‘Losers with no authority’: Inside the twisted beliefs of Queensland’s murderous Train family

The murderous family who gunned down two officers and a hero neighbour may have been motivated by a shadowy – and dangerous – belief.

When Jerry and Joe Kane were pulled over for a routine traffic stop in Arkansas in 2010, nobody could have predicted two officers would soon be killed in a devastating hail of bullets.

Now, more than a decade later and half a world away, an eerily similar case has left Australia reeling – with one core belief linking the Kanes and Queensland’s murderous Train family.

Jerry Kane and his 16-year-old son Joseph were part of the sovereign citizen movement, a far-right conspiracy theory that views the state – and authorities – as illegitimate.

Within moments of being pulled over, Joe Kane jumped out of the vehicle and shot dead two officers with an AK-47 assault rifle, with both he and his father later perishing in a gunfight with first responders.

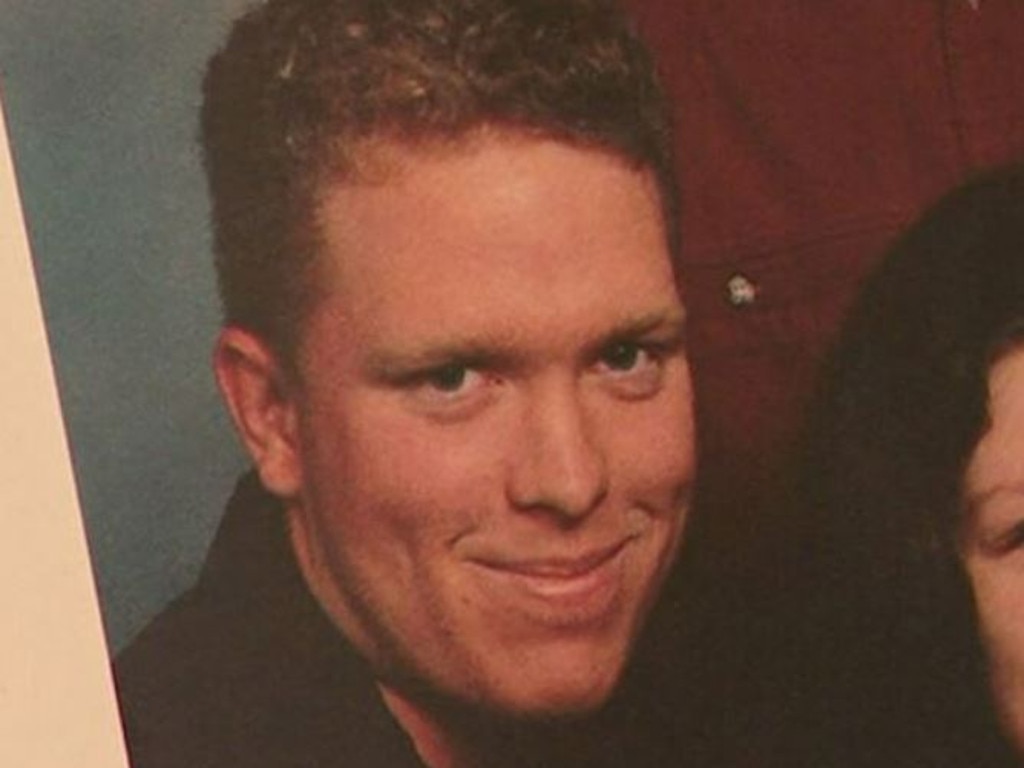

The same extremist views were held by Gareth Train before he, his brother Nathaniel and wife Stacey gunned down two police officers and an innocent neighbour during a routine missing person inquiry on a Queensland property on Monday afternoon.

Like the Kanes, the Trains – who have been described by Queensland Police as a “murdering, evil trio” – were also killed in the ensuing shootout with authorities.

Within hours of the news breaking, attention had turned to Gareth Train, who had been an active member of a number of conspiracy theory websites.

His bizarre beliefs included that the 1996 Port Arthur massacre was a “false flag operation”, that the government was running “re-education camps” and that Princess Diana’s death was a “blood sacrifice”, as well as an opposition to vaccines and Covid lockdowns and support for the sovereign citizen movement.

Deakin University terrorism expert Greg Barton told news.com.au that the Covid pandemic had been an “accelerant” for a string of dangerous conspiracies that had already existed, and that it had brought people with similar outlandish viewpoints together like never before.

“Most of the people who were drawn into anti-vax conspiracies were probably not from sovereign citizen groups, but the pandemic caused people who didn’t understand science, who were sceptical of the government, who didn’t like mandates and lockdowns and who were anxious about their employment to be linked with sovereign citizen types,” he said.

“It brought people together and accelerated things.”

Inside twisted movement

Prof Barton said the “grand conspiracy” behind the sovereign citizen movement was the idea the modern nation state is illegitimate, modern laws have an oppressive hold over the population and people need to “be brave and stand up to dictatorial governments and laws”.

“The way they make their case is by doing weird things like driving cars with number plates they’ve made up themselves, writing letters and strange correspondence with weird punctuation and using particular language they believe will somehow deliver them from having to pay tax or other prosecution cases, or driving without a registered vehicle,” he explained.

“On the surface it seems kind of silly, but underneath is a deeply held view that the state is illegal and people need to wake up from the grand conspiracy.

“It’s like The Matrix red pills – people need to wake up to what’s going on and resist.”

Prof Barton said some adherents in the US and in Australia had taken the concept so seriously they became recluses, living on isolated acreages off the grid – which bears a striking similarity to the case involving the Trains.

“They believe police have no right to be on their property … and they are prepared to use violence. There have been a number of cases in the US that have resulted in deadly gunfire and a loss of life,” he said.

“When the government does interfere in people’s lives, it’s usually in the form of a letter from the council or state government, but the sharp end of it is more likely a police officer turning up to ask questions and issue fines, and so uniformed police can be seen as the illegitimate agents of an illegitimate state.

“Because the idea of policing is the understanding that the state has the right to use violence as necessary to protect the greater good, there’s the perverse logic that because they are carrying firearms and wearing body armour and tasers, they are seen as agents of violence and appropriate targets of violence.”

Prof Barton said while they were two distinct movements, there were also often links between conspiracy theories such as the sovereign citizen movement and white supremacist and neo-Nazi themes.

“The majority of people don’t hold (these views) but those ideas have been linked to a lot of hateful language in America and it is creeping into Australia,” he said.

“It’s often the gateway to reinforce the idea of being under siege and it ups the emotional stakes. Some people are prepared to kill and die for a cause and once they go down that domain – we saw Brenton Tarrant in Christchurch firmly linked to that domain – people who do these kinds of things can then become heroes and be eulogised online, and inspire others to follow.”

Prof Barton said conspiracy theories tended to snowball, and at the extreme end, adherents can come to think of taking and losing life as “some sort of crowning achievement” instead of a failure.

He added that extremists wanted to generate as much attention as possible as they believed their “mission” was to “wake people up from ignorance and reveal the truth”.

“As the stories bounce around online it empowers these people, because most are losers with no influence and no authority – they’re not a person of any great power, but if they can get a Pauline Hanson or a Mark Latham to pay attention, they become part of a new story and have more power,” Prof Barton said.

“With these online communities, there’s a vast stock of material and once you read them and start down the rabbit hole – you might start with questioning vaccines, but you end up reading a lot of harmful material and form friendships with people who are a further down the rabbit hole who draw them in, so it’s a perfect storm of things that can spiral.

“The common link is a sense of hopelessness, alienation and despair, and the sense that it’s not a personal failure, it’s because you’re a victim, and not just randomly, because of a vast conspiracy so you should join the movement and fight back.”

Prof Barton said acts of violence carried out by extremists such as the Trains, as well as those involved in the January 6 Capitol riots and the recent plot by Germany’s Reichsbürger fringe group to overthrow the government, fitted the definition of terrorism as non-state actors using or threatening to use violence against symbolic targets in a bid to force change.

Australia’s scary ‘tipping point’

Alarmingly, Prof Barton said Australia and the wider world was now past the “tipping point”, with more than half of counter-terrorism measures now focused on battling far-right conspiracy ideologies.

He added that threats were likely to manifest as “lone acts” which could nevertheless be “of a very large scale of devastation”.

“We have bollards everywhere and we take care with public gatherings but we’re still vulnerable from a policing point of view,” he said.

“We do need to work on this and take it seriously. Unfortunately Queensland will start a whole new conversation about this in Australia. Christchurch brought home that it was no longer a potential problem, it’s an actual problem and now we’ve seen another manifestation, it will transform the way we live.

“In America, hundreds of police are killed a year because so many people are carrying weapons. It’s not the same in Australia but an increasing number of first responders, whether police or ambulance in uniform, will have to do extra risk assessment when out on normal business calls out of fear of ambush.

“It’s disturbing and escalating and results in so much harm.”

Prof Barton said we needed to act now to prevent future tragedies, starting with calling out hateful speech in public forums, in parliament and in the media.

“(Queensland) was a wake up call – we shouldn’t be paranoid and re-up the national terror threat, but we should take it seriously and change how we deal with bad behaviour … rather than closing our eyes and turning away,” he said.

“There’s a messy and complex entangling of social networks and the majority of people on the edges … are relatively harmless, but some will slip further down the rabbit hole and become dangerous, so it’s important not to use too broad a brush to tar people with, but to also recognise what’s at play here.”