Fiery exchange as Tyrrell inquest draws to an end

A woman who heard a startling sound after William Tyrrell disappeared had a fiery exchange with her paedophile neighbour at the toddler’s inquest.

Dramatic scenes erupted in court on the penultimate day of the William Tyrrell inquest as a woman who heard a child’s scream from the bush the day after the boy disappeared told her paedophile neighbour “You know something”.

William was wearing a Spider-Man suit and pretending to be a tiger when he disappeared from his foster grandmother’s home on Benaroon Drive in the quiet northern NSW town of Kendall six years ago.

An inquest has been underway since March 2019 before deputy state coroner Harriet Grahame, who is tasked with unravelling the mystery of what happened to William on September 12, 2014.

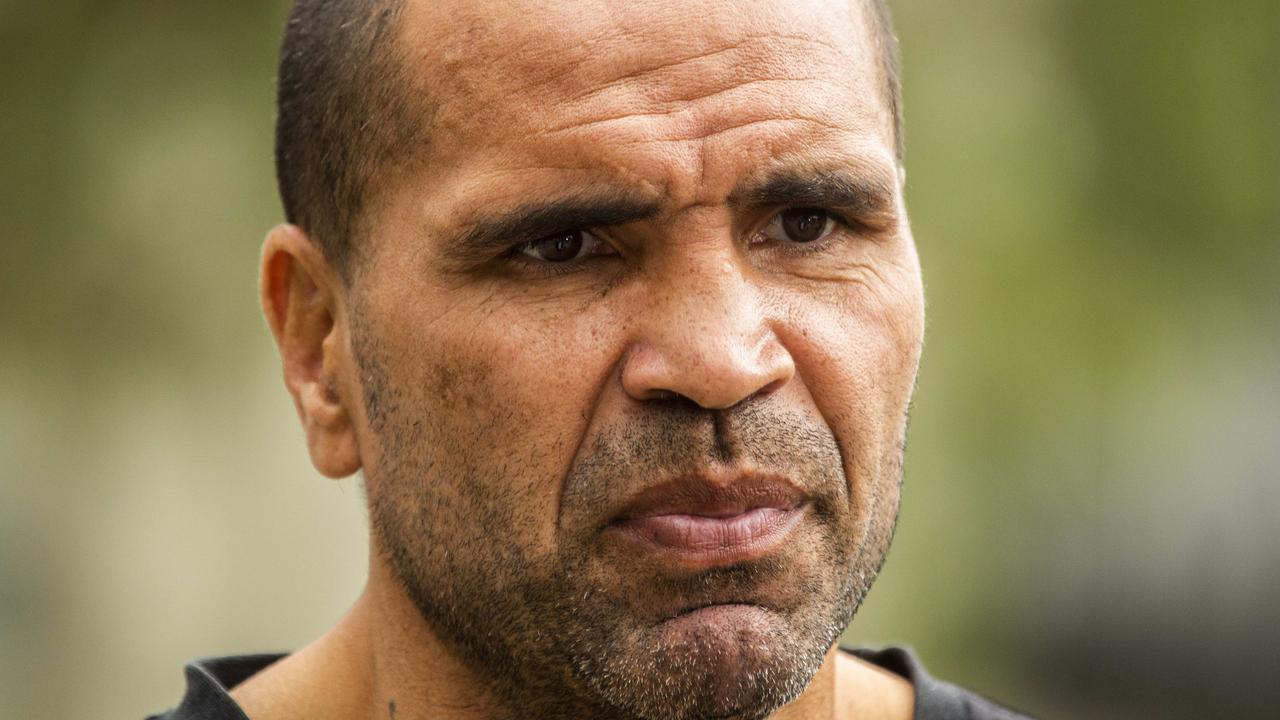

Convicted paedophile Frank Abbott, who lived in northern NSW before he was jailed for child sex offences, has been representing himself at the inquest from prison.

On Wednesday, he confronted his former neighbour, Anna Baker, over her evidence that she had heard a child scream in the bush the day after William went missing.

The skirmish played out remotely in the Lidcombe courtroom as Abbott, appearing over video, questioned Baker, who had phoned into court to face his follow-up questions.

She told the inquest on Tuesday she was tending to her strawberries when she heard the scream and immediately stood straight up, believing it was a male child.

But she did not think it was related to William, and did not tell the police until 2018 when a friend told her Abbott was living just across the paddock.

The exchange became tense as Abbott suggested she could not have heard a scream coming from his place.

“I heard the noise coming from the bush. Not your place,” she said.

“You’re the only person close to that bush. And you’re a paedophile.

“You know something, Frank Abbott.”

When Abbott protested he wanted to find William, saying “I’m in the same boat as you”, Ms Baker shot back, “I’m not in your boat mate”.

The massive police investigation had 26 investigators at its height, but that number has now dwindled to five, Detective Chief Inspector David Laidlaw told the court.

There are also two intelligence analysts working the case, making a team of seven.

“Have you given up?” counsel assisting Gerard Craddock asked him.

“No,” the inspector replied. “We never will.”

He confirmed police had not excluded anyone from the investigation, including William’s mother, father, foster parents and several high profile persons of interest.

“We haven’t closed the door on anybody,” he said, later adding “We’d be remiss if we did”.

Dr Helen Paterson, a memory expert and lecturer in forensic psychology at the University of Sydney, told the inquest:“Our memories are not perfect … we don’t remember things like video cameras,” she said.

“Many people think memories are reproductions of what we saw. But every time we recall an event we reconstruct it.”

She examined two pieces of potentially crucial eyewitness evidence, including from William’s foster mother who told the inquest two unfamiliar sedans had been parked on the quiet, rural street the morning William disappeared.

The woman initially told police she had not seen any suspicious cars but remembered them two days later, insisting to police the picture was “burnt into my brain”.

It has not been corroborated by other witnesses.

Dr Paterson said on Wednesday: “I can’t say if it’s a genuine memory or a false memory. I can say that it is possibly a false memory.”

She offered several possibilities: The foster mother could have genuinely seen the cars that morning, she could have seen them on a different day, or a leading question or photograph could have planted the notion in her mind, generating a false memory.

Dr Paterson said confidence was not always a good indicator of accuracy, and sometimes people who were very sure of a memory and often repeated it to others could have a “confidence inflation” effect over time.

She said this effect appeared to be present in the testimony of Kendall man Ron Chapman, who said he saw two cars drive past his house erratically that morning in 2014.

The first car was driven by a woman and William Tyrrell was standing unrestrained in the back seat, dressed in his Spider-Man suit, Mr Chapman told the inquest last year.

“Originally, he wasn’t very confident at all,” Dr Paterson said.

“He wasn’t sure if it was a dream or whatever and he became more confident over time that he had seen William Tyrrell in the vehicle that went past.”

Mr Chapman had relied on “script” memory – or what typically happens – in his interview, she said, noting he had misremembered his relatives had been in town and it had not been an ordinary day.

Dr Paterson assumed for her report that neither Mr Chapman nor the foster mother were lying, and each was trying their best to give an honest account.

Broadly speaking, humans were very bad at telling if people were lying, particularly based on their demeanour, Dr Paterson said.

She told the court it was possible to experience “inattentional blindness” in which you do not notice and cannot recall something that happens right in front of you.

This has been measured by experiments, she said, the most famous involving a person who is asked to watch a video and focus on three people in white shirts passing a ball to each other.

A person focused on the task tended to miss a “very obvious” person in a gorilla suit who walks into the middle of the game and beats his chest, she said.

The court will hear statements prepared by William’s family and his foster parents on Thursday.