Aurukun principal attacked for second time in two weeks as spotlight shines on ‘neglected’ community

THE community where women fight in the street and the school principal was attacked with an axe just got even scarier.

THINGS just got worse for the Far North Queensland community that last week made headlines for all the wrong reasons.

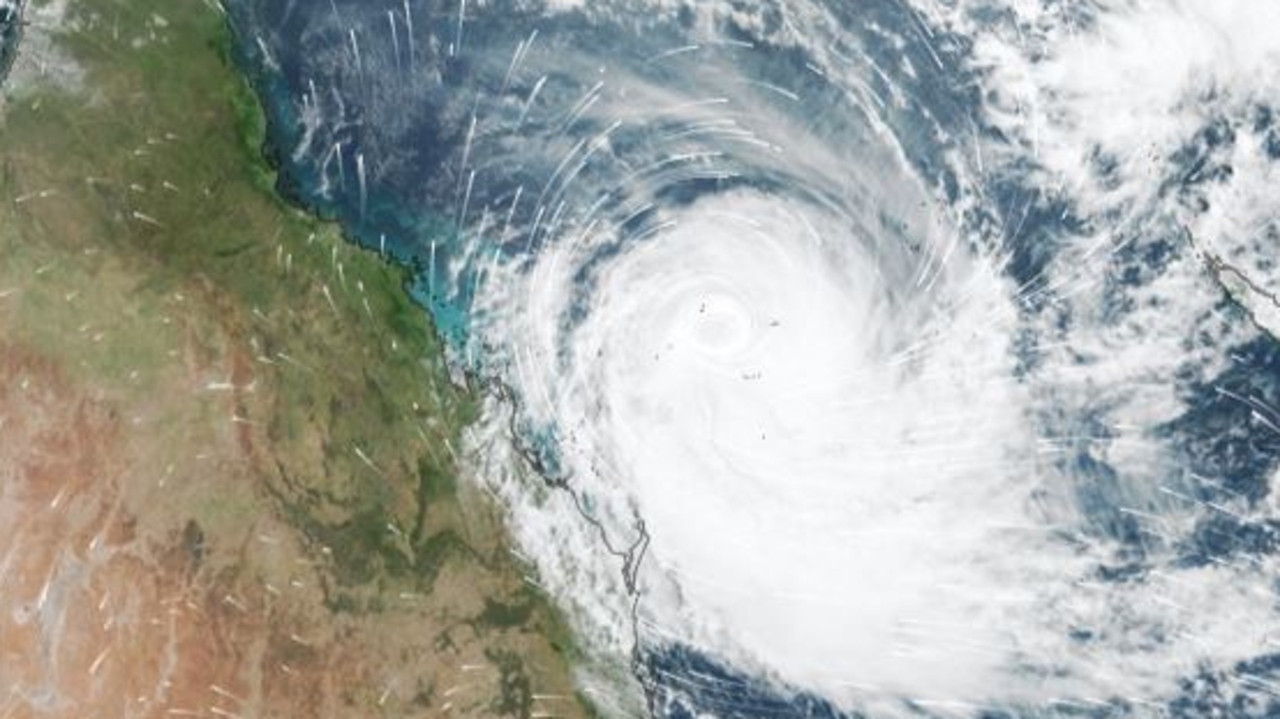

The Aboriginal township of Aurukun, on the west coast of the Cape York Peninsula, was the setting for a series of violent acts.

First, teachers were evacuated from the community’s only school after principal Scott Fatnowna was attacked with the back end of an axe. Then women were filmed throwing fists at each other as police stood by and refused to intervene.

As of Monday morning, things are no better. On Saturday night, Mr Fatnowna was carjacked and threatened with weapons for a second time in two weeks.

Police say a group of armed teenage boys approached the man and his wife on Saturday night where they stole the couple’s vehicle and took it for a joy ride. Three teens have since been tracked down and charged.

The initial attack prompted the closure of the school and the evacuation of 25 teachers. Queensland Teachers’ Union president Kevin Bates told The Courier Mail teachers “are on the threshold” of walking away from the remote township that is home to 1200 people.

It was reported on Monday that police will begin providing escorts to teachers in Aurukun. Police said they did not believe Mr Fatnowna was being targeted for who he is but “I think he has been targeted because he has been present when they are roaming around”.

David Martin moved to Aurukun in the 1970s and has dedicated his life to improving the lives of community members. The anthropologist told news.com.au on Saturday Aurukun has been “abandoned and neglected”.

He says what Australians are seeing is “a truly extraordinary community” and “a lost generation” but it’s not their fault. Take a closer look, he says, and the real problems are everywhere.

REAL PROBLEM WITH POLICING IN THE TOP END

A 2011 report declared Aurukun had one of the worst murder rates in the world.

Last year alone there was the shocking death of a man who was run over as community members watched, there were shots fired at police, there was a hammer attack and there were riots.

Footage of women fighting in the street hasn’t helped. In the footage, police are seen standing by their vehicles and watching the women brawl. It’s hard to look at, but it’s normal behaviour, they say.

Assistant Police Commissioner Paul Taylor defended the inaction by police. He said it was a matter of protecting the wider community.

“On occasion, the temperature within the community can raise quite rapidly because of one minor incident,” Mr Taylor said.

“Often, when police get to these incidents, there are large numbers of spectators and the complexities in Aurukun mean those people are all related to the combatants, and they are highly emotionally charged.

“If they do intervene, are they going to take it from a fair fight between two individuals to having a large mob, who are highly emotive, start fighting? On occasion, for the greater good of the community, it’s extremely difficult for us to intervene.”

The problem is bigger than that. One reason it’s so difficult for police in Aurukun is because many of them are rotated in and out from Cairns. It means they never get to know the community and, perhaps more importantly, the community never gets to understand them.

“Police have a very difficult job,” Dr Martin said.

“In the emphasis on maintaining law and order in very difficult circumstances, what is missing in terms of policing is community engagement. In recent months there have been contingents of Cairns police rotated through on six-week shifts.

“They never get to know the people that way, they never get to establish meaningful relationships with the community, including those who are ‘ringleaders’ in fighting. Police don’t really know who the key people are, and the potential for escalation when police arrive at a fight is huge.

“If they were known to and trusted by all sides, and if the police in turn knew something of the individuals concerned, then I believe those involved in fighting would be more receptive to intervention. Both sides need to know the other.”

DRUGS, ALCOHOL AND DISCONNECTED YOUTH

There’s a watch house in Aurukun that, at any one time, is likely to have many young people locked up. It’s a Bandaid solution to a much bigger problem.

There’s been a demographic boom and there are more young people in Aurukun than ever. Most feel alienated from the rest of Australia but also find it difficult to connect with their own cultural leaders.

“It’s a lost generation,” Dr Martin said. “Old people in Aurukun tell me it’s a lost generation, that young people don’t listen to them and they are heart sick about that.”

He said young men in particular are looking for a way to express themselves. They have leadership skills and energy but they’re channelling them into the wrong areas.

“What we’re seeing with the violence in Aurukun is increasingly the kind of group violence that we see in urban areas, in gangs in some other remote Aboriginal communities, and in the urban US.

“What the wider world offers in terms of education, employment and the like is not seen as meaningful for far too many of the young men. What their own society has to offer is also rejected. They do not seem to respect law and culture in the way previous generations did.”

He said the lives of young people in Aurukun are characterised by boredom.

“There’s a lot of energy and creativity and they see no outlet for that. The ringleaders are ringleaders often because more than others they understand the hopelessness of their situation, and react to it. They have leadership and creativity and energy, but it is being directed in an anti-social direction.

“We need to work with those ringleaders to see if they can’t be engaged. Locking them up only perpetuates the problem.”

Aurukun is made up of five ritual groups comprised of often antagonistic families with origins in different parts of Wik country. They all live jammed together in a remote version of housing estates with no escape from conflict which they find impossible to manage.

It’s a “dry community”, meaning alcohol and drugs are banned. But the reality is that drinking and using drugs is a big part of community life. There are problems with domestic violence, too, and children missing school.

In 2008, Aurukun, along with eight other communities in the Cape, signed up to a government-supported welfare reform project, but the money isn’t going to the right places.

Aurukun Mayor Dereck Walpo told the ABC this week he doesn’t know where much of the money has gone.

“A lot of money has been spent in this community over the last eight years but where’s it all gone?” he said. “I wish I knew. Where’s all the positive outcomes?”

THE GOVERNMENT IS WATCHING, PREMIER SAYS

It would be understandable for residents to feel like they’ve been abandoned but Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk says that’s not the case.

“I’ll be catching up with the Police Commissioner today for an update but we actually have a whole-of-government approach and my director-general will be travelling up there next week,” she said.

“We are closely monitoring the situation but I am very determined to make sure that people in that community get access to jobs.”

Watching is a theme in Aurukun. The State Government is watching. Police are watching. Some locals say it’s part of what’s going wrong. Too much watching and not enough action.

“They would not do that in other places in Australia, so why should they do that here,” Aboriginal leader Phyllis Yunkaporta said on Wednesday, referring to police standing by idly while women traded blows.

“What message does it send to a child to see a fight and police standing by and watching?”

Police are holding a press conference at 11am on Monday morning to address the latest incident in Aurukun.