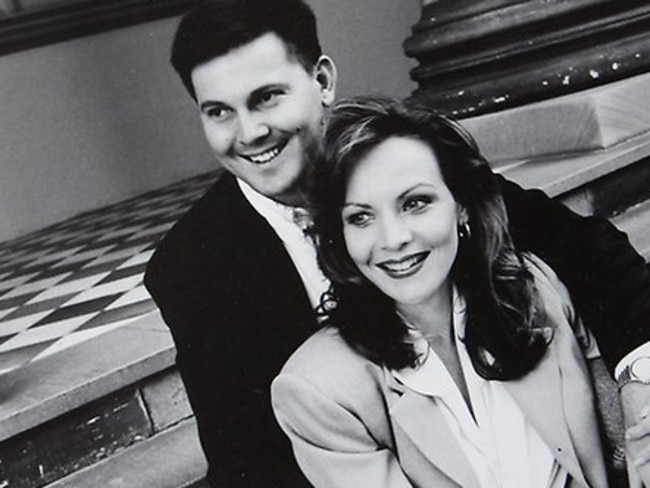

Jury finds Gerard Baden-Clay guilty of murdering his wife Allison

AFFAIRS, a sham marriage and two telling scratch marks. This is how the Baden-Clay murder trial unfolded.

GUILTY.

Cheers of “yes” went up from the victim’s family as a Supreme Court jury read its verdict today, while Gerard Baden-Clay bowed his head, jaw clenched, tears welling in his eyes.

The case has gripped the nation for weeks, but still so many questions remain.

Baden-Clay, 43, had pleaded not guilty to murdering his wife Allison, maintaining he didn’t know his wife had left their Brisbane home on April 19, 2012.

Allison’s body was found in a creek 13km away, some 10 days after her husband reported her missing. Baden-Clay’s legal team suggested she may have wandered off in a distressed state and fell — or jumped — into the creek.

The case was largely circumstantial and even the pathologist could not say for sure what killed Mrs Baden-Clay.

But the Crown said her death was no accident or suicide, but murder. And it pointed the finger squarely at her husband.

Baden-Clay, the Crown said, was having affairs and overwhelmed with financial problems and things came to a dramatic head on the evening of April 19 when Allison confronted him about his affairs.

She and his lover, Toni McHugh, were due to attend the same conference the next day — a meeting prosecutors labelled a “catastrophe” waiting to happen.

Ms McHugh admitted in court she “lost it” with Baden-Clay when she heard about the conference clash and pressured her lover about the future of their relationship.

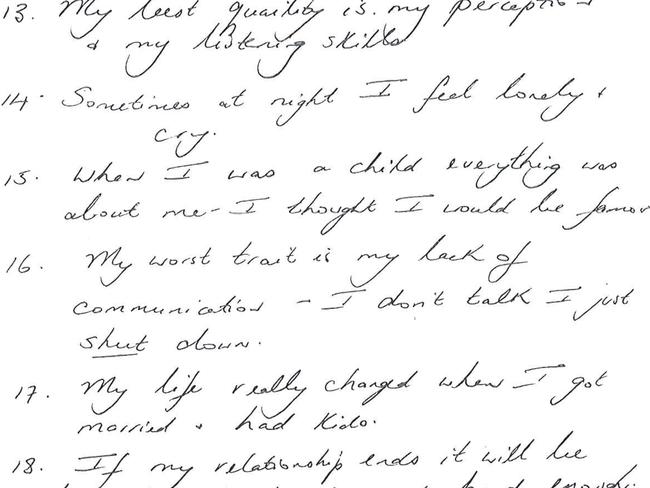

The trial heard intimate details of the couple’s marriage — from the fact they rarely had sex to their financial woes — and the counselling sessions they attended in an attempt to repair their marriage.

Justice John Byrne told Baden-Clay his financial circumstances were dire and his personal life was no better.

He said Allison remained tormented by the affair and questioned him about it the night she disappeared.

After he killed her, the judge said Baden-Clay took Allison’s body to the creek and threw her over the edge.

Later, he used a razor to cut himself near where Allison scratched him.

Justice Byrne said he stained Allison’s memory in exaggerating her depression — an act that was “reprehensible”.

In sentencing him to life in jail the judge said “the community action through the court denounces your lethal violence.”

The trial has gripped Australia over the past five weeks. Here are some of the key elements to the case.

THEIR MARRIAGE, HIS AFFAIRS, AND HIS LOVER’S FURY

Crown prosecutor Todd Fuller QC said on the surface they appeared a perfect couple. But it was all a “facade” and the reality was they were desperately unhappy people.

Mrs Baden-Clay had put on weight, become depressed and lost her sex drive — and her husband went looking for sex elsewhere.

After Baden-Clay told Allison he was having an affair with colleague Toni McHugh they went to marriage counselling.

He told his wife he wanted to be with her and not Ms McHugh.

But Ms McHugh was told the opposite — that he loved her “unconditionally” and set a date for when he would leave his wife for her.

The affair with Ms McHugh began in his real estate office in 2008 and continued on and off until Allison’s death even though he assured his wife it was over.

The trial heard Ms McHugh was furious that she was booked into the same conference as Allison was on April 20 — the day Mrs Baden-Clay was reported missing to police and hours after the Crown alleges she was murdered.

Both women would have been in the same room at together and Ms McHugh said she “lost it” in a phone call with Mr Baden-Clay.

She demanded he tell his wife of the clash and wanted to know what the future of their relationship was.

The court heard the meeting was a “catastrophe” waiting to happen and complicated Baden-Clay’s life even further.

Ms McHugh wasn’t his only lover though.

The trial heard he had multiple affairs with others without anyone knowing, something the Crown said proved he had the “bravado and confidence” to get away with killing his wife.

“The level of deception, it shows you what this man is capable of doing, his level of bravado and confidence in what he can carry out and carry off,” Mr Fuller said.

Baden-Clay told Relationships Australia counsellor Carmel Ritchie on April 16, 2012, — just days before Mrs Baden-Clay’s death — his wife did not trust him.

He had gone to the counselling session because Allison insisted and he wanted to “wipe the slate clean”.

THE MOTIVE, ACCORDING TO THE CROWN

Mr Fuller told the jury the wiping the slate clean comment was a telling one — and the act of killing Allison was triggered by her grilling Baden-Clay about his affair with Ms McHugh.

Although Allison had been under pressure and had mental health struggles, which she was taking medication for, those things were not factors in her death and did not cause her to wander off in the night, as suggested by Baden-Clay’s lawyers.

Mr Fuller: “This was a man having to deal with consequences of his own actions. Perhaps he felt he had no other choice. When a decision had to be made, that decision was made.”

BUT THE DEFENCE SAID NO MOTIVE TO KILL

Michael Byrne QC, on behalf of Baden-Clay, said he didn’t plan to leave his wife for Ms McHugh and did not kill her to be with the other woman.

He also rejected the suggestion he’d murdered her because he’d been under financial pressure.

Instead he put it to the jury that, despite the couple having had considerable difficulties, especially when he confessed to the affairs, there had been not even been “raised voices.”

There was no evidence he had a violent temper and the couple’s children didn’t hear any arguing the night their mother vanished.

APRIL 19, 2012 — TWO VERSIONS OF EVENTS

THE CROWN

The Crown said Allison’s death was “close, personal and violent”.

After what it says was Allison’s questions about his affairs, Mr Fuller said the couple struggled, and she “left her mark” on Baden-Clays face in the three visible scratches.

Those scratches were a crucial part of the Crown case. The accused said he did it shaving in a rush on the morning of April 20, 2012 with an old razor.

But forensic experts said the marks were more consistent with fingernail scratches.

The court also heard DNA belonging to another person was found under Mrs Baden-Clay’s left fingernails.

“Her left hand scratching the right side of his face,” Mr Fuller alleged.

“The scratches on his face show he was in close contact with his wife, that she was struggling.”

“It was close, it was personal, it was violent. What could have been in this man’s mind as he carried that out? His frustrations from his marriage? The double life? The risk to him of it all coming crashing down? Like he told Carmel Ritchie, he wanted to wipe the slate clean.”

The prosecutor said it was very unlikely Allison walked the 13 kilometres to where her body was found at Kholo Creek bridge.

He told jurors they could assume the body was dumped there and rejected suggestions she jumped or fell from the bridge.

“She was thrown down there.”

Six types of leaves found in Allison’s hair were also found at her home suggesting her head came into contact with the leaves at her house, maybe during the struggle or while she was unconscious and being dragged.

THE DEFENCE

Mr Byrne, the Barrister representing Baden-Clay, told the jury the accused never sought to conceal the marks on his face and rejected outright they were caused by Allison’s fingernails as she fought for her life.

Experts who assessed the injuries thought they were consistent with fingernail scratches, but equally they could not be certain they were not caused by a razor.

To explain how she got to the bridge, he instead raised the possibility her mental health issues could be a factor.

She had suffered bouts of depression and anxiety before and the court heard there was a “high chance” she was relapsing in April 2012.

On April 18 the Baden-Clays discussed his affair and then learned a relative was about to have a baby boy, something Mrs Baden-Clay had always wanted.

Mr Byrne asked the jury to think about whether these events prompted her to increase her medication.

That night he said they spoke again about the affair — and the “rawness” of the situation just “opened up”.

The defence case is there was no violent struggle at the house that night. No blood and no obvious signs of clean up.

Instead they raised the possibility that Mrs Baden-Clay, under medication, got disoriented on a walk, hallucinated and “ended up in the creek”.

Furthermore, the forensic pathologist who examined her was unable to establish the cause of death and could not say when she got a bruise on her ribs.

In fact, the barrister argued, the pathologist was unable to exclude falling into the water, drowning, or toxicity as possible causes of death.

There was also no mud in Baden-Clay’s car. This point was significant because the Crown version of events has Baden Clay stopping the car near the bridge and managing to get it through the grass before driving home and leaving it under the car port.