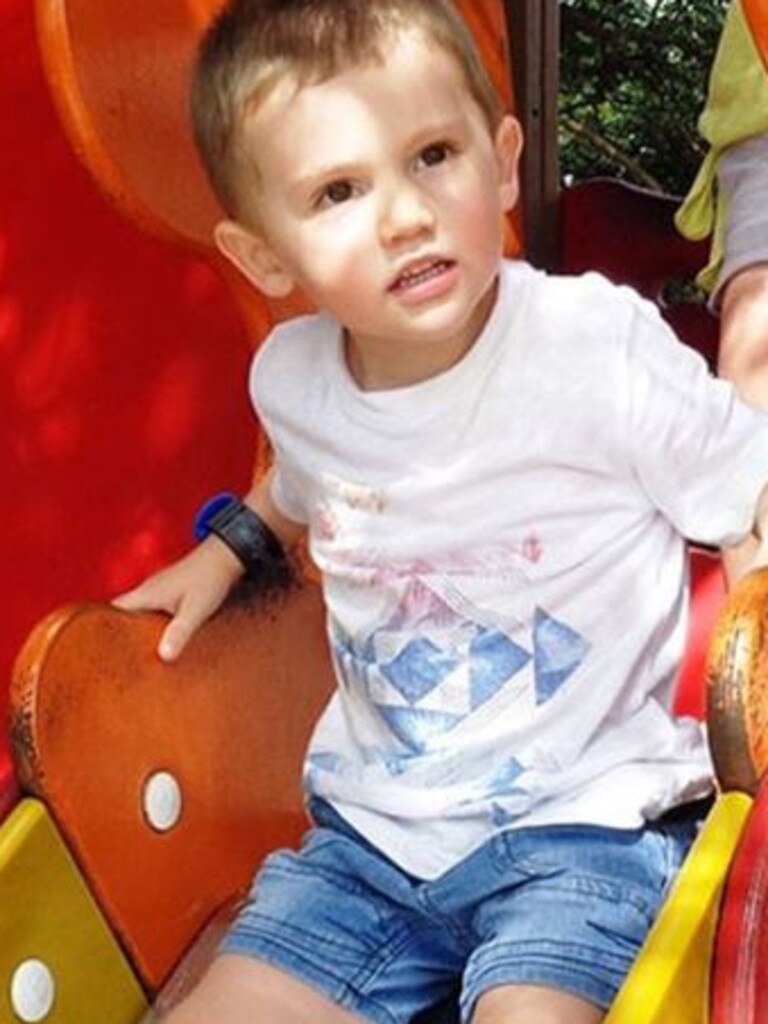

William Tyrrell’s inquest starts in Sydney

The inquest into William Tyrrell’s disappearance has heard from his foster mother, who broke down as she recalled the day he disappeared.

William Tyrrell’s foster mother broke down while describing the frantic moments after William vanished and she desperately searched for him in his Spider Man suit.

Crying as she recalled the seconds as she raced about the yard looking among the ferns and trees, she said, “he wouldn’t do it”.

“He wouldn’t hide, he’s not brave enough.

“I raced around the house, opened every single cupboard, every wardrobe.

“I go through everything.

“I went out, down through all these ferns, he’s not there.

“I am just trying to find this red.

“I think in all this green, I’ve got to see some red somewhere.

“Where’s the red? Why can’t I see the red?”

She also remembered two strange cars in the street before his kidnap that she later believed were there to abduct both him and his sister.

“My heart just sank because I thought those two cars were there for both of them,” she told the court, her voice breaking as she wept in the witness box.

The foster mother, who cannot be identified, said she first saw the two cars when she opened the screen doors and drew back the curtains early on the morning of the day William vanished.

Dressed in a cream wool wrap, her straight brown hair cut to the shoulder, for the most part she gave her evidence clearly in a soft well-modulated voice.

She also told the court that William and his sister had visited the location where he was kidnapped several times, were known to neighbours and had attended a street party there at Christmas time.

After her father died in February 2014, the family had travelled to Bali, where they bought William’s Spider-Man suit.

Then they returned to Kendall, arriving the day before William’s disappearance.

Each trip to Kendall and overseas had to be done with the permission of the Salvation Army home care group which supervised William’s care at both his foster home and with his biological parents.

The foster parents had arrived at 9pm on September 11, 2014 put the kids to bed, and she had discussed the fact that her mother’s washing machine needed fixing.

The next morning after 7am, the foster mother saw two cars opposite her on Benaroon Drive, Kendall and immediately thought “that’s odd”.

The white and gunmetal grey cars were “really old, really dirty … with missing hub caps” and “tinted windows”, were parked one in front of the other near a telegraph pole, and between two different driveways.

The reason they looked “weird” was because the large, one acre blocks on the street “all had long driveways, so if you were visiting someone you’d drive up to the house, not walk from the street.

The foster mother also became upset when she was describing another car in the street that morning driven by a “thick-necked” man with a weathered face who had given her a challenging stare.

“You know when you look at someone and there’s that second challenge, ‘why are you watching me, I am watching you’.

“It was fleeting.”

The foster mother said that the police had since identified the car.

“I did have pretty intense reaction,” she said, her voice breaking.

“But in terms of the person … the image we ended up with is not the man.”

She described the man as large, with a big abdomen, short red hair, “not overly tanned” and having no facial hair.

“He was a big man,” she said.

She had noticed him when her daughter ws bike riding in the front driveway and said, “who’s that car Mummy?”.

The foster mother agreed with counsel assisting the inquest, Gerard Craddock, SC, that in statements immediately after William’s disappearance she had not mentioned the first two cars she had seen.

Nor had she initially mentioned the large man driving in an old “LTD’ style vehicle about whom she said, “I have seen him and he’s seen me”.

“With William missing it went right out of my mind,” she told the court.

“But six days later, I just had this flash that there were two cars.

There were a number of people who were saying to me, ‘you will remember things when you least expect it’.

“The brain is a really weird thing. It will recollect things when you least expect it.”

She said on the morning of September 12, 2014, her husband had become “frustrated” with the children being noisy.

“I remember saying ‘you just take care of yourself and I will take care of them’.”

After her husband drove off to the chemist and attended a telephone conference call at a spot were there was better phone reception, she went outside with William.

She said playing a chasing game called “mummy monster” with William in the yard, when she glanced back and saw the same two cars she had seen first thing in the morning.

No-one was inside the cars, but one had its driver’s side window down and she noticed more detail about the vehicles.

The white car had “aged white paint … what stuck out for me about the cars was I thought they’re really old, really dirty and missing hub caps.

“They were just out of place.”

She said the large man she had seen in the LTD style car had driven up Benaroon Drive and turned his car around in the neighbour’s driveway before exchanging a look with her.

Asked why she hadn’t mentioned the man in an earlier statement, she said, “I don’t why I said that.

“Things come back to you in those moments of clarity.

“I’m firm on that. I saw that man. That car was there.”

She said she was still working with police on an image of the person she saw, although at the time she had told her daughter it was “probably a neighbour”.

POLICE HAVEN’T RULED OUT ABDUCTION FROM RELATIVE

Police have not ruled out that William Tyrrell could have been abducted by a relative or associate, the inquest into the missing boy has heard.

But police have established his biological parents were both in Sydney on the day he vanished at Kendall in northern NSW on September 12, 2014.

“Investigators have not drawn the conclusion that no relative or associate was involved in William’s disappearance,” Counsel assisting the inquest Gerard Craddock, SC, told the hearing.

“After the disappearance, police acted very swiftly to find the (biological) parents.

“There is no doubt both were in Sydney … on the 12th.”

Mr Craddock told the court that before William was taken from his birth parents into foster care the Department of Family and Community Services officers arrived to collect him and found he was gone.

That was on February 8, 2012, and a warrant was issued for the arrest of William’s birth mother.

“William was located by the NSW Police with his parents … at a relative’s house on 15 March 2012,” Mr Craddock told the court.

William was taken into the care of the FACS minister and given to the foster parents he was living with at the time of his disappearance.

On the morning William went missing, the inquest heard, William’s foster mother spotted two “aged and unkempt” cars parked closely together across the road from 48 Benaroon Drive in Kendall.

The foster mother saw the cars twice, which in the remote street where her mother — William foster grandmother — lived, was an unusual sight.

The house where the foster grandmother was visiting with her daughter and William was like all other houses on Benaroon Drive, set on large blocks where visiting cars usually parked off the street.

And that part of Kendall was a “sleepy village”.

Mr Craddock gave a dramatic account of how the morning William disappeared unfolded.

He said William’s foster parents had decided to go up to Kendall to stay with her mother a day earlier than planned.

The foster father had a telephone conference meeting that required “a bit of quiet and a decent internet connection”, and that would be difficult driving with “children in the back”.

After arriving on September 11, 2014, the following morning William and his sister woke early around “six or seven … excited to see Nanna”.

Although William had worn his favourite Spider-Man suit several times, it was the first time he would be wearing it in Kendall.

The last photograph taken of William, at 9.37am on the day he vanished, shows him dressed in the suit “roaring” like a tiger, Mr Craddock said.

The foster mother saw the two cars parked close to one another in the street just before her husband drove off to have medical prescription filled at the chemist and his conference call meeting in a place where he could get internet reception.

On the way home, he sent a text message to his wife via Siri.

At the house, William and his sister were enjoying playing and drawing on the back veranda, and riding their bikes in the driveway.

The foster mother “took William for a walk among … trees between the house and 30 Benaroon Drive”.

She tried to get William to climb a tree with low branches, but “William thought it was too high” and he got back down on the ground.

At this point, the foster mother again saw the old parked cars across the road.

She also has “a distinct recollection” of seeing another car drive up to 52 Benaroon Drive, then reverse and disappear, Mr Craddock said.

The time was “close to 10.30am. William was playing a game pretending to be a daddy tiger.

“William was ducking to the northeast corner of the house and then rushing out and roaring at the ladies,” he said.

“They were drinking tea.”

The foster grandmother had “thought William was being very boisterous and loud”, but the foster mother had replied “he’s a boy, that’s just how they are”.

Minutes later, the foster mother “had just finished her tea and … she noticed it had “become quiet, too quiet”.

“There had been one loud roar and then nothing,” Mr Craddock said.

She called for William, but there was “no response”, and she went looking up Benaroon Drive for his red Spider-Man suit among the green foliage up and down the street.

When her husband arrived home, she asked him: “Is William with you? I can’t find him.”

A video of a walk-through by police with the foster father in the yard around the house where William went missing was played in court.

He can be seen showing the detective various fences that he thought William could have got through and others that he couldn’t have.

“He does know his limitations,” the foster father says in the video.

“He could walk straight under here,” he says at a low fence.

But at a higher fence, says “he’s not going to get under this, it’s too hard … he’s not a wanderer”.

The foster mother went out along the street and neighbour Anne Maree Sharpley came out to help search.

At one point Ms Sharpley hugged the crying foster mother, saying “breathe, it’s okay, we will find him”.

Ms Sharpley saw the foster father “running around the bush calling out ‘William’ … ‘he looked scared, lost, worried’”.

At 10.56am, the foster mother dialled triple-0.

The call, which was played in the court, begins with the foster mother saying, “my son, he’s missing, he’s three-and-a-half”.

She then says, “we have been looking for him for about fifteen or twenty minutes” and gives a physical description of him, including that he has “a freckle on the top of his head if you part it at the side”.

She tells the triple-0 responded “it’s the first time” William has run off.

Mr Craddock told the court that statistically, according to US research, “74 per cent of children abducted and murdered by a stranger … (are dead) within three hours”.

But he said “it hasn’t been determined … that William has been abducted by a stranger, that William has been dead or has been murdered”.

He said missing children are not usually reported to police for about two hours.

But in the case of William, he was reported missing after about 20 minutes and the first policeman arrived on the scene by 11.06am.

By 12.30am, more police had arrived with search dogs, and drains, dams and waterways were being searched.

Mr Craddock said despite the fact the inquest was investigating the “suspected death” of William, “there’s no establishing that William is in fact dead”.

He said it also had “not been established that William has been abducted by a stranger … or is deceased”.

“If it is the case that William was abducted … it means a person snatched a three-year-old from the safety of a backyard and that person remains in our community,” Mr Craddock told the court.

“Police suspected abduction early on.”

The court also heard from FACS senior practitioner Catherine Alexander that William’s case file did not record any “open animosity” between Williams biological and foster parents during visits.

Ms Alexander said that “if there was animosity … we would want it written down”.

Former Salvation Army home care supervisor Benjamin Atwood was also asked by Mr Craddock if he had observed in animosity and he said he had “no recollection” of any.

Earlier, William’s biological father wept in court as the inquest into his missing son opened.

The father, who cannot be named, wept as he sat with his half-brother’s arm around his shoulders in the courtroom.

Missing William’s biological grandmother also wept as she heard Counsel Assisting the inquest, Gerard Craddock, SC describe the events of the morning William went missing.

The biological and the foster families of William Tyrrell sat on opposite sides of the court which was also packed with supporters for both sides.

NSW Deputy State Coroner Harriet Grahame welcomed William Tyrrell’s families and friends to the court, acknowledging that losing a child “must be one of the greatest pains of all”.

On one side of the courtroom, the foster parents — who cannot be identified — sat after being accompanied into court by NSW Police Minister Troy Grant.

They looked grim as they heard the triple-0 call made by the foster mother played in court, and details of the search for William as it became obvious he was nowhere in sight.

The foster parents were with William at his foster grandmother’s house on the morning the three-year-old vanished from the NSW Mid North Coast town of Kendall on September 12, 2014.

William’s biological mother is due to give evidence later this week.

Paul Savage, the neighbour who helped in the search for William, is also due to give evidence.

William’s disappearance sparked one of NSW’s biggest manhunts for a missing child.

Strike Force Rosann was set up to investigate, but no trace of the boy has ever been found.

Deputy State Coroner Harriet Grahame will conduct the inquest at the Forensic Medicine and Coroner’s Court Complex at Lidcombe, in western Sydney.

A massive brief of evidence, containing at least 15,000 items, will go before Ms Grahame.

The first of two weeks of hearings will explore William’s foster and biological families, the period of time around the disappearance and early parts of the investigation.

And, according to The Sun Herald and the Sunday Age, the inquest will focus on a new person of interest — a man who has never been publicly discussed by detectives.

Throughout the investigation, William was referred to “a little boy lost” but police soon came to suspect something more sinister happened and zeroed in on known paedophiles and criminals from nearby holiday towns.

But no one has been charged for the suspected abduction.

It is understood investigators hope the first week of hearings will show William did not wander into nearby bushland but was, instead, snatched by a predator.

In mid-2018 they conducted a large-scale search of bushland near the Kendall home to rule out misadventure and firm up their theory.

The closely-guarded persons of interest list, which ballooned to include hundreds of names over the years, has been whittled down for the inquest’s second sitting in August.

Some names on that list have been previously released by police but sources say one so-far unidentified person will be watched closely when they are called in front of the inquest.

Counsel assisting Gerard Craddock SC will deliver his opening address at 10am on Monday.