high tentacular forms covered in yellow-and-black polka dots.

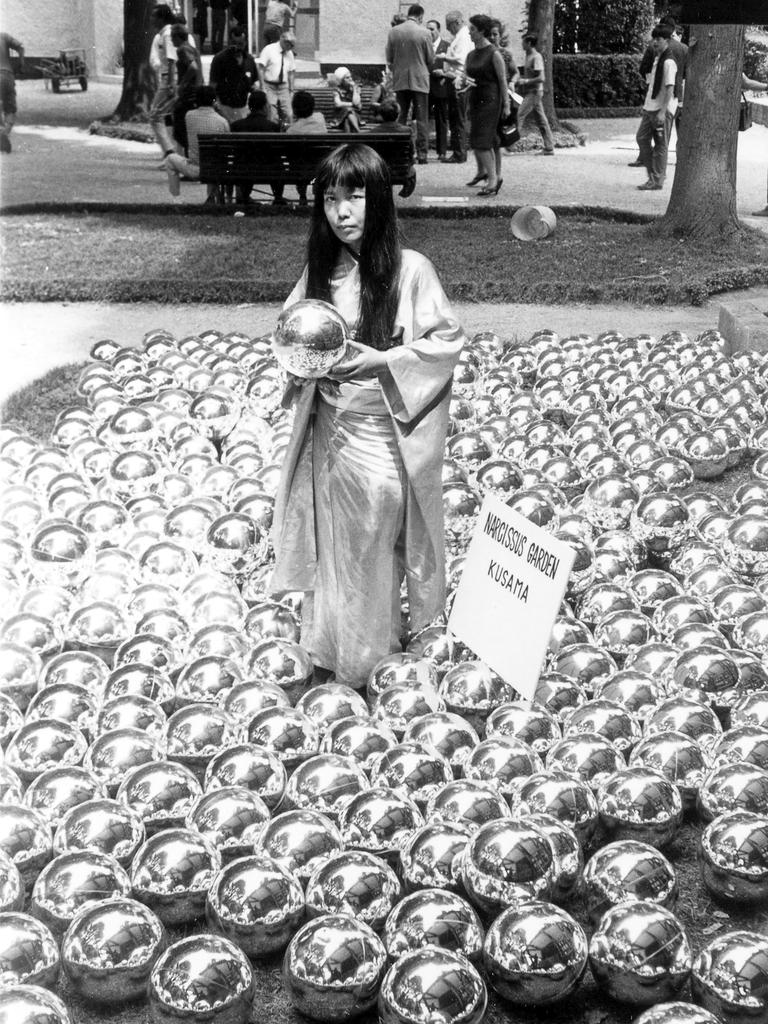

Another highlight is already on display as public art. Narcissus Garden, also in the NGV foyer, comprises of 1400 stainless silver balls. The reflection in each metallic spheres create an infinitely recurring landscape.

The exhibition also aims to tell the story of Kusama, who went from childhood in Matsumoto, and early success in Japan, which escalated in New York in the 1960s. Her minimalist, repetitive style inspired pop art contemporaries Claes Oldenberg and Andy Warhol.

Kusama’s New York period, from 1957 to 1972, included performance art, fashion design, activism and exploration of ideas like feminism and sexual liberation.

However, her radical experimentations in Manhattan didn’t translate well in Japan. She returned home in 1973 as the so-called Queen of Scandal.

“She came back to Japan to so many misunderstandings and criticisms,” Professor Tatehata said.

But Mr Tatehata was swayed by Kusama’s “genius” after seeing her collages at a small gallery in 1974. He worked slowly at persuading other Japanese art figures to reconsider Kusama as a legitimate talent.

“I was astonished,” he said. “I felt it was my duty to re-estimate her … and bring her back into the art scene. It took many years, but I succeeded.”

However, by 1977, Kusama’s mental state had deteriorated. She suffered severe depression and tried, for a second time, to take her own life.

A doctor recommended art therapy in hospital, and Kusama voluntarily checked herself into a Tokyo psychiatric facility, where she has been a patient — and artist — ever since.

“She has a huge room, where she continues to paint,” Mr Tatehata said. “She doesn’t lose energy to paint. Her work is so fruitful, with so many expressions; the paintings, sculptures, installations. It’s a mysterious force.”

Mr Tatehata takes phone calls from her, and visits Kusama, regularly.

“She is arrogant, powerful, and an anxious artist,” Mr Tatehata says. “She is also very charming and pretty. She has charming personality of a young girl.

“Her desire to self-obliterate and narcissism; they both simultaneously exist within her. The ideas of death, and living on forever, are both recurring thoughts and themes in her life.

“The pumpkins are a self-portrait,” Mr Tatehata says. “The pumpkin represents herself. I asked her, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘They’re pretty and funny.’ And they’re strong.”

Mr Tatehata laughs. “I believe the pumpkin represents her very well.”

Kusama skyrocketed back into popularity following a dazzling show, with mirrored rooms and pumpkins sculptures, at the Venice Biennale in 1993. Then, slowly, but surely, Kusama retrospectives surfaced in museums and galleries worldwide.

Later, as a new decade ticked over to the social media generation, her vivid, surreal and Instagram-ready work is more popular than ever. “Her art is liked by many people … across all borders, genders and ages,” Professor Tatehata says.

“She has created abstract work her whole life, but leans towards neo-pop works and objects the younger generation are more familiar with. Perfect for Instagram, right?” he adds, laughing. “Even on phone screens, you can feel the charm and energy and colours.”

Professor Tatehata will visit Melbourne for the opening of the NGV’s Kusama exhibition on December 14. He said the exhibition is important and inspirational.

“Her mental illnesses have never gone away and she is still fighting against those thoughts,” Mr Tatehata said.

But, he adds, Kusama’s work is about “a desire and belief that art will save the world … and a road that was built to save herself.”

Yayoi Kusama, NGV International, December 15, 2024, to April 21, 2025. Tickets: ngv.vic.gov.au

Originally published as Yayoi Kusama: eight decades of art by the princess of polka dots arrives in Melbourne