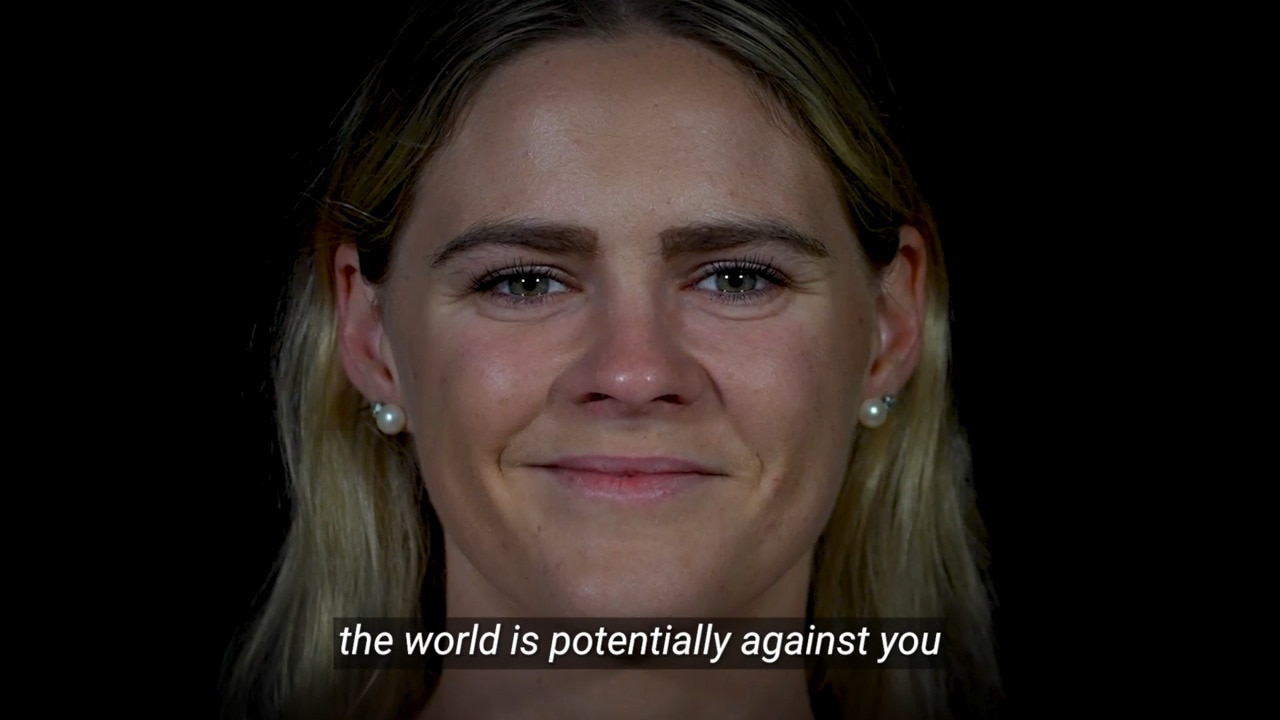

Maria Ruberto details how to raise a resilient child

Psychologist Maria Ruberto has not seen the resilience levels of children so low in her 31-year career. She is warning that we risk raising a generation with an array of mental and physical health issues if parents don’t take urgent action.

It’s a question uniting parents around Australia and the world amid a mental health emergency in young people.

How do we help our children become more resilient?

The figures tell a grim story about what’s been dubbed the “anxious generation”.

One in seven Australians aged four to 17 suffered a mental illness in the 12 months to

April 2024.

And mental disorders in 16 to 24-year-olds soared from 26 per cent to 39 per cent between 2007 and 2020-2022, an Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report found.

The pandemic, social media, overprotective parenting and too much screen time are among the factors being blamed for what The Lancet medical journal has called “a dangerous phase” for our youth.

Psychologist Maria Ruberto has not seen the resilience levels of children so low in her 31-year career across government, not-for-profit and private sectors.

Even kindergarten children are now presenting with psychological distress and anxiety.

She is warning that we risk raising a generation with an array of mental and physical health issues if parents don’t take urgent action.

“What we are seeing is a serious lack of emotional competence in children, and a lack of ability to problem-solve for themselves,” said Ms Ruberto, a member of Medibank’s mental health reference group.

“This is leading to some serious issues in schools.

“It can be kids not wanting to do particular things, having meltdowns, crying easily, and yelling and screaming more quickly as they can’t hold these emotions.

“We’re seeing a delay in responding to instruction, apprehension in children wanting to work with or talk to other children.

“Some children are becoming really quiet as they internalise their feelings.”

While there’s no easy fix, she said there were a range of strategies to help boost resilience in children.

But she’s concerned families were becoming less likely to stick to treatment plans designed to address emerging mental health issues in children.

“What we are starting to see with some of the families that we work with is a treatment resistance,” she said.

“Parents are busy working, and spending more time away from parenting and kids.

“Social media, screens and devices have a really big part to play.

“The treatment plans that we would put together for some of our families simply are not being adhered to.

“But mental fitness requires repetition.

“We need to stop, we need to be present and we have to reduce our distractions.”

Like many experts, Ms Ruberto feared a lack of optimism amid wars, global instability

and political upheaval — and viewing life events through a “pessimism tunnel” — was

filtering down to our children.

New research by News Corp Australia’s Growth Distillery with Medibank shows that 70 per cent of Australians believe that society is becoming less resilient amid growing concerns about our collective ability to handle stress and adversity.

“I think, as a society, we are eroding our capacity to be optimised,” Ms Ruberto, the founder of Melbourne’s Salutegenics Psychology, said.

“This is impacting mental and physical illness.

“There’s a rise in obesity, diabetes, asthma … and all sorts of pro-inflammatory diseases that come out of bodies that remain in heightened psychological distress.”

Ms Ruberto said there were a range of strategies to protect children from mental health issues, from healthy diets and physical activity, to teaching them how to manage their emotions.

One of the elements in building resilience was the development of the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for important cognitive functions such as decision-making and managing emotions.

She said it was critical well-meaning parents refrain from shielding their children from challenging situations or struggles, as it “robs” them of their ability to problem solve.

“We are seeing parents own a child’s distress because they are so incensed by what has occurred, but it’s taking away from allowing the child to learn and problem solve,” she said.

“And there is a massive cost to that.

“If you ask any parent ‘What do you want for your child?’ they will say, ‘I want my child

to be successful’.

“Well, if you want your child to experience success, your child has to experience struggle.”

Mindfulness expert and Monash University Professor Craig Hassed described a “perfect

storm” of factors that were causing a “pandemic of mental ill-health in our youth”.

Prof Hassed called for effective mindfulness programs education in every school, to train children in positive skills such as self-awareness, emotional regulation, compassion and communication.

“All of these things are trainable, but it has to be done properly or you risk making matters worse,” he said.

“When you start running a mindfulness program and you encourage them to start noticing more of what’s going on in their own minds and emotions and bodies, they start to actually realise that when they feel uncomfortable, they just dive for the phone and start scrolling.

“These kinds of behaviours are really handicapping kids.”

He said the issues had been building for years and now was the time to turn the tide.

“The greatest potential for turning this situation around will be when we seriously invest

in addressing the underlying causes rather than just trying to mitigate the effects,” he said.

Tips for building mental fitness in children

Move your whole body: At least 40 minutes of strong movement daily, such as climbing on equipment, running, swimming, hockey, basketball or netball, for healthy bodies and minds.

Get outdoors: Sunlight is important for immune health and setting our circadian rhythms, which helps children sleep better and allows the brain to commit learning to memory. Time outdoors can be as simple as playing with the dog, or helping with the gardening.

Brain food: A healthy diet full of clean, nutritious food and brightly-coloured fruit and vegetables not only helps our bodies fight physical illness but fuels the brain.

Playground rules: Teach children how to socialise and build positive relationships. Kids need instruction on setting boundaries and making friends, such as basic introductions and asking “Can I play with you?”.

Don’t step in too soon: If parents immediately intervene in a challenging situation, children can’t learn to properly develop problem-solving skills. They also miss out on the dopamine hit from working through an incident. Let them sit in an unpleasant state and then deploy the 5:3 rule.

More Coverage

The 5:3 rule: When your child is distressed, ask them five questions about what happened. They can be who, what, where, when, and how do you manage it. But don’t ask why, as it invites an emotional story. Let them talk for three minutes about the facts without saying anything, then ask them what they might need to do. Allow them to own the problem-solving process.

Source: Maria Ruberto, Salutegenics Psychology

Can We Talk? is a News Corp awareness campaign, in partnership with Medibank, helping Australian families better tackle mental wellbeing. To follow the series and access all stories, tips and advice, visit our new Health section.

Originally published as Maria Ruberto details how to raise a resilient child

Read related topics:Can We Talk?