The Australian towns facing a looming ‘day zero’ crisis

Australian communities are staring down the barrel of what authorities dub “day zero” — a crisis threatening lives and livelihoods.

Almost a dozen towns across regional New South Wales and southern Queensland are staring down the battle of a crisis that’s been dubbed “day zero”.

It describes the looming risk of running out of drinking water, as the ongoing drought continues to wreak havoc for tens of thousands of Australians in dry communities.

Local Government NSW president Linda Scott said a number of regional cities and towns are preparing for a day zero that’s less than 12 months away, with some expected to face it within three to six months.

“And in some areas, it’s probably a matter of weeks,” Ms Scott told news.com.au.

“This is very serious. Carting water in trucks for hundreds of kilometres on dirt roads is going to be the only way some councils can provide drinking water to locals.”

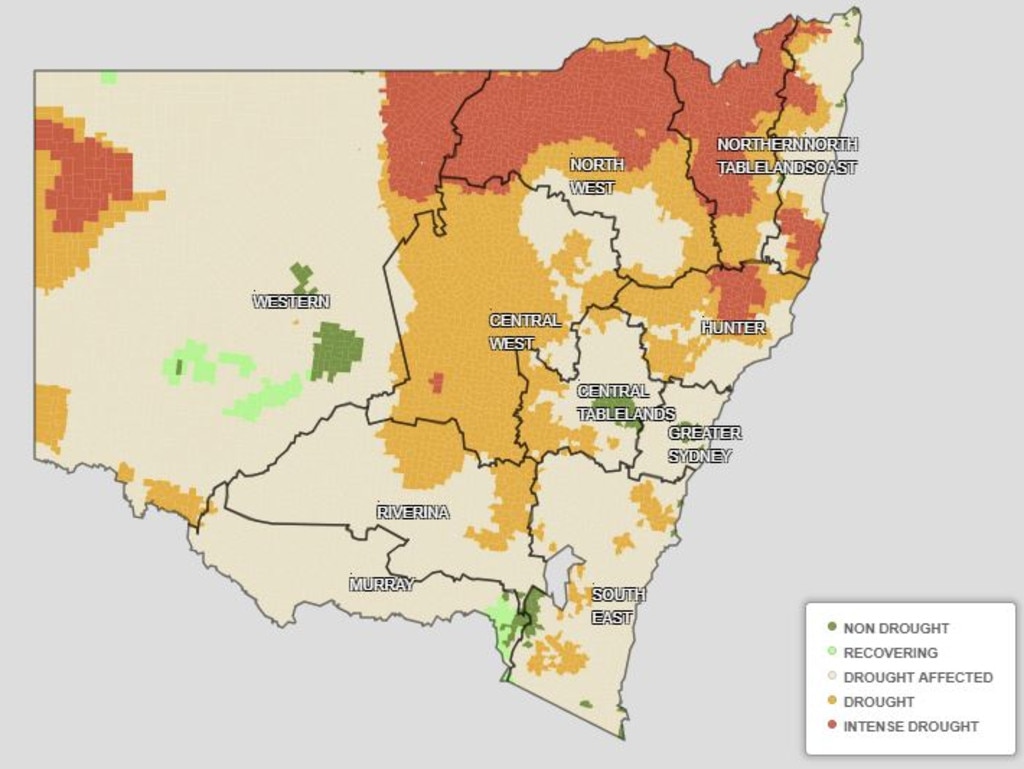

This map shows the areas that have been deemed “high risk” when it comes to dwindling water supplies.

Tenterfield in the state’s north is at the epicentre of the crisis, with the town’s dam sitting at a precarious 32 per cent and a single bore struggling to supplement the supply.

“We pump that bore for two days and then give it a spell for a few days, to let it replenish, and in those two days, it puts roughly a day’s use back into the dam,” Tenterfield Shire Council Mayor Peter Petty said.

“I’m no mathematician but to me that’s going out the back. It won’t last.

“Our concern is that if the bore sh*ts itself, we’re buggered. It’ll be 200 days left of water and we don’t want that to happen.”

Just across the border in Queensland, Stanthorpe could reach its day zero by Christmas, with nearby Warwick at risk of running dry in 17 months’ time.

“This is the worst drought we’ve ever had in our region and it’s really biting hard,” Southern Downs Regional Council Mayor Tracy Dobie said.

“We haven’t had rain since March 2017. In the past, it rains here in summer. That hasn’t been the case for a while now.

“The issue we’re facing is the dams and creeks are all dry and so the inflows into our urban water storages have ceased.”

RELATED: Daughter’s photo perfectly captures desperation of Aussie farmers

Extreme water restrictions are in place, limiting daily usage to 120 litres per person. Council has also conducted a leak audit of its pipe system to ensure every precious drop is maintained.

In addition to Tenterfield, Stanthorpe and Warwick, other towns making preparations for their own day zero scenarios are Tamworth, Orange, Dubbo, Armidale, Narromine, Cobar and Nyngan.

“It’s different in each area,” Ms Scott explained.

“I was visiting towns a few weeks ago that are soon going to need to transport water in trucks for hundreds of kilometres over dirt roads to reach drought-affected communities. In some areas, there’s already a need to help councils fund the carting of water.”

The logistics involved in transporting water in trucks are complex and the cost is substantial.

In Tenterfield, Mr Petty said calculations indicate the region would need 1400 B-double truck loads of water each month.

“If that happens, I’ll hang my head in shame. I will have failed the community,” he said.

RELATED: Inside a town dealing with the drought: How this rural NSW community is struggling

Council is in discussions with the State Government to help fund a $3.2 million project to search for new bores, he said.

“We sit on top of the Great Dividing Range here so we haven’t got a water system we can pump out of. So, we’re looking for two or three bores to supplement the water supply. Last week, the testing people have found four places of interest,” Mr Petty said.

“It usually takes 12 months, but we won’t be here in 12 months. We want to try to get it done quicker. We’ll get the test bores in and then we’ll find out how much is there, all that, it’s a long process.”

Ms Dobie said council could have to cart water from Warwick to Stanthorpe by the end of the year, which could cost as much as $1 million a month.

“We’ll take the water from storage in Warwick to keep Stanthorpe supplied. It means Warwick storages will be exhausted earlier. Once that happens, we’ll move to the use of production bores,” she said.

That’s one of several necessary measures to ensure locals never face a scenario where they turn on their taps and no water comes out.

“For Stanthorpe, day zero will occur sometime around Christmas,” she said.

“But I must qualify that. We can extend that out a bit by helping residents to use less water and that’s exactly what we’ll do. It’s about maintaining balance — an acceptable liveability standard combined with businesses, the minimum amount of water they can use.

“We won’t get to a point where you turn your tap on and no water comes on. We will not let that happen. We won’t be in a situation where we’re dropping bottled water at people’s front doors. We will continue to run an urban water supply.”

A spokesman for Orange City Council said the water outlook there was “much more complex” than other at-risk centres.

“Here, it takes into consideration factors like our storm water harvesting system, our water pipeline (and) the reduced water use due to tighter water restrictions,” he said.

The worst-case scenario in Orange is hitting day zero in the next 12 to 18 months, giving the town a bit more breathing room than others battling the impacts of the drought.

Mr Petty said his region was typically “a safe area” when it comes to dry spells and water supply, but it’s been at least two years since the last decent rainfall.

As a result, the whole Northern Tablelands region is struggling, he said.

Glen Innes is dry but they’ve got a good water supply. Guyra is buggered, they’re carting water in. Armidale and Tamworth are in dire straits.

Towns at risk of running out of water are implementing emergency management protocols to extend current supplies as long as possible.

Apart from that, the immediate hope is that it rains sooner rather than later.

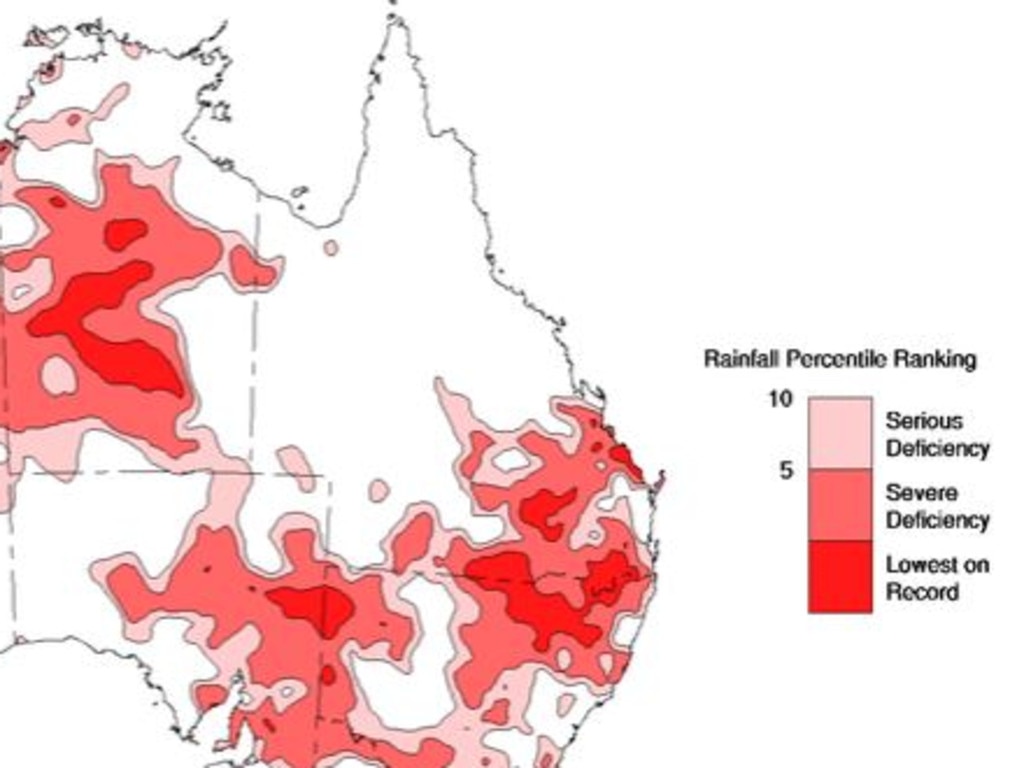

The Bureau of Meteorology said the past several months had seen below average rainfall for most of New South Wales and inland southern Queensland, with no reprieve in sight.

“The Climate Outlook for July to September indicates a drier than average three months is likely for large parts of the country, including most of the eastern mainland,” the Bureau said.

Locals in drought-ravaged communities are struggling, with spirits hit by the pessimistic weather outlook.

Mr Petty said his people are “very resilient” and, like him, hopeful of finding some good bores to keep things ticking.

But he admits the warmer summer months just over the horizon have him worried.

“I’m not a negative person but I’m being realistic when I say I don’t think we’ve seen the worst of it,” Mr Petty said.

“I’m off the land and I don’t see any long-range forecasts that are encouraging me that we’ll get a break in the season.”

In the Southern Downs region, Ms Dobie said locals are supporting each other as best they can, but some primary producers have had to de-stock while others have watched crops die.

“A bushfire is one thing, a flood is one thing, but a drought is horrific and slowly deteriorates your wellbeing,” she said.

Australians who live in metropolitan areas can provide some immediate relief, Ms Scott said.

“It’s a wonderful time to travel and see regional NSW and support these communities. It’s the most practical way of communities in the city to support the regions.

“Instead of going overseas, come to regional NSW and see the beautiful things on offer and inject some money into the communities.

“This is a practical way for Sydney to support their neighbours in regional NSW.”

Ms Dobie echoed the sentiment, saying her region was hardly “a moonscape” and offered plenty to entice visitors.

“We must maintain business as usual. We have to have our businesses continue to operate. We live in a beautiful part of Queensland and we want tourists to continue coming to our region, we want businesses to invest here and we want people to come live here.”

And Mr Petty said visitors would receive the warmest of welcomes in his part of the world, which he described as “dry but still beautiful”.

“We’d love people to come. Tourism is very important. It’s dry but it’s beautiful. Come and see us and support our local businesses.”