On anniversary of discovery of message in a bottle, Brisbane socialite was a rising star and had many lovers before disappearance

It’s been over 80 years since the mysterious disappearance of a Brisbane public servant and socialite who vanished from a train station.

“I received £10 to dispose of the body of Miss Norval.

“She was dumped in the bay near Amity Point on 16-11-38 and I have since gone to N.Z.”

This was the creepy message in a bottle found 80 years ago this week in Queensland.

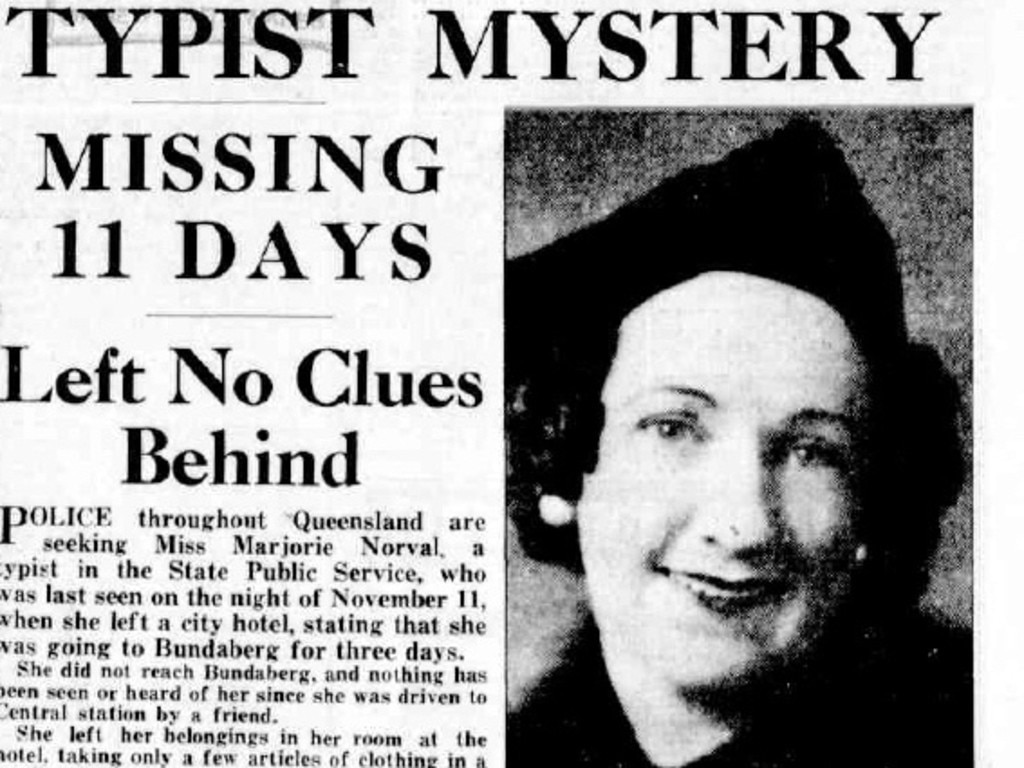

The writer was referring to Marjorie Norval, a 30-year-old Brisbane socialite and public servant, whose disappearance shocked Australia, with the case attracting the sort of attention Teacher’s Pet is getting today.

Ms Norval was last seen half an hour after sunset in Brisbane on Armistice Day, Friday 11 November 1938. Getting out of a car at Central Railway Station, she vanished without a trace.

Standing 5’6” with a medium build, short dark hair, a freckled complexion and striking blue eyes, Ms Norval cut an attractive and stylish figure in a dark dress and white hat.

She was also a rarity for her era: a modern career woman, who worked as a typist in the Chief Secretary’s Department and acted as trusted personal assistant and social secretary to the wife of Queensland’s premier.

One of five children, Ms Norval was born in March 1908. Her father, James, was a wharf labourer, and her mother, Rose, looked after their modest middle-class home in the inner Brisbane suburb of West End. Growing up, Ms Norval was a good student, making the honour list of her state school and doing well in her music exams.

In 1924 at the age of 16 she obtained 18th place in the Queensland public service examinations and started work as a typist in the Education Department. By 1925, she was enjoying social activities with her department’s social club and attending the coming-of-age parties of her older friends.

Attractive and charming, she met and dated a widowed optician named James East, who was nearly 30 years older than her.

After coming of age in 1929, Ms Norval’s social life accelerated. She’d be found at bridge evenings, club dances, the races and theatre opening nights.

While Ms Norval enjoyed everything Brisbane’s society had to offer, she was also a hard worker who rose steadily in the public service.

After working with the Education Department and at Parliament House, she transferred to the Chief Secretary’s Department in October 1932.

When Premier William Forgan-Smith went interstate or abroad, his deputy, Percy Pease, would be Acting Premier. With this the case in June 1934, Ms Norval was chosen by Percy Pease to assist him in the government’s Loan Council.

It was a historic moment for Queensland: she was the first woman to attend a meeting of this council and was also the youngest person to ever enter the assembly. She was “thrilled to bits!”, she told the Courier-Mail.

By mid-1935, Ms Norval’s duties had expanded to include acting as social secretary to Euphemia Forgan-Smith, wife to the premier Forgan Smith.

Though she worked hard, she enjoyed travelling and entertaining, taking her sports car on road trips and hosting friends for games afternoons and dance and dinner evenings at her Kangaroo Point apartment.

By the mid-1930s, Ms Norval’s best friend was Mercia Doran. Ms Doran was also single, social and a rising public servant. In late 1937 the two girls moved into the Albert Hotel, one of the city’s social hubs, located next door to the Tivoli Theatre and looking out on King George Square.

Soon after, Ms Norval and Mercia Doran went on holiday with the premier’s wife, Mrs Forgan-Smith, and the deputy premier and his wife, staying at the Surfers Paradise Hotel.

At a big party there Ms Norval met a man named Jack Caton. Like her long-time friend James East, Jack was an older widower, and worked as a travelling representative of the Ford Motor Company. She and Jack started dating.

Around this time, she was also “friendly” with Dr Peter English, who was yet another well-to-do widower. Then there was John Carey, a shop assistant of Gympie, who she dated casually from the start of 1938. He was only five years older than Ms Norval, though he’d been married for five years.

Albert Townsend was the Canberra-based chief investigations officer with the Customs Service, was also married, and nearly 20 years her senior.

Another rumoured lover was George Pollock, veteran politician and speaker of the Legislative Assembly. He was also nearly 20 years older than Ms Norval and though married had been apart from his wife for the past 15 years under a deed of separation.

She tried to keep her love life discreet but what she didn’t know was that she was being watched. Two night cleaners at the Tivoli Theatre had a clear view into her room the Albert Hotel.

For about six months, these creeps peeped by night at Ms Norval in varying states of undress and with her gentlemen friends.

From August to October 1938, she often complained of stomach trouble — sometimes in the morning — and bowed out of Brisbane’s social scene for a few weeks at a time.

Around this time she also told her sisters that she hoped to get a job at the Agent-General’s office in London. She sold her beaut little sports car, banking the proceeds in anticipation of making her move to England. But the job didn’t come off, though she still hoped to move to England.

MS NORVAL TELLS OF MISSION

In early November, she confided to her friend and roommate that she had been given a mission: to drive Mrs Forgan-Smith’s sister, a patient at Willowburn Mental Asylum, in Toowoomba, to Maroochydore or Caloundra.

Ms Norval soon after told Mercia that the trip had been delayed by a week. Meeting with her sister Gladys on 9 November, she said she was going away to the north coast for a few days on confidential business for Mr Forgan-Smith — and that he’d instructed her to tell her workplace she had to go to Bundaberg to look after a sick relative.

On the morning of Friday 11 November she went to work as usual. There, she applied for emergency leave, saying he had to go to Bundaberg to visit a sick relative, and planned to return to work on Wednesday or Thursday at the latest.

She told Mrs Forgan-Smith the same story. But her aunt in Bundaberg had received a letter from her saying she was going to Southport.

During the day, Ms Norval withdrew £30 from her savings account and changed other notes to the value of £20. Fifty pounds is the equivalent of $4500 today and represented about three months’ salary.

Ms Norval called James East and asked him to pick her up at the Albert Hotel that evening to drive her to Central Station. That afternoon, she also saw her friend John Carey, who was departing that night on the train for Gympie.

He said goodbye to her and said she appeared cheerful. Ms Norval finished work at 5pm and returned to the Albert Hotel to have dinner. She saw Mrs. Merle Weller, licensee of hotel, around 6.20pm. In a joking tone, she told her she was going to Bundaberg do a “little detective work for her department”, and would be staying at the Royal Hotel there for about four days.

James East said he found Ms Norval ready when he arrived at 6:45pm. After the short drive, he pulled up at Central Railway Station.

“Don’t wait till the train goes,” she said. “Go along and play your bridge”, which she knew was James East’s habit each Friday night at the Tatt’s Club. She got out of the car, saying, “I will see you on Thursday,”

“Don’t forget the tickets.”

This, he later said, was in reference to a show they were seeing the following week.

James East watched Ms Norval walk towards the entrance of the railway platform.

She was never seen again.

Six days later on Thursday the 16th of November, Ms Norval hadn’t returned to work.

On Saturday, her worried sisters contacted the police, who began inquiries that day. Searching her hotel room, they deduced, with her roommate Ms Doran’s assistance, that Ms Norval had only taken a pair of silk pyjamas a kimono with her in a small attaché case.

Three corsets were found, of increasing size. That, along with Mercia telling them Ms Norval had suffered stomach trouble on recent mornings, and medications used to induce miscarriage, led police to suspect the missing woman had been quite a few months into pregnancy.

Police also found a torn up letter. Sticking it back together, they found it was dated November 9 and from Albert Townsend.

He had addressed it “Dearest Marjorie” and signed off, “From yours ever, Albert.”

When questioned Mr Townsend claimed that, as a married man, his interest in Ms Norval was strictly platonic and restricted to what they had in common in regard to sickness and politics.

Interviews with her sisters, relatives, friends, workmates, along with James East, Ms Doran and hotel keeper Merle Weller showed she had gone to bizarre lengths to keep her true destination and purpose a secret.

Visiting an aunt in Bundaberg, going to Southport, driving Mrs Forgan-Smith’s mental patient sister, doing detective work for her department: the different stories were bewildering.

Just as bewildering was how this well-known young woman had vanished.

No-one had seen her at the railway station. Critically, there was no train to Bundaberg until 9pm, two hours after she’d arrived.

Furthermore, the railway station entrance she’d used led to southbound trains.

On November 22 1938 — 11 days after she was last seen — the missing woman was front-page news and by the end of the week the police search for her was the biggest in Queensland’s history.

But, increasingly the police feared she had met with foul play.

A £500 reward was posted for information leading to the discovery of Ms Norval or her remains.

Police interviewed about 800 taxi drivers, working on the theory that Ms Norval might have hailed a cab from Central Station after James East departed.

They searched Moreton Bay foreshores because it was speculated that if she’d been buried in sand then Friday’s strong winds might have uncovered her corpse.

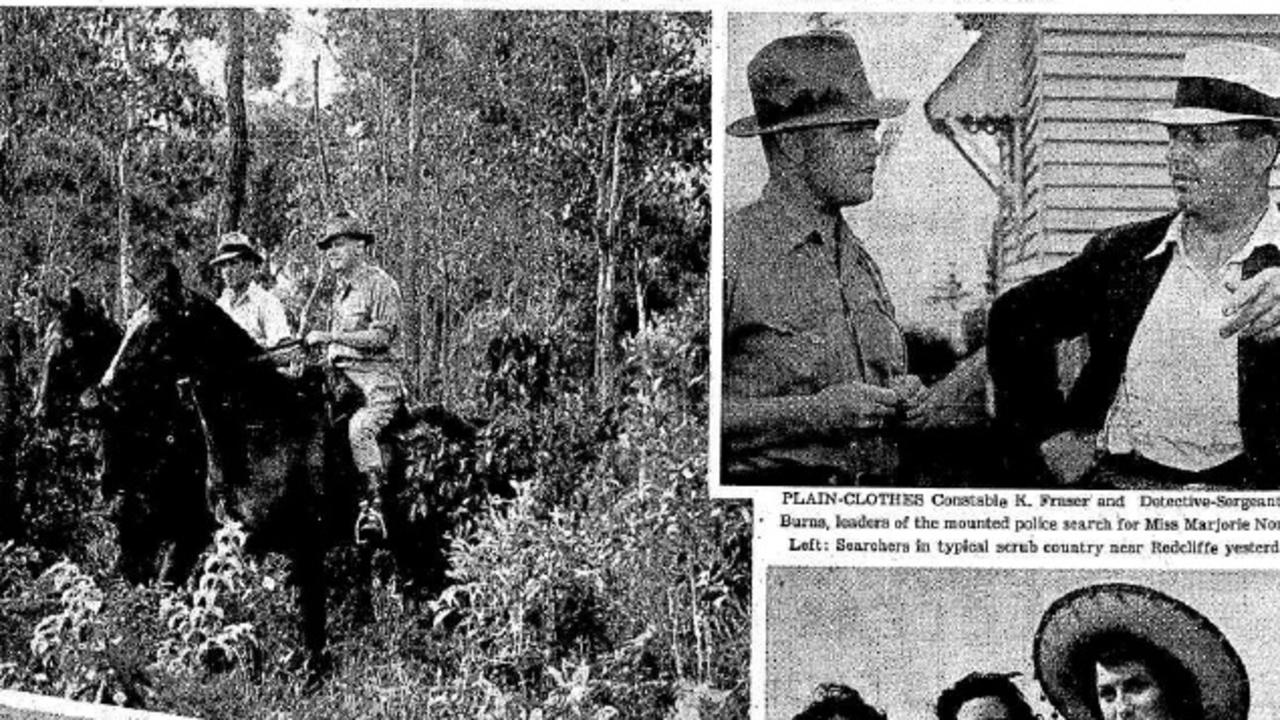

By November 28, a week into the search, six mounted police had covered 5000 acres around Redcliffe and Sandgate.

It was hard going, with horses sinking into swamps and the cops injured on falls and relentlessly attacked by mosquitoes. On Sunday November 29, thousands of Brisbane people organised themselves into unofficial search parties, scouring remote bush and beach spots.

RAAF TRAGEDY IN THE SEARCH FOR MS NORVAL

The search for Ms Norval that day also took to the air after the RAAF volunteered a Seagull Amphibian plane.

The plane took off just before noon. Its mission was to fly low so that Constable Young and the airmen could look for any sign of Ms Norval on the dozens of small islands at the southern end of Moreton Bay.

Seeing no sign of her the plane flew up the Albert River towards Beenleigh. At 12:40pm, no-one in the cockpit noticed the high-tension electricity cable stretching across the river between two 100-foot high steel towers near Alberton Ferry.

There was a brilliant flash as the plane hit and severed the wire, tearing off one of its landing floats.

The plane flew on with a long live cable caught on its wings and trailing to the river where it sent up blue flames when it touched the water’s surface.

Then the plane suddenly veered, yanked to earth by the cable, and smashed to earth through mangroves, wings tearing off as the fuselage exploded into flame. Everyone aboard burned to death.

Whoever was responsible for Ms Norval’s disappearance now had four more lives on their conscience.

By the end of November police favoured the theory that she had died after seeking medical treatment. This was, in the discrete language of the day, the police saying she’d sought out an abortion.

The search continued through December with the mounted police covering more than 50,000 acres and riding some 3000 miles.

By the middle of that month, Henry Gaggin, a fisherman, contacted police and said he remembered seeing Ms Norval at the Caloundra holiday home of Dr Arthur Ross, a man suspected of performing illegal abortions, the day after she disappeared.

But the cop who investigated, Detective-Sergeant Frank Bischof, later to become corrupt Queensland Police Commissioner, hastily decided that the woman Henry Gaggin had seen was Mrs Ross, though he didn’t make an effort to conclusively establish her actual whereabouts that weekend — or those of Dr Ross.

Author Ken Blanch, who wrote a 2014 monograph entitled Marjorie Norval: The Girl a Railway Station Swallowed, favours Dr Ross as Ms Norval’s killer and thinks his political connections saw him protected.

Just after Christmas a man at Wellington Point got the fright of his life when he touched a woman’s head while swimming in four or five feet of water. Police descended.

A search was made of the water and foreshores.

No body was found and it was thought the man might’ve mistaken brushed a sea sponge. This was just one of the 110 times Ms Norval’s body was “discovered”.

On January 13 in 1939 the message in the bottle was found by two fisherman at Southport. The police concluded the letter was a cruel hoax.

With all leads exhausted, and no new witnesses or evidence, the search wound down.

In early 1939, as the search was winding down, George Pollock, the speaker of the house, was losing his mind.

Seven years earlier, he’d had an agonising gastrointestinal complaint that had led to surgery. Since then, he’d often suffered pain and this, it was thought, was what had led to his depression. On Friday March 24 he locked his office door in state parliament and took his own life.

George Pollock was friends with Dr Ross, which, combined with his supposed affair with Ms Norval, led some to believe he’d ended his life out of guilt, rather than because of his physical pain.

It wasn’t until 1942 that Ms Norval was in the headlines again, courtesy of Member of the Legislative Assembly, Frank “Bombshell” Barnes.

This eccentric Queensland politician, who wore a pith helmet, made sensational claims that he had information about the case.

He asked for parliament to change the laws so a coronial inquest could be held without a body having been found.

They did — and it began in May 1943. Over three weeks, 20 witnesses were called. Ms Norval’s sisters, Ms Doran, Henry Gaggin, the hotel keeper Merle Weller — they all repeated their stories.

Ex-premier Mr Forgan Smith emphatically denied having told her to concoct the Bundaberg story to cover up her true mission.

Mrs Forgan Smith said she’d always thought Ms Norval truthful but denied having had a sister or any relative in any mental institution.

Dr Ross wasn’t called — he was then interned as a possible Japanese agent after his arrest in 1942.

Even 80 years later, simply from newspaper reports of the proceedings, inconsistencies are glaring.

James East, despite having emphatically told that Ms Norval had not mentioned Bundaberg to him, now told the inquest she had told him she was going there to visit a sick aunt. He wasn’t queried about this contradiction.

He also said he hadn’t known she was pregnant, that he couldn’t have been the father and that he had no idea Ms Norval was seeing other men.

Jack Caton was allowed to deny that he’d impregnated Ms Norval and that he’d ever been in her hotel room late at night. He admitted to having embraced her but denied going any further.

Albert Townsend was subpoenaed but didn’t appear on medical grounds that he’d been bedridden since 1941. By letter, he denied that he’d been intimate with Ms Norval.

Widowed, estranged, married or single: it seemed every man in Ms Norval’s life was simply a good friend.

Not that anyone believed this, thanks to the voyeuristic Tivoli cleaners. The cleaner who testified shamefacedly confessed to his creepy peeping on Ms Norval and her male visitors.

BOMBSHELL CLAIMS

Bombshell Barnes, who’d made the coronial inquest happen, detonated it with his wild claims. He sensationally said that Ms Norval had been shanghaied to California in order to stop her blackmailing now ex-premier Forgan-Smith and that there had been a cover-up ever since. When Bombshell refused to divulge his sources for these and other claims, he was fined and sent to jail for contempt.

Then, returning to court, he claimed a detective named “Smith” and a citizen named “Jones” had told him these stories.

If this political gadfly had genuinely wanted to know what happened to Ms Norval — rather than just use his time in the spotlight to hurt his political enemies — what he said and did had the opposite effect, shifting the focus to wild conspiracy theories when the inquest should have been pressing police and witnesses harder to zero in on the actual conspiracy.

Clearly there was a conspiracy. Ms Norval had fallen pregnant by someone who wasn’t confessing culpability.

She had died at hands of a person or people unknown, who’d then disposed of her body.

After three weeks, this was the coroner’s conclusion — that Ms Norval had gone to an unknown location to procure an abortion and had not left the premises alive.

EIGHTY YEARS ON

80 years later, the mystery of Marjorie Norval is as frustrating and bewildering as it was in the weeks after her disappearance and during the 1943 inquest.

Why did she tell so many stories about where she was going?

If she’d told everyone she was going to Bundaberg to visit a sick relative, it’s unlikely anyone would have questioned her further. Her first story — about transporting Mrs Forgan-Smith’s mentally ill relative — was so specific that it begs the question: Why tell a lie that, if discovered, could have ended her career?

James East’s account was all that anyone had to go on about the last known 15 minutes of Ms Norval’s life. But some angles of his story didn’t make sense. There were the contradictory accounts of whether she had told him she was going to Bundaberg.

His statement to the Truth saying he didn’t know her destination beggars belief: who takes a friend to the railway station without asking where they’re going?

Further, why had she even called him for a lift?

It was just 400 metres from her hotel to the station and she was only carrying a small attaché case.

It’s possible he drove her not to the railway station but to an abortionist and then lied to cover his own complicity when she died.

Jack Caton, meanwhile, was adamant he’d only seen Ms Norval three times “at the most” in their relationship.

But his testimony — that he’d seen her at least twice at Surfers Paradise and had twice been in her hotel room — contradicted that.

How could he be so sure he hadn’t gotten Ms Norval pregnant? His testimony, like that of other men, was allowed to protect his “honour”.

As for George Pollock, there seems more to his sudden descent into suicidal depression and derangement than physical pain he’d known for seven years already.

Certainly, if he was involved with Ms Norval and sent her to Dr Ross for an abortion and she’d died during the procedure, he could have been wracked by guilt — guilt intensely magnified by the deaths of the four men aboard the search plane.

Ms Norval may one day speak from beyond the grave. In June 2016, human remains were found in a park in Teneriffe Drive, in inner city Brisbane, briefly stirring interest in her case. But it wasn’t her.

Yet it’s possible that she’s still out there somewhere, her body perhaps bearing or buried with clues that could finally solve the mystery of who killed Marjorie Norval.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Michael Adams is the author of Australia’s Sweetheart, about forgotten movie star Mary Maguire, which is published by Hachette on 29 January, and he is the creator of the podcast Forgotten Australia, where you can hear more unknown Australian true stories.