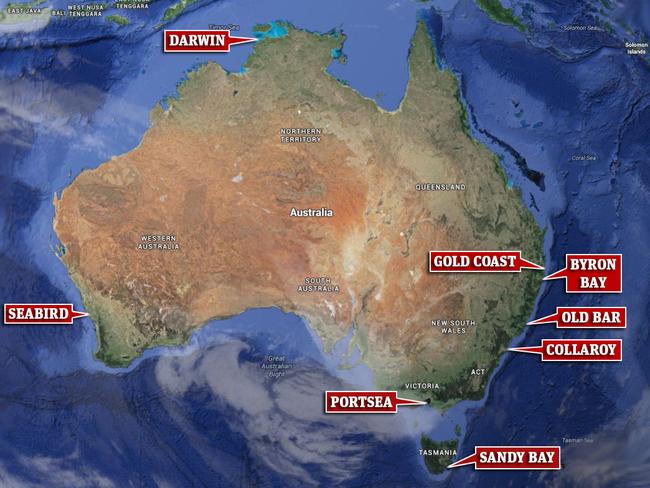

Is the Australian dream of a beachfront home really worth it?

SYDNEY homes are crumbling into the sea — but the same thing is happening along our vast coast. Is a beachside life really worth it?

IT’S the Australian dream — a multi-million-dollar beachfront house on a stretch of pristine coastline.

But as the nation watches millionaires’ row homes on Sydney’s northern beaches crumble into the ocean after wild weather belted Collaroy Beach, many are wondering if it’s a dream worth pursuing.

It’s not the first time houses have been swallowed by the sea, and with six per cent of the country living within 3km of the coastline and sea levels rising, it’s unlikely to be the last.

According to the latest report on climate change and coastal flooding by the Climate Council, houses were designed and built for a “stable climate”.

“But the climate system is no longer stable. Sea levels are rising and so are the risks,” the 2014 report warns.

It predicts more than $226 billion in commercial, industrial, road and rail, and residential assets around Australian coasts are potentially at risk by 2100.

But it’s the many beachfront homes around Australia already losing a decades-long battle to erosion that are on borrowed time before their Australian dream becomes a Collaroy nightmare.

Garry Egger lost the family beachfront home to the ocean 38 years ago, and says nothing has changed since then in terms of protection from erosion.

The Egger family home at Terrigal on the NSW Central Coast, and the house beside it, made international headlines in June 1978, when the sand dunes beneath them vanished and they were swallowed by the sea in the wake of a June storm.

Dr Egger says the “rich man’s rip” left the house vulnerable.

“The council approved an apartment block about three houses from us. When they were first hit by the erosion, council approved a rock wall in front. That made the ocean come around the side in what is now called a ‘rich man’s rip’,” says Dr Egger, who now lives “on a hill” in Manly.

He said rich man’s rips were perhaps the reason councils were reluctant to let locals go it alone when it comes to protecting millionaires’ rows of beachfront homes.

The loss of the Egger family home is often revisited when it comes to millionaires’ rows by the sea — not because the Eggers paid a lot for it (Dr Egger says it was bought in the 1950s by his schoolteacher father when it wasn’t common to live by the beach), but because it was one of the first cases of the sea swallowing a property built on sand dunes.

And also because Dr Egger sued Gosford Council for approving units and the sea wall.

The case dragged on for 10 years, ending in 1987.

“We won on the facts and lost on the law, which set up a precedent for councils in NSW dealing with this problem,” Dr Egger says of the case which canvassed how an emergency seawall built to protect the unit block further up the beach essentially directed the pounding surf towards the Egger home.

And 38 years on, as he’s watching the same happen at Collaroy.

“Then, as now, it was seen as an act of God, so even though you’ve paid insurance for 40 years as we had done you lose,” he says.

Despite his own experience, Dr Egger says councils should not be responsible for protecting private homes from the sea. And nor should citizens be allowed to erect their own protection.

“Once you’ve got rock down in front of a property you either have to put it all along the beach or not at all — it’s all or nothing,” he said.

“Almost four decades on we haven’t got much further than rich man’s rips — it’s a political problem when councils put money into building a wall to protect private property when people inland are screaming for money for facilities that can’t be paid for.

“In retrospect we should never have been allowed to build on the sand bank.

“The fact is you’ll never be able to legislate against, or build against or blame anyone for the power of the sea. You can’t sue, or legislate against Mother Nature.”

He believes the only solution is land buy backs or “planned retreats” but observes these are policies the land owners don’t seem keen on.

“They (private beachfront landowners) will spend a lot of time and energy and money trying to get their places protected but the fact is eventually many if not most of them will be encroached.”

QUEENSLAND

The Queensland Government spends millions annually trucking in sand to refill iconic Sunshine and Gold Coast beaches.

In 2013, Gold Coast beachfront property owners said the city council and State Government had abandoned them, and threatened a class action as severe erosion gouged away their properties.

Twice that year big swells and high tides after Cyclone Oswald stripped away millions of tonnes of sand from the Glitter Strip’s beaches, leaving homes teetering on the brink of cliffs and beach stairs and boardwalks collapsed into the ocean.

That erosion was described as the worst the Coast had seen in 40 years but locals say even more sand has since disappeared.

The Gold Coast is particularly exposed to sea-level rise, storms surges, flooding, beach erosion and the potential damage to infrastructure.

A 2009 study by the Climate Change Department estimated there were 2300 residential buildings located within 50m of sandy coast and 4750 within 110m. This exposes between 4000 and 8000 private dwellings to the impacts of coastal flooding, if sea levels were to rise by 1.1m.

In Southeast Queensland — without adaptation — a current 1-in-100 year coastal flooding event risks damage to residential buildings of around $1.1 billion, according to the Climate Council.

“With a 0.2 m rise in sea level, a similar flooding event would increase the damages to around $2 billion, and a 0.5 m rise in sea level would raise projected damages to $3.9 billion,” the report read.

WESTERN AUSTRALIA

Erosionsaw 15 beachfront houses once 20m from the sea teeter on a crumbling cliff in the coastal town of Seabird, just north of Lancelin and Guilderton, WA last year.

Residents campaigned for action for more than a decade after erosion began to threaten their homes in 2002.

The WA Government allocated $2 million to the shire earlier in 2015 to find a solution.

The residents will lose their beach, but keep their homes following a decision to build a seawall to stop erosion’s march.

In March, the council contracted engineering firm Neo Infrastructure to build a 500m long seawall as a medium-term solution at a cost of $1.8 million.

Seabird has had escalating erosion issues since 2002 but it is not the only coastal town affected by the issue in WA. Lancelin has also been at the centre of severe coastal recession.

Tens of thousands of dollars have been spent on sand to replenish the beach in recent years but the attempts only offer temporary relief, with the sand always disappearing back into the water.

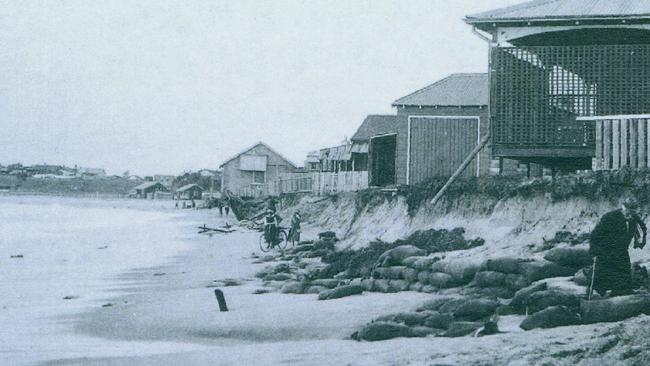

The councils of Albany, Busselton, Cockburn, Mandurah, Rockingham, Stirling, Wanneroo, Esperance, Manjimup, Geraldton and Bunbury on Perth’s western suburbs and the stretch from Guilderton to Jurien Bay were all battling coastal erosion. The sea has already claimed its share of buildings in WA — from Mandurah’s Ormsby Terrace in the 1980s to surf clubs at City Beach and Floreat in the 1950s and 1970s.

NEW SOUTH WALES

The seaside town of Old Bar near Taree is the most rapidly eroding and high risk piece of coast, losing an average metre seafront a year, far outstripping other areas in terms of property at risk.

Several residents have already lost their homes to the sea and scores more at risk. Roaring seas have ploughed through more than 40m of foredune in just 12 years.

In 2012, Old Bar property values dived along a once exclusive cul-de-sac, with homes once worth $1.5 million or $2 million, later abandoned because of erosion and offered for $300,000.

NSW has a long history of beachfront houses and towns being affected by coastal recession.

In 1974, Cyclone Pam caused beach erosion so severe that the whole of Sheltering Palms Village, in the Byron Bay shire, was destroyed.

Byron Bay’s Belongil Beach has long been the site of heated debate, with council, developers landowners and green groups engaged in a bitter battle over a sea wall proposal there.

A 100m rock wall was built last year at Belongil at a cost of $900,000 to the council and $300,000 to private landowners — and critics are fighting its extension to 1km.

The NSW Government still considers Byron Bay and Warringah shires two of its worst erosion hot spots, along with the shires of Ballina, Clarence Valley, Port Macquarie-Hastings, Greater Taree, Great Lakes, Wyong, Gosford, Pittwater and Eurobodalla.

NORTHERN TERRITORY

Coastlinesin Darwin have eroded an average 30cm a year for the past three decades.

This year, Darwin Council started building a seawall along Nightcliff foreshore, one of the city’s most affluent waterfront suburbs, as the first major Coastal Erosion Management Plan project.

A 155m seawall was built along the perimeter of Sunset Park to manage ongoing erosion and limit damage from storm waves overtopping.

In 2013, the council identified Darwin’s most vulnerable coastal erosion sites with some of the city’s most popular sunset strips — East Point and Mindil Beach — were also identified as vulnerable to erosion.

TASMANIA

Exclusivewaterfront properties in Sandy Bay worth millions are at risk from rising sea levels and may have to be abandoned or demolished, a 2015 report says.

The report commissioned by Hobart City Council identified 38 properties at Nutgrove Beach, Long Beach, Sandy Bay Point and Blinking Billy Point worth a combined $40 million most at risk.

It said some homes may need to be removed in coming decades as dunes retreat up to 50m from the present high water mark. The report also raised the possibility of floating or removable homes. Among the possible solutions was a “planned retreat” with further development banned, and properties abandoned or demolished as sea levels rise.

Rising sea levels and the increased risk posed by storms could lead to council refusing development applications or subdivisions. The report said by 2050 the number of properties at risk could rise to 114; by 2100, some 176 properties may be at risk of erosion and inundation.

VICTORIA

The luxurious holiday destination of Portsea sees beach houses typically sell for millions, but the beach has now dissolved completely. Sandbags protect the buildings from the same fate.

Erosion at several Mornington Peninsula beaches has long had residents fearing for the future of their Port Phillip Bay foreshores.

A report released by Western Port Greenhouse Alliance in June 2008 warned of rising sea levels, coastal erosion and flooding as impacts of climate change.

Peninsula beaches likely to be most affected included West Rosebud, Dromana Shoreham, Frankston, Balnarring and Safety Beach.

Another 2013 report by environmental firm Water Technology indicated the severe erosion that has devastated Portsea Front Beach was likely caused by bay dredging.

Many of Port Phillip Bay’s beaches are no longer natural, regularly reconstructed with carted-in sand.

A $10 million fund to fix coastal foreshores around Port Phillip Bay will be established using money from the Port of Melbourne lease, according to the State Government.

The funding will be restricted to “bay-based and neighbouring bay-catchment areas” and recipients will have to match funding dollar for dollar, either in cash or in-kind.

SOUTH AUSTRALIA

The State government has been managing Adelaide’s beaches for more than 30 years to stop sand eroding and moving north along the coast. Sand has been carted in on trucks to replenish the southern and central beaches affected by erosion.

“Without this intervention, several of Adelaide’s southern metropolitan beaches would have very little sand left on them and foreshore properties would have been damaged by storms,” the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources states on its website.