Federal election 2019: Political opinion polls show themselves to be deeply flawed, inaccurate

They’ve brought down prime ministers, but how much faith can be placed in opinion polls after the 2019 federal election?

The thing that largely led to several prime ministers being knifed by their own parties has shown itself to be a deeply flawed measure.

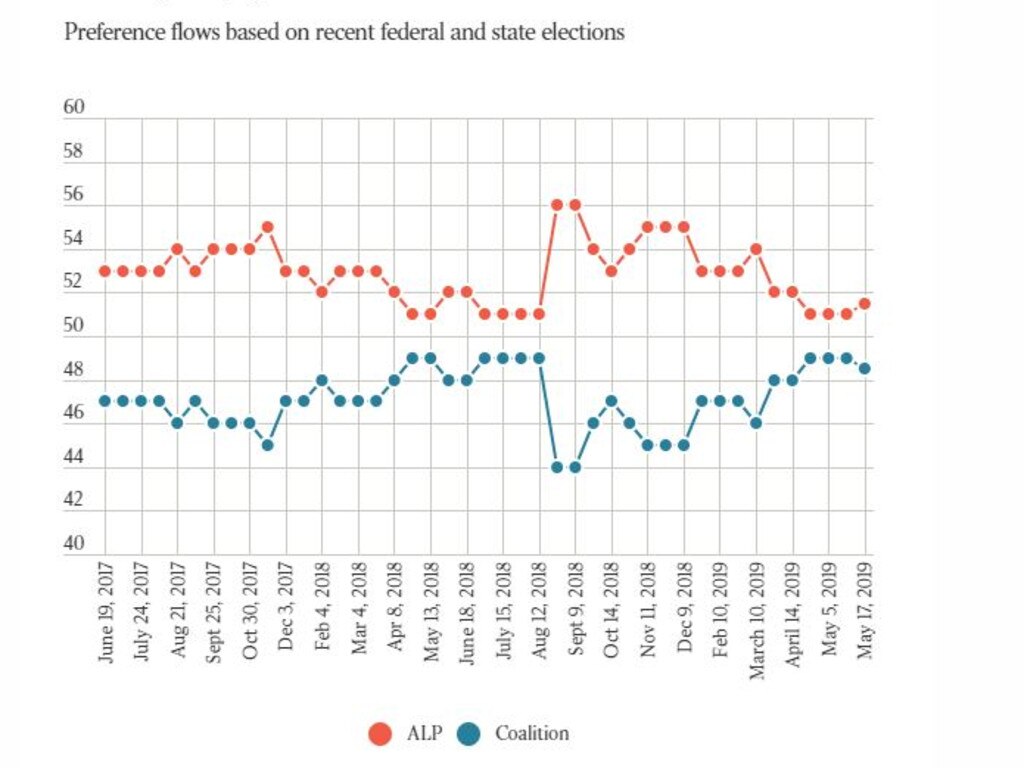

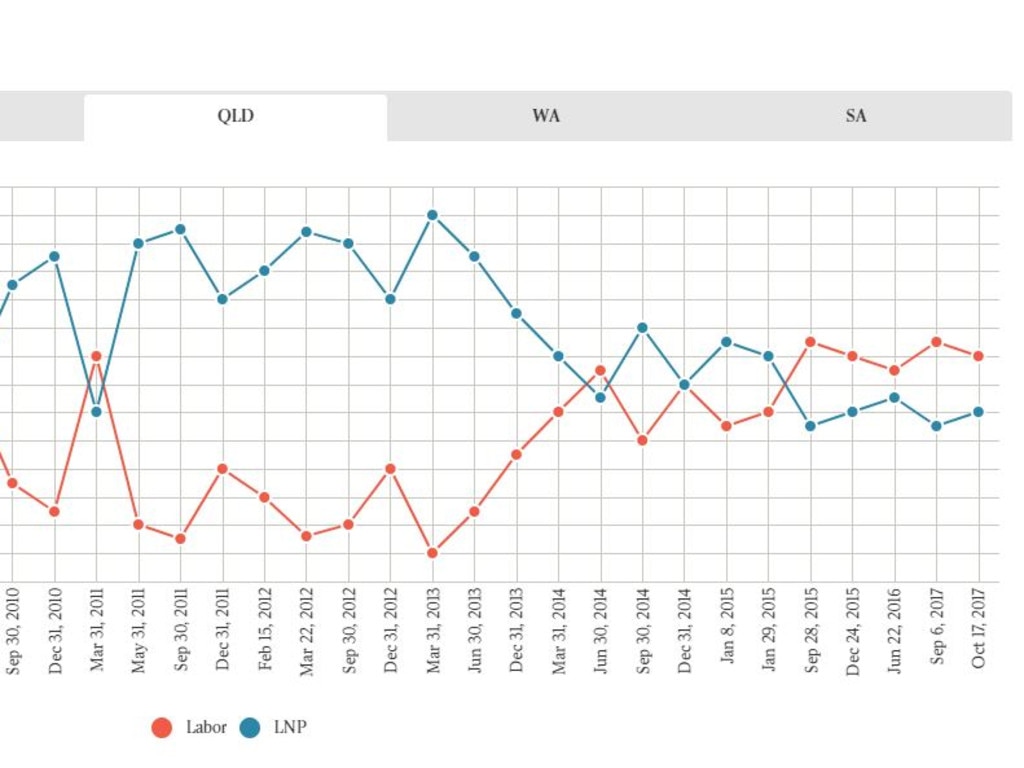

Successive opinion polls over the past three years pointed to a convincing Labor victory at Saturday’s federal election.

It also showed incredibly tight contests in a number of seats.

But as we now know, Bill Shorten is not the PM and the Coalition has hung on to power against all expectations.

So, why did Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull lose their jobs based on the pulse of the nation that could’ve very well been misread the whole time?

Newspoll, considered one of the most reliable indicators of political fortunes, was cited by Labor and the Liberals during their respective periods of leadership chaos.

But it was way off on both a primary vote and two-party preferred basis on Saturday.

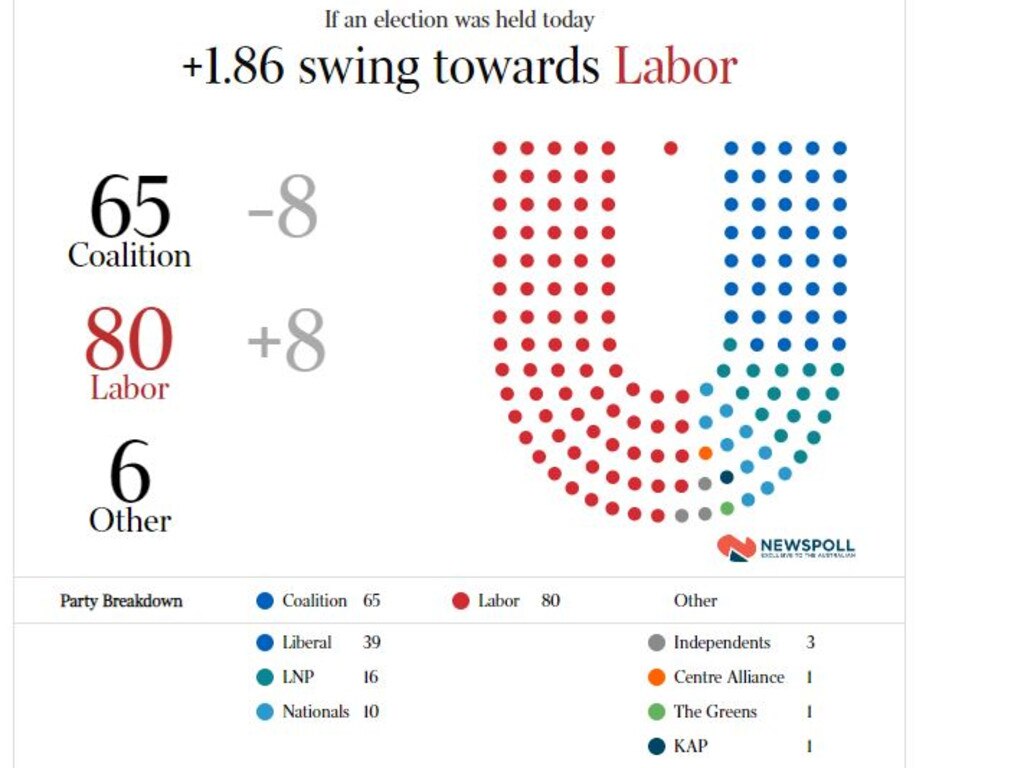

The final Newspoll of the campaign forecast a 1.8 per cent swing towards Labor, with the Opposition picking up 80 seats and the Coalition scoring 65.

On the current count, the Coalition has won 75 seats and Labor 67, with a swing of just over 1 per cent to the Government.

RELATED: How it all fell apart for Labor and Bill Shorten

Similarly, polling conducted by YouGov in a swag of key seats was woefully wrong in more instances than it was right.

Ipsos exit polling conducted on Saturday was blasted across Channel 9 screens and throughout its newspaper and website network, declaring a Labor victory.

And all of the polling failed to read the level of support for Pauline Hanson’s One Nation.

Political commentators and pundits, perhaps in a bid to wipe some of the eggs from their own faces, have questioned how the pollsters could’ve gotten it so wrong.

RELATED: Seat by seat — how your electorate voted

Much less emphasis should be placed on polls, the ABC’s Annabel Crabb declared late on election night, and parties should stop toppling their leaders based on them.

Sky News reporter Laura Jayes said they should only be conducted a few times annually outside of an election year, given how regularly they distract from the real conversation.

In the coming days and weeks, scrutiny of pollsters is bound to grow, with some very legitimate questions to be answered.

Australia is not alone. Polling caused significant upsets in the United States and Britain too.

In the presidential election, Hillary Clinton was consecutively polling ahead of Donald Trump, making his win totally unexpected.

And the Remain camp was winning the polls in the lead-up to Brexit.

It’s clear traditional methods of polling are flawed and need examination, particularly given how much importance is placed on them in Australian politics.

Academics abroad have examined what’s wrong with polls and made a couple of fascinating observations.

Research published in Nature Human Behaviour from the Santa Fe Institute and Max Plan Institute found asking about a person’s voting intentions, or who they expect will win, can lead to inaccurate results.

“Asking people if and how their social circle intended to vote was a more accurate predictor of the outcome than when participants only provided their own intentions or their prediction of who would win,” the British Psychological Society reported.

“In fact, in one poll, the researchers found that the social circle question was almost twice as accurate as reporting one’s own intentions (82 per cent vs. 46 per cent) in the five key swing states that lost Clinton the election.

“Asking about participants’ social circles means they don’t have to reveal their own potentially embarrassing preferences, and it indirectly increases the sample size of the poll itself.”

Polling has wielded enormous influence in Canberra for a long time — an establishment now wondering if that dominance should continue.