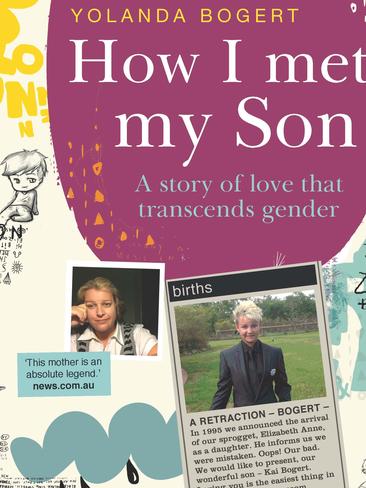

How I met my son: Yolanda and Kai Bogert share their story

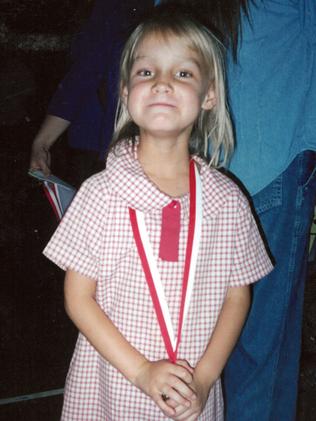

YOLANDA Bogert made the news worldwide when she placed a birth notice to mark her teenage son Kai’s coming out as transgender. They are now sharing their story.

KAI Bogert battled depression and suicidal thoughts. But when he finally came out as transgender, his mum marked it in the most beautiful way. They are now sharing their story in a new book:

YOLANDA Bogert made news around the world when she placed a birth notice in the Courier Mail in December, 2014, that read: “A retraction: In 1995 we announced the arrival of our sprogget, Elizabeth Anne, as a daughter. He informs us that we were mistaken. Oops! Our bad. We would now like to present, our wonderful son — Kai Bogert. Loving you is the easiest thing in the world. Tidy your room.”

The mother, now 36, and her son, 20, who live in semirural Jimboomba about 35km southwest of Brisbane, had interview requests from The New York Times and the BBC, and TV presenters camped outside their home.

Despite the positive awareness of transgender issues the notice raised, part of Yolanda wishes it never happened. In the book, the fulltime student nurse and Kai (studying for a mental health qualification) detail the effects of the story that went viral.

YOLANDA: I was torn between not wanting to make a big deal of Kai’s coming out — I didn’t think there should be anything abnormal about it — and wanting to commemorate that something special had happened. He’d done something so courageous and taken a huge step towards his own fulfilment and happiness, and that sort of thing warrants at least marking, if not a parade and fanfare. I wanted to borrow a normal milestone commemoration and tweak it to fit. The newspaper retraction fell in line with wanting to acknowledge that there wasn’t anything wrong with Kai, he’d just been ignorantly mislabelled before we understood — before we could understand — that he might not be so happy about being carved up to fit into the boxes in everybody else’s heads. I wrote a couple of quick drafts. The words “Loving you is the easiest thing in the world. Tidy your room” bumped the cost up from $56 to $70-plus, and

I ummed and aahed over whether to leave them in.

I was pretty broke that week, but it just didn’t sound right without those lines and, oddly, this wasn’t the first time I’d found myself torn between petrol and poetry.

I left Kai some money before I went to work, along with three different messages to make sure he went and bought a copy of the newspaper and then I couldn’t help it and stopped to buy one myself. I got some heavy butterflies and worried that he would be upset. Was this one of those awkward Mum things that I do, which I think are really loving and he thinks are way embarrassing?

I mostly managed to forget about it through the day, until I got a message from my partner to say that Kai wasn’t entirely thrilled when he first saw it. Bummer. But when I walked in the door that afternoon, he was on the phone with a journalist and seemed chuffed that someone else obviously thought it was a sweet thing to do and it was not something to automatically hate because Mum did it. Crisis averted. Being naive little petals that we were, our phone number was listed in the White Pages, along with our address, and we realised that the entire world had access to us.

It got a bit scary, especially considering some of the more vitriolic reactions from less-than-accepting people. For a while we felt unsafe, and I wished so very hard that I could take it back.

I had inadvertently opened Kai up to the scrutiny of the world, and there was nothing I could say to make it better. There was a smaller element of criticism about me outing Kai publicly as transgender that still bothers me today because it’s very reasonable. A handful of people who were discussing this expressed that they were worried about me deadnaming Kai. “Deadnaming” means using a transgender person’s old name even though you know that they’ve changed it. It can be done passive-aggressively, in a disrespectful refusal to acknowledge a person’s chosen name and invalidate a person’s transition, or it can be done maliciously as a way to deliberately hurt the person. Or it can be done thoughtlessly, as when a well-meaning doofus mother uses it in a birth announcement.

KAI: Mum stuck her head through my bedroom door as she was leaving for work. “I’ve left a couple of dollars on the kitchen bench — I need you to go down the road and pick up a newspaper. There’s something in it for you.” Ah s---. What’s she done now?

I went and picked it up with trepidation. Knowing Mum, it could have been anything. I read through the paper and was confused because I couldn’t find anything at first. It wasn’t until I saw it pop up in a post on Facebook that I flipped through to the classifieds section.

At first, I panicked a bit. Holy crap, now I couldn’t take it back. Not that I wanted to, but this made it seem much more real than it had until that point. I’m not a very extroverted person and being in the paper made me cringe. I wasn’t sure how to feel about it until that afternoon when the newspaper lady called to say that they’d had such a great response to the birth notice that she wanted to do a story about it in the next day’s paper. People were OK, even happy to see it — this was nice to hear, because that made it OK for me too. She asked me how I felt about it, and I don’t really remember what I said. Mum came home while I was on the phone, so she talked to the journalist next.

Neither of us thought much of it after that, even when she said that there was a photographer booked to come around right now and take pictures so that they could publish it the next day. We thought it was just going to be one of those little feel-good stories. The photographer put us at ease, and I liked the pictures that he took — I think it might be that these were the first pictures I’d seen of myself in a long while that showed me happy.

The next morning, the phone started ringing really early, and Mum was pretty stressed. I know that she thought she’d exposed me to the whole world and that she was worried about it — and it was pretty scary, sure — but I don’t blame her for that. It was overwhelming to be the focus of so much attention. Everybody was messaging me on Facebook and I was sent about 600 friend requests by people I didn’t know. Some of my favourite pages shared our ad, and there were thousands and thousands of comments.

The experience was a mixture of good and bad but mostly good. Some of the messages were from other trans kids who could relate, and others were from parents of trans kids. I loved hearing that — because they’d seen our story — things were going to be a little easier for them. That made me feel awesome.

YOLANDA: Towards the end of his senior year [in 2013], I had a call from Kai’s school asking me to come in to speak with him and the guidance counsellor. He’d revealed that he had been having suicidal thoughts. I don’t think I’ve ever been so afraid.

The noise in my ears drowned out the stranger in front of me, who was trying to tell me about my sprogget’s pain. Did she think I didn’t know? I’d helplessly watched it grow for years. I’d stood on what I realised was the other side of the wall that he’d built around himself, knocking my knuckles bloody trying to get him to open it.

Kai and I have debated how to write about this dark period for months. There’s still so much stigma that goes along with mental health issues and it’s not like Kai doesn’t have enough stigma to face already. But it’s important to both of us that the people out there going through the same thing (or similar things) understand that they are not alone.

The only thing ever going to really shake that stigma is people refusing to wear it. This is us, refusing to wear it.

It’s not fair to ask Kai to bare the inside of some of the darkest corners of his head to the whole world and stand out there all alone, so I will open mine first. (You might understand our reaction better if you know some of the history too.)

In February 1988, my father took his own life. My mother moved with me and my siblings from the UK to Australia in search of a fresh start but the shadows followed us. Mum and I struggled to maintain a relationship, and I found myself flitting between youth refuges, foster homes and street havens, each of which come with their own associated problems. I think that so much of the destructive power of mental health issues comes about because people spend so much energy trying to hide them.

In the interests of disclosure: Hi, my name is Yolanda and I suffer from PTSD, anxiety and depression. I am a survivor of rape, and I have experienced homelessness and dependency. What seems like a huge and significant part of my life was actually only a few years. At 15 I fell pregnant with Kai, and it was like the whole world suddenly righted itself.

Most of the time, a teenager with no resources and no prospects falling pregnant is not such a great thing, but I’m pretty sure that Kai saved my life. Sure, it was still relatively tumultuous and chaotic, but now there was the promise of a beautiful safe harbour of family for both of us one day. I hushed a thousand inner voices to make things right for him.

Cut to nearly middle age and we seem like every regular suburban family — to look at me, you’d never have guessed any of these things about me if I hadn’t told you. It took a long time, but I finally felt normal. Average. Mediocre, even. It was great. But I blinked, and suddenly my youth was gone and I was watching it replay in a sequelled version 2.0. How could I not have noticed that now we had matching scars?

The overwhelming misery I saw in his eyes made them just like a mirror. I had sat in exactly the same chair, and though I had been in such a similar emotional place (minus the transgender experience, of course), I still had absolutely no idea how to help him or what to say. I would have fought the whole world to protect him, but I had no idea how to protect him from himself on my own. I knew that it was something that needed real help, if not the hospital, so I took him to a local clinical psychologist who spent the afternoon with him, and we left with a plan.

We got home and did the only successful mental health treatment that I knew — we built a pillow and doona fort and shut the world out for a bit, hibernating like chocolate-biscuit-eating bears and watching episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Things were going to be okay. Not today, but eventually.

We slowly picked up the pieces of Kai together, and focused on hope and planning for the future. We talk about it pragmatically, because shame doesn’t belong attached to illness, and that’s how we will continue to confront it — for both of us.

KAI: It’s hard to reflect on my depression, especially given the context. I was lonely, sure, but I had a small circle of friends and supportive parents, and I was doing well in school. I didn’t understand why I felt so down and anxious all the time. I think that a big part of the bother of depression is guilt for feeling depressed because you don’t think your depression is justified. Towards the end of Year 12, so many things came to a head. I had been struggling with English and managed to conceal it until it mattered, during my end-of-year assessments.

My gender dysphoria gnawed persistently at the back of my consciousness, and the general emotional chaos of being 18 caught up with me. It was too much, and I found myself sitting, staring out, watching a whirlwind of panicked adults freaking out after I confessed to my student counsellor that I’d had suicidal thoughts.

Mum was called. Her history meant that we were both desperately trying not to lay guilt on the other. Me, hyper-aware that she would be reliving her dad, not living through this, and her, hyperaware that I was aware and trying not to let that overtake her looking after me. She was trying so obviously hard not to freak out that it was really freaky. You know how you try so hard not to cry when you’re upset, but that just makes you cry harder? That.

Neither of us knew what to say to each other. Mum kept talking round and round in circles like one of those pull-string dolls when the string gets broken. If it hadn’t been such a messed-up day, it would have been funny.

I spent a couple of weeks away from school, which was hard right in the middle of Year 12 final exams, but I’m glad that I didn’t miss them entirely, languishing in some shy Girl, Interrupted set. It would have meant a lot more catching up and recovery.

The hardest part was watching everybody around me walking on eggshells or handling me like a grenade with its pin taken out. I just wanted them to be normal. I just wanted everything to be normal. Nothing had been normal before, but maybe we could give normal a shot? It was crap. Really crap. But not as crap as it would have been if people had let go of the lifeline when I needed them to hang on for me, so I guess I could deal.

I still struggle with depression and spend a lot of time in my batcave (aka bedroom, which by the way you still haven’t tidied — Mum) [Yes I have! Get the feck out of my story, Mum! You have the whole rest of the book], playing Grand Theft Auto, but I have a bunch of coping strategies and a buttload of supportive family and friends, so the future is looking relatively bright.

I want to say that if there’s anybody out there in the same position, please don’t give up. Don’t give in. I won’t lie — you’ll be battered and bruised a lot when you come out the other side, but hang in there. For five more minutes. Then for five minutes more. Five turns into 30, and even in that short amount of time, things can look different.

This is an edited extract from How I Met My Son by Yolanda and Kai Bogert, published by Affirm Press. Available now at Big W, Target, booktopia.com.au and all good book stores, $24.99.

Anyone with personal problems can contact:

Lifeline (131 114), Mensline Australia (1300 789 978), Beyond Blue (1300 22 4636),

Victorian Statewide Suicide Helpline (1300 651 251).

Originally published as How I met my son: Yolanda and Kai Bogert share their story