Rising number of Australians self-identifying as Indigenous may lead to government help being misdirected

The steady rise in the number of Australians identifying as Indigenous is, on its face, a good thing. But it comes with a tricky twist for governments.

There was a familiar trend in the data from last year’s Australian Census: once again, it showed a significant increase in both the raw number and percentage of people identifying themselves as Indigenous.

This was, on its face, a positive thing. But its implications for governments across the country as they seek to help disadvantaged Indigenous Australians are more complicated.

“An increasing number of middle-class liberal progressives are self-identifying, claiming their Aboriginality through a distant relative,” Suzanne Ingram, a Wiradjuri woman and academic at the University of Sydney, told Nine newspapers on Sunday.

She said the phenomenon was particularly occurring along Australia’s southeast coast.

Whatever is driving that phenomenon – one might highlight the rise of genetic ancestry testing in recent years, allowing people to trace their distant family trees with ease – there is a risk it will make it harder for governments to target those in need.

What the numbers say

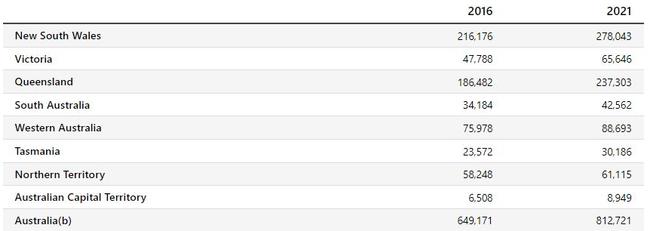

In the 2021 Census, 812,728 people identified themselves as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. That was 3.2 per cent of the total population.

There were 649,171 self-identifying Indigenous people in the 2016 Census, or 2.8 per cent of the total population. If you keep going back in time, that figure was 2.5 per cent in 2011 and 2.3 per cent in 2006.

“There have been significant increases in the number of people identifying as having Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin between Censuses,” the Australian Bureau of Statistics noted.

“Increases in population are influenced by demographic factors such as births, deaths and migration, and by non-demographic factors, including changes in whether or not a person identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in each Census, the identification of children or others who have had their form completed by parents or someone else on their behalf, and the impact of communications and collection procedures.

“It is important to remember that Indigenous status is collected through self-identification and any change in how a person chooses to identify with affect the count of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Census.”

‘Drawing money away’

You may have noted, from that data above, that the increase in Indigenous population was most highly concentrated in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria, with about 131,000 more people self-identifying themselves between the two Censuses.

In somewhere like the Northern Territory, by contrast, the increase was only 3000.

This has potential ramifications for government policy, as Census data is used by a range of government agencies, as well as organisations representing Indigenous Australians, to inform their policymaking and advocacy.

It’s an issue that some Indigenous advocacy groups have noted in the past. For example, back in 2017 the Yothu Yindi Foundation – which represents Indigenous people in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory – made a telling submission to a Productivity Commission inquiry.

The inquiry concerned Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation, which underpins the distribution of GST revenue to the states and territories.

The foundation argued that the existing system was “failing to assist either the Northern Territory or the Commonwealth government in their efforts to Close the Gap”.

One reason for that: the data used to determine where government services were needed was flawed, and failed to sufficiently identify the people in greatest need.

“We can find nothing in Commonwealth Grants Commission (CGC) papers that gives us comfort that the CGC methodology adequately recognises the vastly divergent circumstances of a family in Parramatta, NSW, with the parents having university degrees and being employed and owning their own home, with a family in Papunya suffering intergenerational welfare dependency, living in a humpy, with all of the socio-economic disadvantage that we know exists,” the foundation said.

“It is alarming to see that the Territory has, in fact, a declining share of the national Indigenous population. This cannot be explained by natural increases in population growth, but we assume it comes about because of lax census data, through self-identification.

“Indigeneity is an important factor in the equalisation process, and in our case it is drawing money away from the desperate need in the Northern Territory.”

In other words, there is a risk that the increase in relatively affluent people on the coast identifying as Indigenous will lead to poorly targeted policy, sucking help away from those in more remote and disadvantaged areas.

The opposite problem

There is an inverse problem to consider as well, however. Governments across the country have long been conscious that some Indigenous people are reluctant to identify themselves as such when accessing services.

A 2013 study by Aboriginal Affairs NSW found that barriers to identification included the difficulty of tracing one’s identity, concerns about the way the question was asked, and racism, discrimination and stereotyping.

“Identification is not the simple transaction that being asked to tick a box might imply. For some, being asked how they identify triggered painful emotions associated with traumatic experiences from their past and present,” noted the body’s general manager, Jason Ardler.

“Identification at government services is not static, for many changing over time in response to location and the service approach and environment.

“This has implications for our understanding of the changes we see in our service outcomes. What we observe as a change may be explained by Indigenous people’s assessment of whether it is safe for them to identify.”

Aboriginal Affairs NSW suggested boosting efforts to stamp out racism, ensuring people’s information is kept private, and increasing cultural awareness in the community.

One might say it was in that spirit that Premier Dominic Perrottet pushed to have the Aboriginal flag fly above the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

“Our Indigenous history should be celebrated and acknowledged so young Australians understand the rich and enduring culture that we have here with our past,” Mr Perrottet said last month.

“Installing the Aboriginal flag permanently on the Harbour Bridge will do just that, and is a continuation of the healing process as part of the broader move towards reconciliation.”

An international dilemma

The question of Indigenous identity is not unique to Australia.

In Canada, for example, there has been a debate over whether scholarship programs aimed at helping Indigenous people go to university are misdirecting too much aid to those who don’t truly need it.

“Today, it’s seemingly easy for people to claim indigeneity and self-declare by checking a box when applying for school,” Andre Bear, a former youth representative of Canada’s Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations and co-chair of the Assembly First Nations National Youth Council, wrote last year.

“People who claim to be Indigenous without the grief of intergenerational trauma – while enjoying white privilege and wealth – are consistently taking advantage of these programs in our schools.

“These programs are intended to help Indigenous people who are overwhelmed by real barriers such as institutionalised racism.

“It’s actually a step forward that Indigenous peoples are becoming more of a trend, because we now have a better opportunity to be represented. But we have to be careful about who we are uplifting while many oppressed Indigenous people are still being held down.”