The secret behind the Christmas society murder scene frozen in time

THE secret behind the murder of a cricket star by his alleged lover in 1920 had its beginnings in an attack by a lunatic seven years earlier.

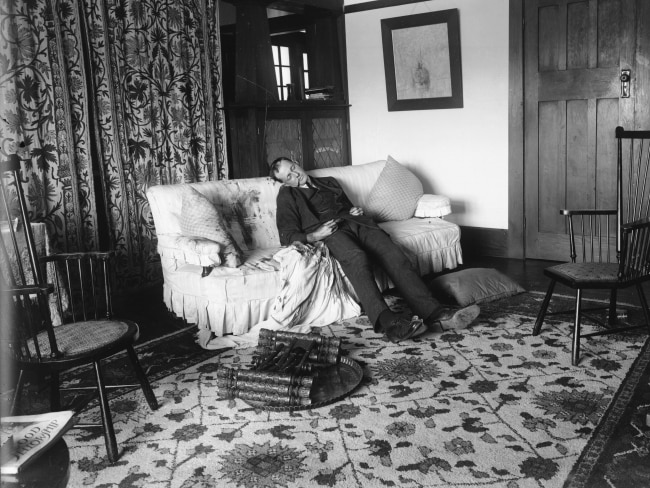

THE murder scene is confronting, unforgettable and frozen in time.

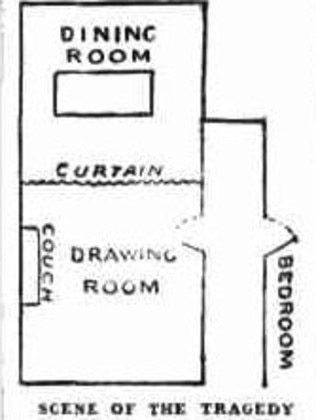

The dead war hero and cricketing star is sitting quite upright for a man who has been shot through the head and heart on the couch of his lover’s stylish drawing room.

By the time the police photographer captures the scene inside the house of one of Sydney’s establishment families, 30-year-old Dr Claude Tozer has been lying there for almost a day.

Gory forensic reports of exactly where the bullets tore through the tall, handsome GP’s body are being printed in news reports which have transfixed the nation just days before Christmas.

The public is both horrified and fascinated.

Already the flags at Sydney Cricket Ground, where he was due to captain NSW against Queensland 10 days later, are flying at half mast.

Hidden beneath the couch is as half-written prescription. Embedded in it are three bullets.

In a bedroom of the same Lindfield house on Sydney’s North Shore lies the woman who shot Tozer.

Dorothy Mort, an aspiring motion picture star, lies in “a dangerous condition” with a self-inflicted wound to her chest and having taken laudanum.

The 32-year-old, who has two young children, is the wife of Harold Sutcliffe Mort, of the wealthy TS Mort family of industrialists, pastoralists and churchmen.

As an outpouring of grief over Dr Tozer grips Sydney in the days over Christmas 1920 and into the New Year, Dorothy Mort will be described as “beautiful, respected and admired”.

CID detectives arriving at her house will discover a cache of explosive letters written by Mrs Mort.

But she also has another, more terrible secret.

She manages to keep it even as she is charged with murder and taken off to Long Bay Penitentiary, where she will live like a grand dame with an indigenous inmate as her servant.

But for the moment, the detectives are still piecing together what led to the scene in the drawing room.

On the morning of Tuesday, December 21, 1920, Harold Sutcliffe Mort telephoned Claude Tozer about his wife Dorothy, who had been in bed for four days.

The 30-year-old doctor, who was single, had been treating Mrs Mort since July for nerves and hysteria.

As the cache of letters would reveal, a love affair had developed between doctor and patient, but Tozer had decided he should get married and had proposed to another woman.

Mrs Mort had decided that if she could not have the doctor, then no other woman would.

She had also spoken to her servant Florence Fizelle about suicide, and that her father had himself committed suicide.

On that fateful Tuesday, Ms Fizelle said Mrs Mort “seemed to be out of her mind”.

Around 11.30am, 10 minutes after Dr Tozer arrived at the Lindfield house and was admitted into the drawing room, Ms Fizelle heard a gun shot.

When she called through the door, Mrs Mort said everything was all right.

Ms Fizelle heard two more gunshots and Mrs Mort retired to her bedroom, asking twice for iced water.

The Mort’s children, Virginia, 8, and Maurice, 6, returned home from school and by 7pm, Ms Fizelle managed to force her way into Mrs Mort’s bedroom.

She found her employer covered in blood, with a chest wound and under the influence of a narcotic.

Ms Fizelle called a doctor and the police, who found Tozer dead in the drawing room.

He had been shot in the back of the head, in the temple and in the chest — a bullet would be found lodged in the roof of his nose.

His head wounds were adjacent to the scars he bore from on the Western Front in France, where in 1915 a piece of shrapnel passed into the right temporal lobe of his brain, lodging under the skull.

His vest had been rebuttoned over the chest wound, and a Colt pistol was in his lap.

At 9pm on December 23, Mrs Mort was removed by ambulance to Royal North Shore Hospital and placed under police guard.

The next day, cricketers, doctors and family attended a large funeral at Waverley Cemetery.

Claude Tozer was remembered for his brilliance as a batsman, his promise as a test cricketer, and his bravery in World War I.

Tozer served as a medical officer at Gallipoli in the same unit as Simpson, of donkey fame, He served at Pozieres in France, where he was hit by a shell, and in Belgium where he earned a Distinguished Service Order.

It is unlikely he could have survived the shots fired by Dorothy Mort.

It later emerged in court that after shooting him three times, she lay in his arms for two hours afterwards as Ms Frizelle fretted outside the door.

Mrs Mort had told a friend before the shooting that she was pregnant to Dr Tozer and that she was going to marry his brother (he didn’t have one) and travel overseas.

She eventually told police she had been immediately besotted when Dr Tozer made his first house call to treat her.

“I loved him immediately,” she said. “He was so handsome and big and splendid that I thought how wonderful a son would be of his.”

In letters found by detectives which had been written by Mr Tozer, he had told Mrs Mort who he called “Dearest Lady” and “Lady Diana” that she had so stirred him he was now “a sleeping volcano”.

In March 1921, Dorothy Mort went on trial for Dr Tozer’s murder at Sydney’s Central Criminal Court in Liverpool St.

Her defence counsel was angling for a finding of not guilty by way of insanity.

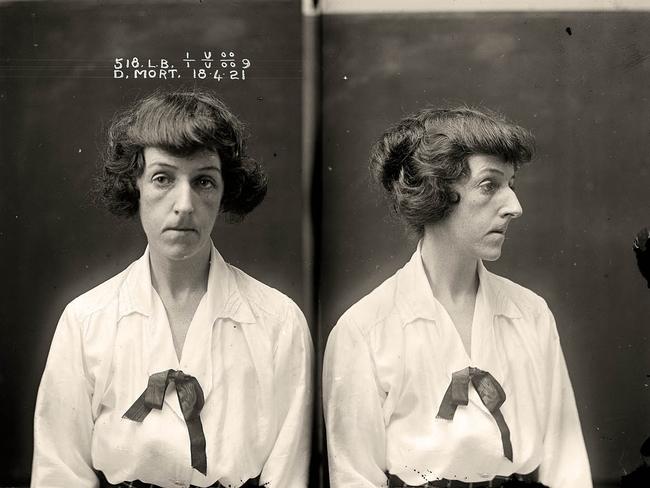

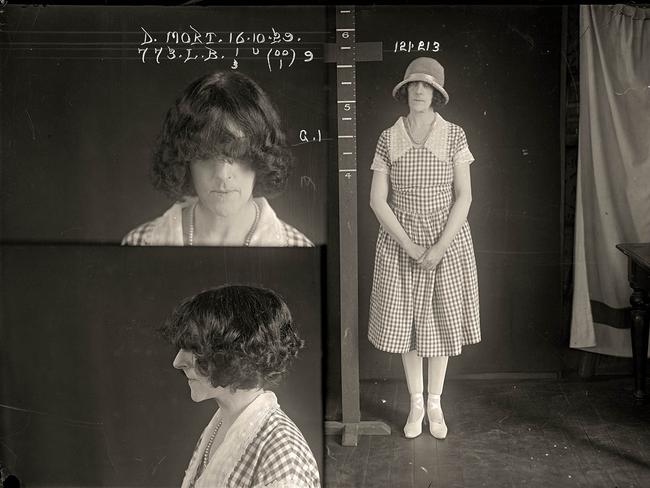

Led into court by a gaol matron, Mrs Mort wore a thick veil which was lifted to reveal a pale narrow face.

A surging crowd poured into the public gallery of the courtroom filling every seat.

It was then that Mrs Mort’s secret was revealed, when her husband was called to the stand and told of a “remarkable coincidence”.

Mr H.S Mort, an engineer, church warden and avid stamp collector, said his wife was very hysterical.

He said that she spoke of death frequently, had dreams about her children being burned, and other nightmares of an unbalanced mind.

Asked what the background to this was, Mr Mort revealed that he feared his wife had a hereditary insanity and that every December, on the anniversary of her father’s death she became affected.

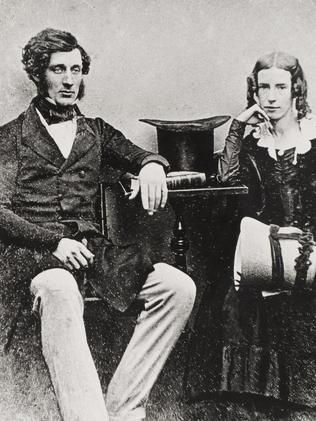

He had married his wife, Dorothy Woodruff, in 1909, and four years later an incident had happened which had certified that his wife’s father was insane.

Mrs Mort’s father had been a well-known city businessman and fire insurance adjuster, William Mackay Woodruff.

On September 22, 1913, Woodruff had, “apparently in a fit of madness” attacked his wife and son with an axe, breaking their skulls. He then attempted to commit suicide.

Ronald Woodruff, 26, later told police how he had fended off his father, who then severely wounded his mother and both had narrowly survived the attack.

Afterwards, he had found his father lying “quite nude” on the lawn having attempted to cut his own throat and “raving wildly about trains”.

The 55-year-old was charged with feloniously wounding his wife Helen with attempt to murder, found not guilty on grounds of insanity and detained with the Governor’s pleasure.

After years in Goulburn prison’s insane wing, Woodruff was released and went to New Zealand, where on December 9, 1919 he killed himself.

A gunsmith told the court that Dorothy Mort had bought a Colt revolver from him five days before the tragedy, saying she wanted it as a present for her husband in India.

He had instructed her how to use it.

On April 18, 1921 Dorothy Mort was acquitted on the grounds of insanity, but nevertheless remained imprisoned in Long Bay Gaol at the Governor’s pleasure.

There she remained for nine years as various supporters, including her husband, tried to secure her release.

One female parolee told a newspaper Mort “held herself very aloof from the others. She was spoken of by the others as a very educated person ... I heard that she is very delicate”.

In 1926, a report headlined “Belle of the Gaol” was published calling Mort a “star boarder” of Long Bay.

It said the killer spent her time in “genteel seclusion”, sewing and reading romantic novels featuring dashing lovers.

She favoured works by Charles Garvice, a prolific author of romantic potboilers featuring missing treasures, lost heiresses and heroes from titled families.

Mort was said to gush to other women inmates: “The hero in this book is absolutely thrilling.”

She lived not in a cell, but in a screened-off corner of Long Bay prison hospital with a carpet and the general demeanour of a small bedroom.

Her husband paid for fresh flowers and fashionable clothes which she was allowed to wear instead of a prison uniform.

The reports said, “the ordinary prisoners, who have killed nobody, she shuns with aversion, even refusing to sit near them when she enters the hall dressed up for gaol concerts.

“She prefers the association of the inebriates, who are not classed as prisoners.”

Mort wore diamond jewellery and had a baker and a butcher on call, paid by her husband, and was allowed to leave prison on occasion.

In addition, she had a woman named Bella Carr as her servant.

On October 16, 1929, Dorothy Mort was released.

Dressed in a gingham dress with a lace collar, pearls, stockings and high heeled shoes with ankle ribbons, she removed her hat for a mug shot, her eyes obscured by her hair.

On the outside, Mort returned to her family, with her daughter now 17 and her son 14.

H.S Mort died in 1950. Dorothy lived on until 1966, dying at the age of 81.

- This story was first published by news.com.au in December 2017