What life was like for Aboriginal people during colonisation

IT HAS been described as a “good thing” for Aborigines, but a map shows what colonisation was really like for Australia’s first peoples.

MORE than 200 years after Captain Arthur Phillip first landed in Sydney Cove, debate is raging about whether we should commemorate a date called “Invasion Day” by some in the Aboriginal community.

Some Australians, like former prime minister Tony Abbott believe settlement was a “good thing” for the Aboriginal people, but others have slammed his ignorance.

So what was life like for Aboriginal people back in 1788?

AT FIRST THEY WERE ‘SHY’

There are no records revealing what the Aboriginal people thought of the strange men who came ashore at Sydney Cove on January 26.

The First Fleet actually arrived at Botany Bay on January 18 but decided to move to Sydney Cove about a week later because it had more fresh water and fertile soil.

The commander of the fleet, Captain Arthur Phillip dropped anchor at Port Jackson — the waters of Sydney’s natural harbour — on January 25 and the next day a camp was set up.

The first convicts, who were all male, arrived on January 26 and a British flag was erected. The women were brought in some time later.

It wasn’t until February 7 that an official ceremony was held establishing government over part of Australia and Capt Phillip was proclaimed as the governor of the new settlement.

Professor Ann McGrath, director of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, said the Aboriginal people greeted the settlers with spears raised but somehow Capt Phillip managed to signal he was coming in peace and didn’t want conflict.

“He described them as ‘shy’, not hostile,” Professor McGrath said.

Records of the early days of settlement published in the book The Settlement at Port Jackson by Watkin Tench, reveal the Aboriginal people avoided the newcomers.

“They seemed studiously to avoid us, either from fear, jealousy, or hatred,” Tench wrote.

“When they met with unarmed stragglers, they sometimes killed, and sometimes wounded them.”

Tench said he initially thought they had an evil nature but changed his mind after seeing several instances of their “humanity and generosity”.

He eventually concluded “that the unprovoked outrages committed upon them, by unprincipled individuals among us, caused the evils we had experienced”.

Governor Phillip tried to create a good relationship with the Aboriginal people and enforced laws against killing them.

“Philip considered himself a peacemaker and thought he could negotiate with the Aboriginal people,” Professor McGrath told news.com.au.

He kidnapped some Aboriginal men to try and gain information about food and water sources as well as their language. One of them was Bennelong, who eventually came to live among the first settlers and even travelled to England.

“During those early years it wasn’t all conflict and the Aborigines were very good at trying to negotiate a place in the new society.”

But the uneasy peace didn’t last.

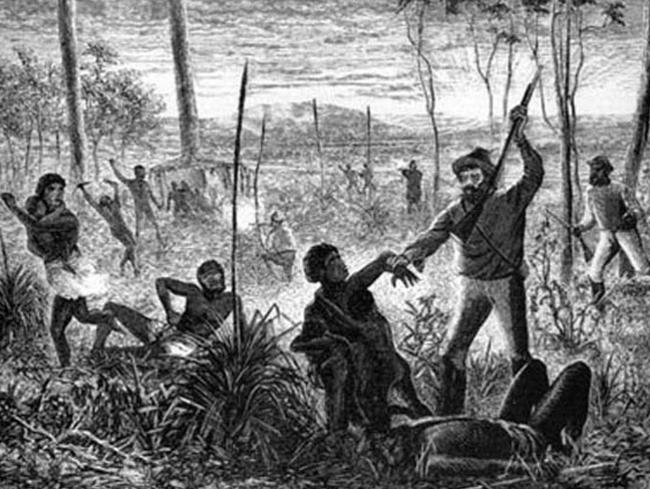

BAD BEHAVIOUR AND BLOODSHED

Even though the Aboriginal people generally tried to keep their distance from the settlement, they were sometimes targeted for their fishing-tackle, weapons and women.

Governor Phillip banned the sale of traditional tools to try and stop their goods being taken but this didn’t stop everyone.

In March 1789, 16 convicts left their work without permission, armed themselves with tools and large clubs and marched to Botany Bay to try and steal some of the Aboriginal spears and fishing equipment.

But the Aborigines must have seen them coming and attacked them, killing one man and injuring seven others. The governor ordered the men to be severely flogged.

Worse was to come.

“There was a lot of bloodshed as the colony spread, as they were dividing up land for agriculture,” Professor McGrath said.

“They were very ignorant in what they were doing, a lot of convicts went loose and stole spears and axes.

“They raped the women ... sexual violence led to a lot of conflict.

“There were a lot of massacres in Victoria and NSW.”

During the early years, the Governor tried to keep the convicts from going anywhere — they were technically supposed to be in a prison but some still managed to get out.

Later squatters were authorised to create settlements away from policing, so they got away with a lot.

“It wasn’t legal to kill Aboriginal people so that happened covertly,” Professor McGrath said.

It wasn’t long before “frontier violence” became widespread, with Aborigines killed in massacres, including women and children, some of who were driven off cliffs. Other tactics included disease, starvation and the poisoning of food rations.

The word “dispersal” was soon being used as a euphemism to describe the killing of Aboriginal people.

As the settlers finally found a way through the Blue Mountains, the influx of British put a strain on traditional food sources and destroyed sacred sites.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who favoured a cautious and slow approach to settlement, was replaced by Governor Thomas Brisbane who changed laws that led to a flood of land grants across the mountains.

The Aboriginal people began guerrilla-warfare style attacks on stations, which were crushed when martial law was proclaimed in 1824.

“This was significant as it pretty much meant war,” Professor McGrath said.

Soldiers were dispatched to deal with the situation and began murdering the population.

Gradually diseases like smallpox and unauthorised massacres began wiping out the population.

By the 1830s, the murder of Aboriginal people by British colonial stockmen, settlers and convicts was generally accepted, despite laws against it. The violence was so bad, a police magistrate at the time even described it as “a war of extermination”.

One act of violence actually happened on what’s now known as Australia Day — January 26, 1838. A commandant of the NSW Mounted Police and his men massacred up to 50 Aboriginal people in retaliation for the killing of stockmen.

They also encouraged nearby stockmen and settlers to murder any Aboriginal people they saw.

But authorities did try and crack down on unlawful killing, with seven men publicly hanged in 1838 for killing at least 28 Aboriginal people.

Despite this, the brutality continued for many years, with some Australians protesting at the indiscriminate killing of the Aboriginal people, which in some areas was attributed to “the brutality of the Native Police and some of the settlers, who, in the beginning, relentlessly hunted down and shot as many of the males of the tribe as possible”.

Professor Lyndall Ryan at the University of Newcastle is mapping massacres against the Aboriginal people, which she has defined as the indiscriminate killing of six or more undefended people.

So far she has identified more than 170 massacres of Aboriginal people in Eastern Australia and six recorded massacres of colonists between 1794 and 1872.

Massacres of Aboriginal people were typically carried out by hunting parties of soldiers, armed settlers, mounted police and/or native police.

Research found they were usually planned acts of violence in retaliation for an Aborigine killing a white person — usually a man who had abducted and sexually abused an Aboriginal woman — or because an Aborigine stole property such as livestock left on their hunting grounds.

Professor Ryan’s research has found many major massacres happened alongside rivers.

“That’s where the majority of Aboriginal people were, that was where the good pastoral land was and that’s where the settlers wanted to be,” Prof Ryan told ABC.