Australian political historian says the past holds major lessons for Voice to Parliament

The past tells us a lot about referendums and, if history repeats, we could be back at the ballot box in no time should Voice to Parliament fail.

When it comes to the Voice to Parliament referendum, it seems history may tell us a lot.

We have learnt from time gone by that Australians don’t often know much about what they’re voting for, they sure as hell don’t want the government to have more power, and it’s not unusual for prime ministers to give failed referendums a second go.

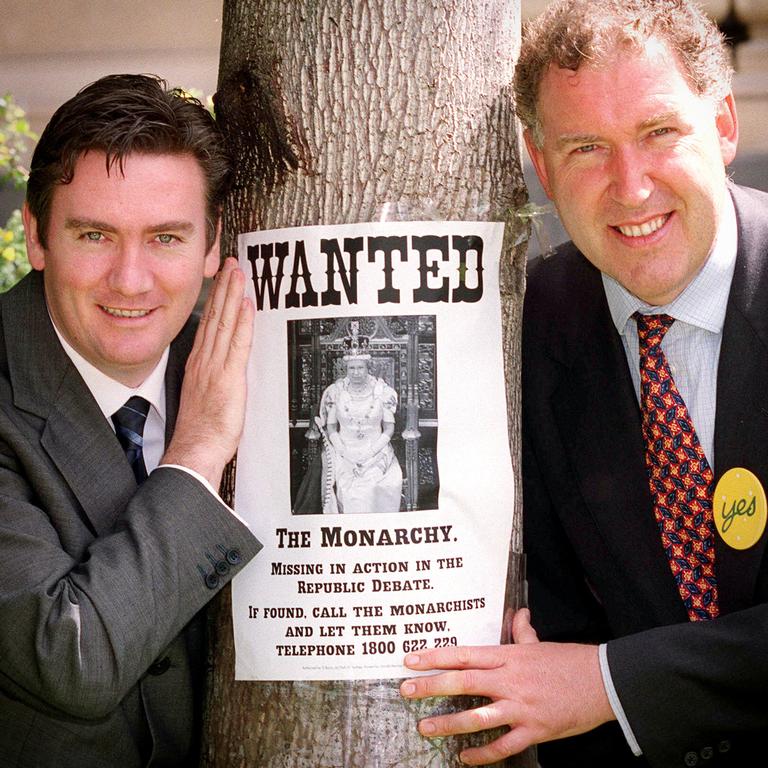

The Voice to Parliament referendum will mark the first time Australians have voted in a national referendum since 1999, when we turned down becoming a republic, meaning no Australians under 42 have ever been polled on changing the constitution.

Dr Benjamin Jones, a historian and senior lecturer at Central Queensland University who specialises in Australian politics, says how Australia perceives constitutional change may have been skewed because of the break between ballots.

“It probably has had an impact in that the voting public isn’t as used to the process of having referendums,” Dr Jones told news.com.au.

“There was at least one every decade throughout the 20th century, and I think having them regularly gives the impression that while it’s important, it’s also a safe thing to do – it’s a regular part of constitutional maintenance.”

The quarter-century gap between referendums, Dr Jones argues, gives Australians the impression that October 14 is “incredibly consequential” and a “once in a lifetime” moment.

“It creates an aura around the constitution, the idea that it should never be changed,” he said.

“When referendums take place regularly, people are more accustomed to the idea that ‘yes, it’s an important document and it shouldn’t be changed frivolously, but changing it regularly is just part of the modernising process’.”

Only eight referendum questions of 44 proposed in Australia’s history have achieved the double majority to pass.

Dr Jones suggests this is more of a problem with the “Section 128” mechanism than the proposals.

Section 128 of the Constitution dictates for a referendum to be successful and passed in Australia, the majority of voters in a majority of states must say yes, and the national majority of voters must also vote in favour of it.

“I think (the pass rate) shows a flaw in the mechanism because it does lend itself to partisanship,” Dr Jones told news.com.au.

“It does allow these proposals to be seen in the light of a Liberal or Labor proposal.

“The intention behind 128, ironically, is that it was meant to be a circuit-breaker because the parties might not be able to agree on something, but a commonsense solution could be found if it’s thrown to the people.”

Australia’s constitutional knowledge is meagre, according to Dr Jones, and that has historically had different impacts on Yes and No campaigns.

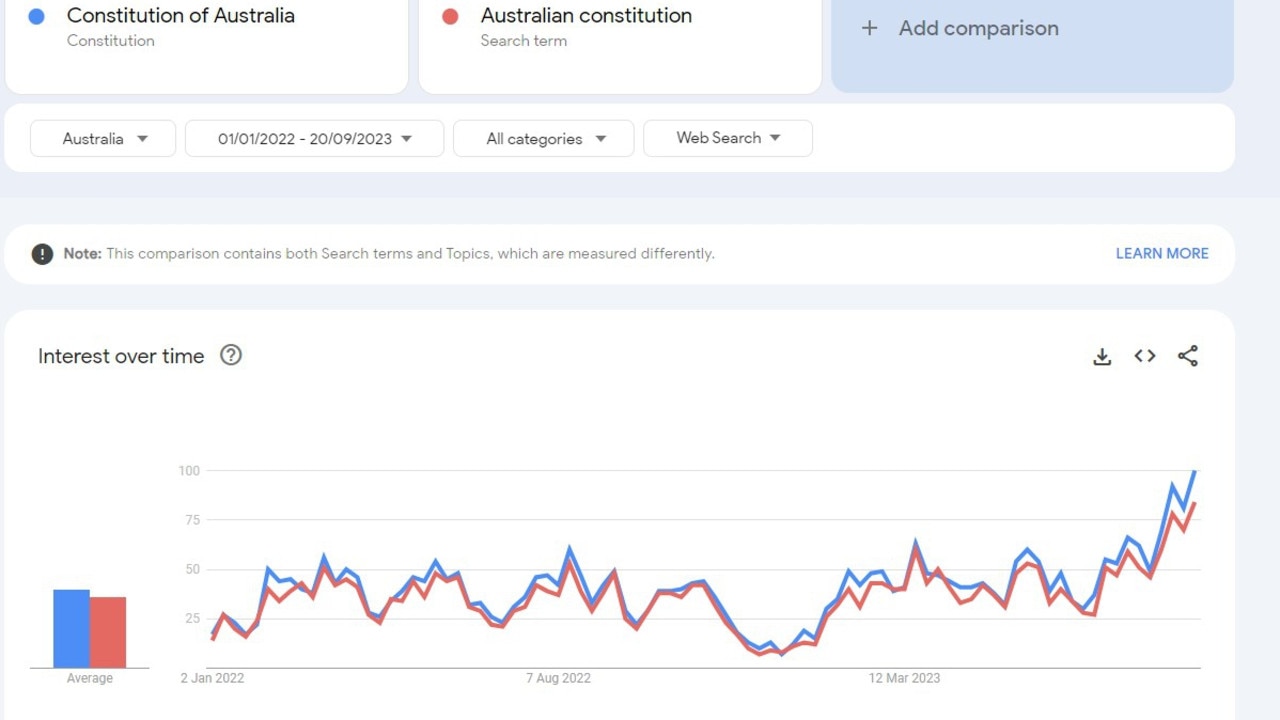

In fact, Google data shows a significant increase in searches for the terms “Constitution of Australia” and “Australian Constitution” between January 1, 2022, and today – suggesting some last-minute reading up.

“It’s not something that’s taught very deeply or effectively in schools, and so a lot of people’s starting point is actually, ‘what does the constitution even do?’” Dr Jones said.

“That makes any Yes case more difficult because their first step is actually explaining what the constitution currently says and what they would like to amend it to.

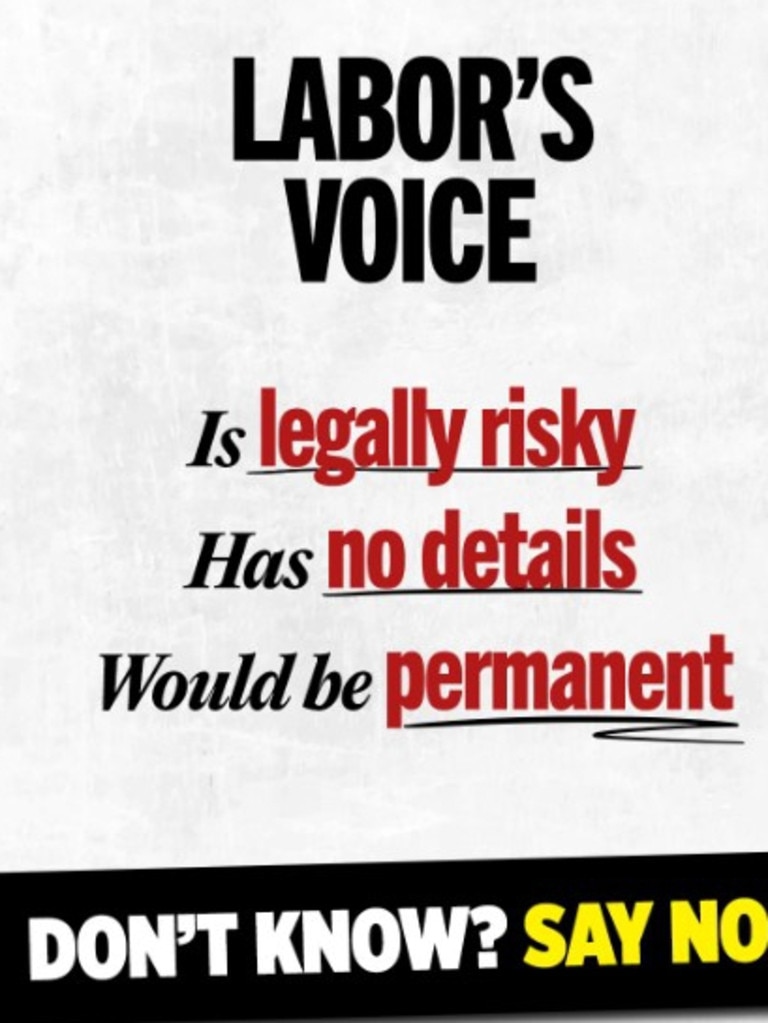

“People who don’t want to have those conversations are likely to default to a no.

“There are still a lot of Australians who are only vaguely aware of what the constitution is, and those are the ones most likely to vote no – not because they necessarily oppose it, but because they don’t necessarily understand what’s being proposed.

“And I suppose that’s why the No team also uses slogans like ‘don’t know vote no’.”

In a recent article in The Conversation, Dr Jones pointed out several significant lessons Australians could learn from past referendums.

One that holds poignancy and perhaps a mirror to October’s Voice referendum is that Australians historically don’t want the government to have any more power.

“The first lesson is that Australians are trenchantly opposed to any change that increases the power of the federal government,” Dr Jones wrote.

“Between 1906 and 1999, there were 23 proposals that would have extended the power of the Commonwealth. Only two were successful (in 1946 and 1967), and both were dealing with extraordinary circumstances in post-war reconstruction and removing discriminatory references to Indigenous people.

Historically, this is a standard No tactic. Referendum in 1999 was called the politician's republic, 1988 was attacked for giving more power to Canberra. In this case, however, it is obviously untrue. The Voice didn't start in Canberra, it's literally in the name #UluruStatementhttps://t.co/rJD1C0fwr2

— Benjamin T. Jones (@DrBenjaminJones) April 6, 2023

“A fair conclusion to be drawn is that the electorate is broadly happy with the division of power between the states and the Commonwealth.”

His article also pointed out the astounding fact that every Labor prime minister who oversaw a failed referendum — besides John Curtin, who died in office — had a second attempt.

Bob Hawke, Gough Whitlam, Ben Chifley, and Andrew Fisher all oversaw two referendum attempts each.

“If Voice does go down, having already expended a great deal of political capital in constitutional change, (Anthony) Albanese may well follow this long tradition,” he wrote.

Coupled with a recent, albeit half-hearted, commitment from opposition leader Peter Dutton also to hold a referendum to recognise Indigenous Australians constitutionally – it would appear Aussies could expect to head to the ballot box again in the not-to-distant future if polling comes to fruition and Voice fails.

However, Dr Jones told news.com.au he was not in the business of making predictions.

“I study the past,” he laughed. “All I’m saying is that there hasn’t been a Labor prime minister who has gone through all that effort of putting up a referendum who has thought it’s not worth trying again.

More Coverage

“There’s an X factor with Albanese though, especially with the passing of the Queen.

“Had Voice not already been set in place for a referendum – I think we’d likely be discussing the possibility of a republic.

“If Albanese does take a second to vote, later on, it might not even be on the same topic.”